Alfond Collection: Artists S-V

From Matt Saunders to Charline von Heyl, explore the works of artists S-V in the Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art.

PLEASE NOTE: Not all works in the Rollins Museum collection are on view at any given time. View our Exhibitions page to see what's on view now. If you have questions about a specific work, please call 407-646-2526 prior to visiting.

Artists Featured in This Section

Analia Saban

(Argentine-American, b. 1980)Woven Angle Gradient as Weft, Cadmium Yellow Medium, 2021

Woven acrylic paint and linen thread on panel

70 ¼ x 70 ¼ in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2021.1.8. Image courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles

Born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Analia Saban works across the mediums of painting, drawing, weaving, and sculpture to challenge viewers’ expectations of what constitutes a work of art. In so doing, she creates new hybrid forms that expand traditional notions of artmaking, simultaneously playing on art historical references, including the history of minimalism, while experimenting with new techniques and technologies. One of Saban’s unconventional methods is to weave “threads” of dried acrylic paint through linen, producing works in which paint and canvas are physically intertwined. The series Woven Angle Gradient as Weft, comprised of six paintings that focus on a primary or secondary color gradient, investigates the relationship between the analog and the digital. The compositions are inspired by image-editing software and suggest the stilled hands of a stopped clock, inviting the viewer to pause and reflect on notions of time and duration. Saban lives and works in Los Angeles.

Sebastião Salgado

(Brazilian, b. 1944)Greater Burhan Oil Field, Kuwait (Capping a wellhead), 1991

Gelatin silver print

20 x 24 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2021.1.20 © Sebastião Salgado

Sebastião Salgado

(Brazilian, b. 1944)Kabul, Afghanistan (people among ruins), 1996

Gelatin silver print

20 x 24 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2021.1.21 © Sebastião Salgado

Sebastião Salgado

(Brazilian, b. 1944)Serra Pelada, Brazil (St. Sebastian), 1986

Gelatin silver print

20 x 24 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2021.1.22 © Sebastião Salgado

Sebastião Salgado

(Brazilian, b. 1944)The beach of Vung Tau, Vietnam, 1995

Gelatin silver print

20 x 24 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2021.1.23 © Sebastião Salgado

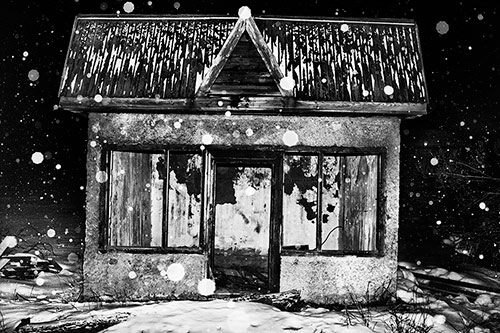

Mohammed Sami

(Iraqi, b. 1984)Weeping Walls, 2022

Mixed media on linen

110 ¼ x 137 ¾ in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2022.2.22 Courtesy Stuart Shave/Modern Art, London. Copyright the Artist. Photo: Ben Westoby

Born in Baghdad, Iraq, in 1984, Mohammed Sami immigrated to Sweden as a refugee in 2007. His evocative paintings are characterized by the representation of interior spaces devoid of figures. Grounded in the artist's personal experiences, his images explore the intersections of memory and identity, and foreground ideas about the past and the future. These settings convey a sense of loss emphasized by familiar objects left behind and the traces of human presence evident in the space. In this painting, the hanging wires of a light fixture at the top center of the composition, and the faded wallpaper around wall furnishings and decorations emphasize the emptiness of a place that contains within it the memories and stories of those who once inhabited it. Mysterious and powerful, Sami's environments speak to what we leave behind. Sami currently lives and works in London.

Tomás Saraceno

(Argentinian, b. 1973)Cloud Cities-Nebulous Thresholds, 2017

Metal, polyester rope, fishing line, iridescent plexiglass, metal wire, steel thread

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2017.6.46. Image courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York.

Tomás Saraceno was born in Argentina in 1973, and currently lives and works in Berlin. The artist’s trademark floating sculptures and installations explore the relationship between time and space, finding new ways to unite the fields of art and science. Saraceno draws inspiration from the natural sciences, astrophysics, and architecture to create his innovative and imaginative sculptures and installations. His training in architecture and his studies in the international Space Studies Program at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley inform his practice and his approach to the built environment.

This installation is part of the artist’s Cloud Cities series, inspired by his two-decade-long research investigation of urbanism and environmental utopias. It embodies his notion of futuristic habitats: each module represents an inhabitable structure that floats freely throughout the atmosphere.

The piece draws from his analysis of modern architecture of the 1960s and 1970s while representing the idea of futuristic aerial living. It was created with a variety of utilitarian materials, including rope, fishing line, and Plexiglas to integrate both his artistic and habitable ideas. As the viewer moves under the work, the installation itself appears ever-changing, the metal, ropes and wire within the modules appearing different from every angle.

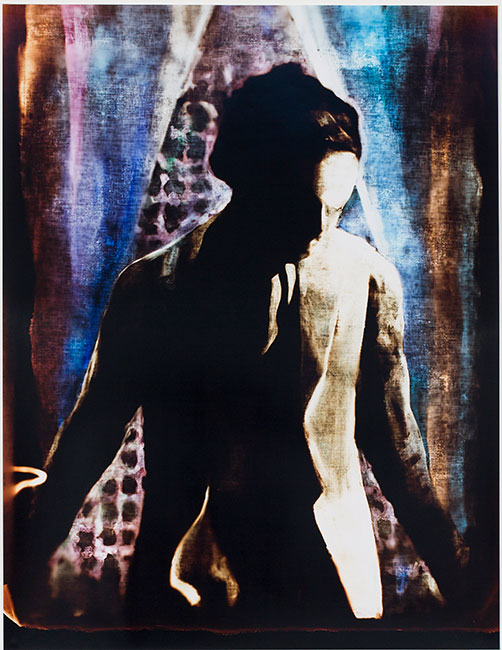

Matt Saunders

(American, b. 1975)Borneo (Rose Hobert) #5, Version 2, 2013

55 x 44 21/64 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.153. © Matt Saunders. Image courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

Hybridity, appropriation, transformation, and narration underpin Matt Saunders’s practice. Engaging the histories and techniques of film, photography, and painting, Saunders creates large-format two-dimensional works, as well as animations, films, and installations that intentionally merge mechanical and hand-produced images and processes in a material-driven conceptualism.

In Borneo (Rose Hobart) #5, Version 2, Saunders portrays Depression-era actress Rose Hobart in a still from East of Borneo (1931). The B movie gained cult status from Joseph Cornell’s surrealist 1936 edit. Saunders co-opts this frame in a characteristic gesture that pulls obscure cinematic history into the realm of portrait painting. He uses the complex technique of creating a hand-painted, colorized negative from a black-and-white film still, which he then develops on photosensitive paper. The resulting image is necessarily inverted and a photographic print of what is essentially a painting—capturing every minute gesture of Saunders’s brush.

Here, Hobart is parting a curtain, as if she just appeared on the scene. While providing compositional drama, the curtain emphasizes Saunders’s painterly technique in diaphanous veils of inky blues, purples, and umbers. Color has only recently become an active component of the artist’s work and its presence, as in Cornell’s appropriation of East of Borneo or the first color movies such as Gone With the Wind (1929), has a somewhat surreal effect, as if the color were not necessarily descriptive of a thing or place but of an idea. In selecting this fragment of found imagery for his ode to Hobart, Saunders is front-loading a theatrical moment, and this triggers viewers’ own vaults of memories so that they may project their own versions of what has just passed or is about to happen.

As at the end of a film when credits give way to the momentary flickering of the end-pieces of a filmstrip, Saunders exposes the edges of his painterly negatives. We see bent corners of fabric and the irregular edges of the material as it is captured on the paper. The effect of this gesture, at once painterly and conceptual, reminds viewers that they occupy a constructed space and points to the ephemerality of the artist’s reconstructed scenes and the subjects he chooses to reanimate.

In 2013, Saunders reflected on how his photographs have become “more animated and liquid… in a medium between media.” His photographs are fleeting ciphers, fugitive expressions of imagined spaces and the in-between; and in a world of so much digital creation and manipulation, Saunders’s process is anti-mechanical, driven by the connection between the eye, the hand, and the beating heart.

--Abigail Ross Goodman

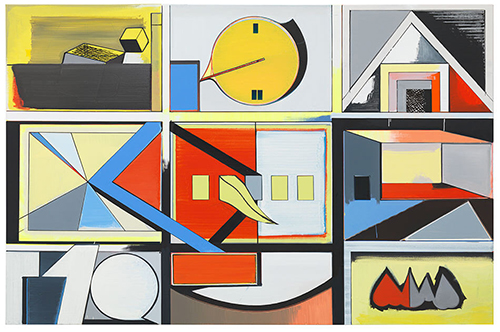

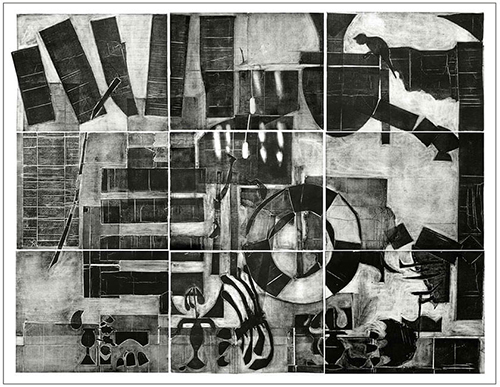

Thomas Scheibetz

(German, b. 1968)A Panoramic VIEW of Basic Events, 2011

Oil, vinyl, lacquer, pigment marker, and spray paint on canvas

74 3/4 x 114 1/8 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.152. © Thomas Scheibitz. VG BILD-KUNST, BONN 2015. Image courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York.

At first glance, Thomas Scheibitz’s paintings appear to be happy concoctions of comic abstraction with inflections of the neo-classical surrealist paintings of Giorgio de Chirico and hints of El Greco’s painterly drama. A synthesized blend of abstraction and realism that generates geometrically determined space and gestures towards platonic forms, Scheibitz’s paintings are deeply conceptual propositions that address notions of linguistic structure as it pertains to an increasingly imaged-based society. The artist uses a self-described bifurcated “studio system” split between his sculpture and painting. While differing in process, both sides use an aggregate of shapes in a range of colors and combinations from a growing lexicon of abstract forms of the artist’s making. This vocabulary is indirectly generated by Scheibitz’s ongoing image archive—itself an amalgamation sourced from popular media and imagery with a particular interest in graphics. Isolated and modified letters routinely appear alongside basic forms to argue that it is not in the single term or element but in the combination of elements—be they letters, symbols, words, or ideas—where meaning lies. In all, Scheibitz presents the structure of painting—in line, color, form, etc.—as an endless resource by which to process the world around us, and vice versa.

In A Panoramic VIEW of Basic Events (2011), Scheibitz uses a nine-panel grid and title to evoke a dramatic narrative arc in an abstract storyboard. The geometry moves between utter flatness, shallow shading, and three-dimensional rendering in a way that adheres to the push-pull of modernist abstraction, yet with the undertone of comic sensibilities in speech bubbles and frames. Like a filmic storyboard, Scheibitz’s Panoramic VIEW moves in and out of space in a further play of contrasts between detailed close-ups and pulled-back “shots.” In doing so, the painting blurs any sense between details, fragments, and full compositions.

--Dina Deitsch

Thomas Schiebitz

(German, b. 1968)Georgette und Landschaft, 2013

Oil, vinyl, pigment marker, and varnish on canvas

94 1/2 x 106 1/4 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.151. © Thomas Scheibitz. VG BILD-KUNST, BONN 2015. Image courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York.

The artist’s Georgette und Landschaft merges portrait and landscape genres in a compressed and fragmented space as Scheibitz continues both to dismantle and to build up the case for painting today. Here each mark and gesture is a deliberate play off another—a lyrical line, a brushy expanse, and architectonic form—to create a scene of mystery and drama. In both paintings, Scheibitz uses a spare but jarring palette and reductive forms to present limitless possibilities for abstraction.

--Dina Deitsch

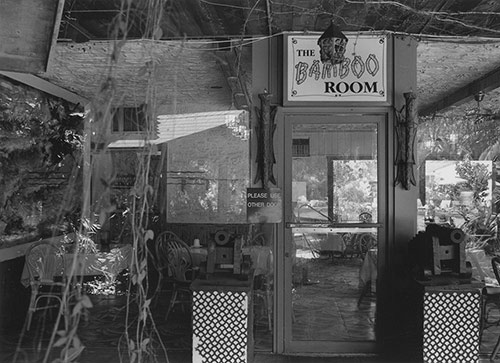

Peter Schreyer

Bamboo Room, Langford Hotel, Winter Park, Florida, 2000

Gelatin silver print

17 1/4 x 21 1/8 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2015.1.24. © Peter Schreyer.

Peter Schreyer

College Park Publix Supermarket, Orlando, Florida, 1991

17 1/4 x 21 1/8 in.

Gelatin silver print

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2015.1.21. © Peter Schreyer.

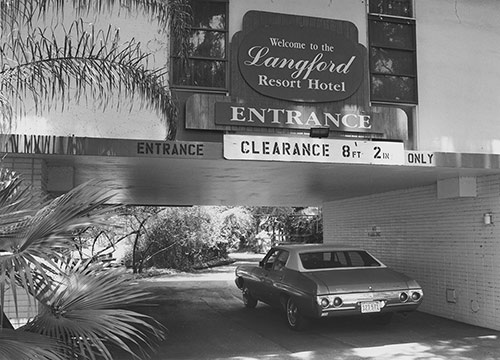

Peter Schreyer

Entrance, Langford Hotel, Winter Park, Florida, 2000

Gelatin silver print

17 1/4 x 21 1/8 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2015.1.22. © Peter Schreyer.

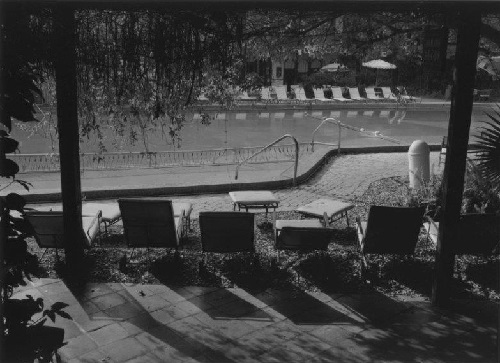

Peter Schreyer

Swimming Pool at Night, Langford Hotel, Winter Park, Florida, 2000

Gelatin silver print

17 1/4 x 21 1/8 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2015.1.23. © Peter Schreyer

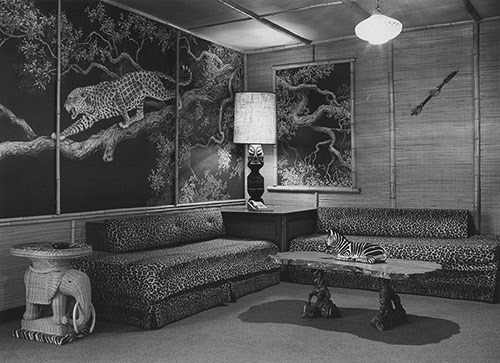

Peter Schreyer

Safari Room, Langford Hotel, Winter Park, Florida, 2000

Gelatin silver print

17 1/4 x 21 1/8 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2015.1.25. © Peter Schreyer.

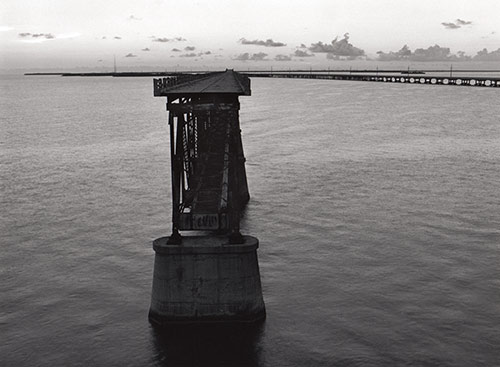

Peter Schreyer

Seven Mile Bridge at Dusk, Bahia Honda, Florida, 2004

Gelatin silver print

17 1/4 x 21 1/8 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2015.1.20. © Peter Schreyer.

Peter Schreyer

Southernmost Point, Key West, Florida, 1994

Gelatin silver print

17 1/4 x 21 1/8 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2015.1.19. © Peter Schreyer.

Hadieh Shafie

(Iranian-American, b. 1969)White, Turquoise, Green, Gold, Yellow & Blue, 2012

Ink, acrylic, and paper with printed and hand-written Farsi text Esheghe (love)

36 x 36 x 3 1/2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.74. Image courtesy of the artist and Leila Heller Gallery, New York.

Repetition. Process. Time. These are the three qualities that Iranian-American artist Hadieh Shafie identifies as constants in her work, and they are all visible in her meticulously crafted painting White, Turquoise, Green, Gold, Yellow, and Blue (2012). Shafie’s painstaking process begins with hand-coloring strips of paper and inscribing the length of each with a single word written again and again like a mantra: esheghe, the Farsi word for love. She then rolls the paper into hundreds of tiny individual scrolls, which are subsequently arranged to form a larger composition.

Just as Shafie’s prismatic paintings are composed of thousands of layers of tightly wound paper, they also carry multiple levels of meaning. On one level, her work brings together several strands of Persian culture. Her accumulations of circular discs resemble Middle Eastern tilework, an effect that is enhanced by her chosen palette in White, Turquoise, Green, Gold, Yellow, and Blue. She acknowledges her heritage even more directly in her use of Farsi script. Since Islamic calligraphy is writing in the service of God, Shafie’s spirituality is a vital part of her creative process as well as her finished product. By winding the paper, however, she nearly obscures the text, and once the piece is completed it can only be glimpsed upon close examination. This gesture raises larger questions of accessibility and translation across cultures, yet given the text the artist has chosen, speaks to the undeniable universality of love.

On another level, Shafie’s compositions resonate with multiple moments in the history of abstraction as it developed in Europe and America. The gestural nature of calligraphy is analogous to the Abstract Expressionists’ mark-making, which Shafie cites as a specific source of inspiration. Her vibrant palette also bears a resemblance to the saturated hues favored by the Washington Color School. These psychedelic shades and their geometric patterning find yet another parallel in the visual effects of 1960s Op Art. The different colors identified in the title of White, Turquoise, Green, Gold, Yellow, and Blue recede and advance based on their temperature, generating a shimmering moiré effect. Ultimately, even with these ties to specific Iranian and Western traditions, Shafie’s constructions evoke sensations of optical pleasure and discovery that knit together cultural vocabularies.

--Sarah Parrish

Aithan Shapira

(American, b. 1980)Hungerford Bridge, 2009

Collograph, 9 panels

84 x 107 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.1. Image courtesy of the artist.

It is commonly stated that Cubist artworks are the result of combining multiple views of a single object. But what does this really entail? Few have answered this question with as much complexity and depth as Aithan Shapira. Shapira’s life has always encompassed multiple viewpoints—some lived (time spent with an Aboriginal tribe in Australia) and some inherited (his mother a refugee of Iraq and ten generations of his father’s family in Jerusalem).

Shapira’s practice concerns both memory (experienced and inherited) and his place in a lineage of artistic tradition. Hungerford Bridge in London was first painted by Claude Monet in 1899, when it was still called Charing Cross Bridge. In his print Hungerford Bridge (2009), Shapira transforms Monet’s en plein air rapidity into a measured consideration of the elements of the scene, including not only what is visually present but also a historic and symbolic assessment of the bridge’s components.

Collography, the printmaking method that Shapira utilizes in this instance, entails the artist gluing diverse materials to a cardboard backing. This collaged plate is then inked and run through a press. The results are highly textured prints. Even in the monochromatic Hungerford Bridge we witness a rich range of deep, velvety tones and gauzy gray clouds, as well as sketchier, rougher passages. By using a collage technique, Shapira harkens back to the Cubists, who began to incorporate bits of found material into their paintings, but his scale is much larger. Combining multiple prints to form a grid more than six feet high and nearly nine feet wide, these works confront the viewer with a powerful experience of simultaneity.

--Kelly Presutti

Wael Shawky

(Egyptian, b. 1971)The Gulf Project Camp: Carved wood (after Khamsa 'Five Poems' by Nizami, 1442), 2019

Oil on carved wood

78 5/8 x 78 5/8 x 15 3/4 in. (199.71 x 199.71 x 40.01 cm)

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2019.2.10. Image courtesy Wael Shawky

Much of Wael Shawky’s artistic influence is lifted from the pages of Arab and Persian histories and epic poetry; this work was modeled after the Khamsa of Nizami Ganjavi, which served as a moral parable in 12th century Persia. Specifically, this piece includes a madrasa, or an Islamic center of education. The numerous patterned surfaces reference the geometric and floral motifs seen in Islamic architectural decorations, which wholly reject figural representation in favor of large expanses of tessellated surfaces. The distorted perspective seen in the aggressively slanted floor of the madrasa likely references the work of the 20th century Dutch designer M.C. Escher. Escher similarly drew inspiration from Islamic tile patterns for the construction of his characteristic geometric patterns.

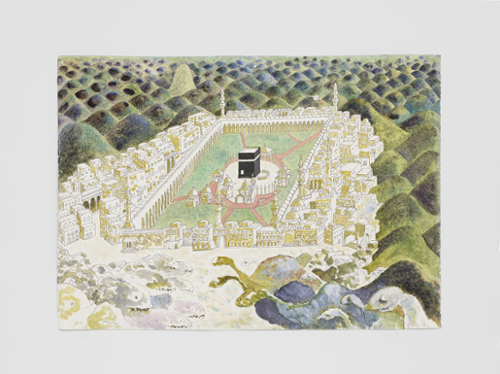

Wael Shawky

(Egyptian, b. 1971)The Gulf Project Camp: Drawing #1, 2019

graphite, ink, oil, and mixed media on cotton paper

19 7/8 x 27 5/8 in. (50.48 x 70.17 cm)

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2019.2.11. Image courtesy Wael Shawky.

Wael Shawky was born in 1971 in Alexandria, Egypt—where the artist currently maintains a studio—but he spent a large portion of his childhood in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. This drawing depicts an interpretation of literary themes in the tradition of Arab storytelling. In Drawing #1, Shawky depicts the landscape around the Kaaba, the building at the center of the holiest mosque in Mecca, morphing into giant mythical creatures. Similarly, in Drawing #33, Shawky includes a sea monster carrying a boat on its back in turbulent, muddied waters. Shawky’s fantastical body of work invites viewers to question belief systems through his overly sensationalized representations of history and faith.

Wael Shawky

(Egyptian, b. 1971)The Gulf Project Camp: Drawing #33, 2019

Graphite, ink, oil, mixed media on cotton paper

22 1/2 x 30 in. (57.15 x 76.2 cm)

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2019.2.12. Image courtesy Wael Shawky

Aithan Shapira

(American, b. 1980)Open Studio Curtain, 2011

Collograph, 9 panels

84 x 105 3/4 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.2. Image courtesy of the artist.

The first Cubists, Picasso and Braque, worked out a coded language between themselves, a mode of pictorial communication where the slightest curve could register as an absinthe glass and a circle crossed with lines could signify a guitar. Shapira has his own system of visual signs, and certain figures recur again and again—a candelabra, a life preserver, a ladder. Open Studio Curtain (2011) is a reprinting of a 2007 collograph, Before the Carnival. Yet just as the tone in which something is said can alter its meaning, here a shift in colors has transformed a brooding scene into a brightly lit interior. While Shapira encourages perceptual attentiveness, he also asks us to consider the malleability of language and the ways in which the same object can take on vastly different meanings depending on one’s viewpoint.

--Kelly Presutti

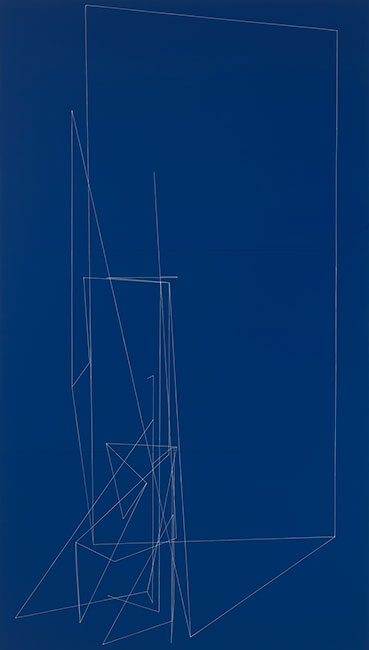

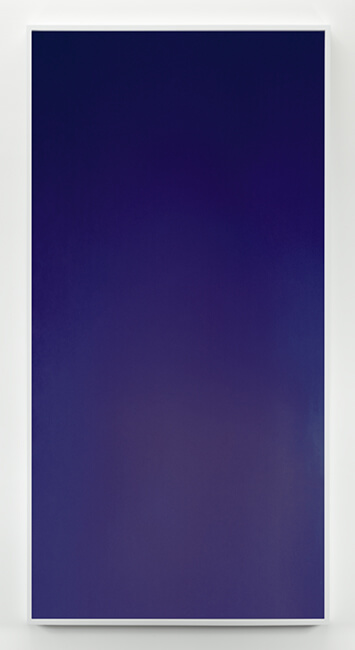

Kate Shepherd

(American, b. 1961)Blue Debris, 2010

Oil and enamel on panel

78 x 48 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond,© Kate Shepherd, 2013.34.35. Image courtesy of the artist and Galerie Lelong, New York.

Since the late 1990s, Kate Shepherd has developed a rigorous and analytical style of abstract painting. Her meticulous explorations of the mechanics of painting and the language of abstraction are fused with careful consideration of earlier investigations of the medium and conception by others––from Piet Mondrian to Agnes Martin, Robert Mangold, and Donald Judd. Working in oil and enamel on wood panels, Shepherd produces handsome orchestrations of shape, structure, surface, edge, space, color, and line.

Shepherd begins by preparing the panels with multiple layers of high-gloss enamel. Presented in varying sizes, the paintings are human scale, echoing a doorway or an open window. Their surfaces are a highly refined saturation of a single mesmerizing and nostalgia-inducing color: brick red, forest green, or midnight blue. The glossy surfaces reflect the available light to capture the movement of viewers and the still details of the surrounding space.

On top of these dense and striking pools of unbroken color, Shepherd draws in oil very thin gray or white lines that are neutral and airy. In long, deliberate, precise gestures, she creates her primary imagery: a delicate network of intersecting lines that angle this way and that throughout the picture plane. The lines describe architectural spaces, scaffolds, buildings, grids, and nets. The Etch-A-Sketch-like structure in Blue Debris (2010), for example, is convincing as a three-dimensional form from afar, but quickly flattens to an absorbing abstraction up close. By using found and computer-generated configurations, Shepherd employs a mixture of improvisational and fixed patterning to draw out a playground for her, and our, ideas and metaphors.

In her studio practice, Shepherd sets and follows a stringent set of guidelines and utilizes a consistent vocabulary of color and line, chance and gesture. The resulting paintings are elegant, generous, efficient, and strong. They unromantically reverberate within the vast history of abstraction while tackling the immensity and fragility of the space we inhabit.

--Alison J. Hatcher

Kate Shepherd

(American, b. 1961)Blue Space, Grid, 2012

Oil and enamel on panel

40 x 28 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.36. © Kate Shepherd. Image courtesy of the artist and Galerie Lelong, New York.

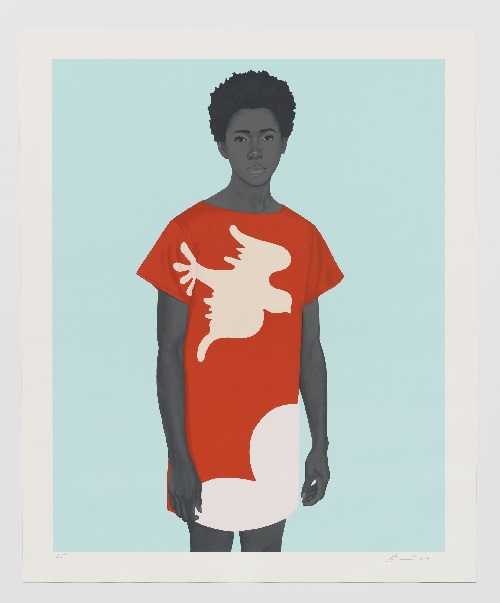

Amy Sherald

(American, b. 1973)Hope is the thing with feathers (The little bird), 2021

Color screenprint on Coventry rag

48 1/2 x 40 1/2 x 2in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2021, 1.24 © Amy Sherald. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth, photographer credit: Thomas Barratt

Born in 1973 in Columbus, GA, American artist Amy Sherald is known for her signature style of depicting African-American individuals in greyscale. The artist uses this technique, called "grisaille," to challenge the traditional associations between skin color and race. Sherald's goal, in her words, is to "paint Black people just being people." She chooses the subjects of her work by depicting passers-by doing everyday activities that make a lasting impression on her by a certain "weight and energy" in their spirit. "It's hard for me to find people to paint," she explains. "There has to be something about them that only I can see." Sherald developed her iconic style of portraiture by photographing those among these impressionable strangers who agreed to come to her studio. The artist creates portraits based on these photographs, often using bright colors and props to contrast the muted tones of the grisaille. Sherald’s distinctive style notably captured the imagination of First Lady Michelle Obama when, in 2018, the artist was commissioned to paint her official portrait for the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.

In this piece, Sherald depicts a dancer from the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in a relaxed pose, regarding the viewer with a decisive gaze. Standing against a blue background, the figure is represented wearing a red dress with a white bird in flight silhouetted across the chest. The title of this piece references a verse by American poet Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) that personifies hope as a bird perched in the soul, singing an everlasting "tune without words." This nod to the poet's work suggests a shared message of steadfast hope borne by the soul of an individual.

David Benjamin Sherry

(American, b. 1981)Above Abyss Blue Below, Point Reyes, California, 2015 / printed 2016

Chromogenic print

41 1/2 x 51 1/2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2016.3.25. Image courtesy of the artist, Moran Bonaroff, Los Angeles, and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

David Benjamin Sherry

(American, b. 1981)Canyon de Chelly, Chinle, Arizona, 2013 / printed 2016

Chromogenic print

51 1/2 x 41 1/2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2016.3.26. Image courtesy of the artist, Moran Bonaroff, Los Angeles, and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

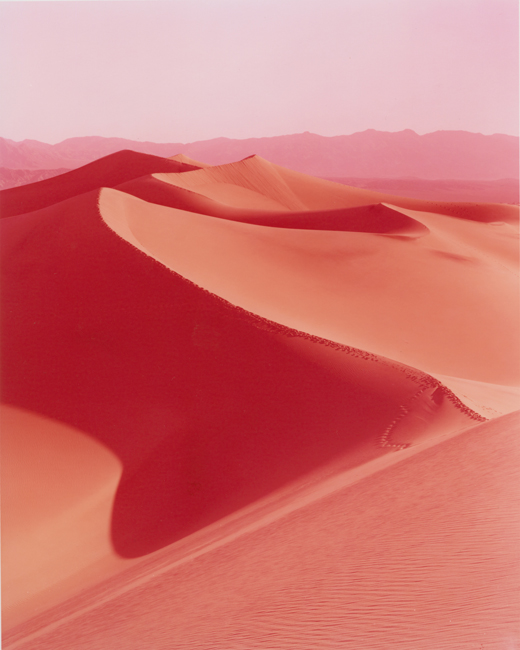

David Benjamin Sherry

(American, b. 1981)Sunrise on Mesquite Flat Dunes, Death Valley, California, 2013 / printed 2016

Chromogenic print

51 1/2 x 41 1/2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2016.3.26. Image courtesy of the artist, Moran Bonaroff, Los Angeles, and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

David Benjamin Sherry’s vibrant monochromatic landscape photography uses the American West as a subject for the expression of complex historical, cultural, political, and environmental concerns. Deeply affected by climate change as well as the exploitation of peoples and natural resources in lands that were once protected, the artist seeks to photograph the Western landscape in a way that alters how we view nature. Sherry adds brilliant color to the photograph during the final stages of development, imbuing the scenery with what he calls a “queer sensibility.” When assigning the color for each photograph, he takes into consideration the landscape’s distinct power; color enhances the composition by giving “this landscape a voice or a heartbeat.” In this depiction of the Mesquite Flat Dunes at Death Valley, vivid hues of pink and orange highlight the contours and texture of the striking dunes.

Yinka Shonibare

(British, b. 1962)Athena (after Myron), 2019

Fiberglass sculpture, hand-painted with Batik pattern, and steel base plate

82 3/4 x 35 3/8 x 27 5/8 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2019.2.17. © Yinka Shonibare / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Informed by his experience living in both England and Nigeria, Shonibare deconstructs multifaceted global histories and cultural identities in his works. Often exploring post-colonialism and globalization, the artist’s works are characterized by his incorporation of African wax print fabric. Inspired by Indonesian batik, manufactured in the Netherlands, and worn as popular fashion in West Africa, wax print embodies complex networks of cultural exchange and complicated globalized societies. The artist’s recent works reimagine the use of the fabrics by layering the vibrant patterns over classical works of Western art, such as this Roman sculpture of Athena. The resulting visual clash of cultures symbolizes the hybridity of history and identity within our global society. The artist underscores this point by replacing the goddess’s head with a globe. What began as a playful reference to the French Revolution transformed over time for the artist who says, “I felt that the globes, in a way, further extended that universality that represents all humans as opposed to a singular group.”

Yinka Shonibare

(British, b. 1962)The American Library Collection (The Great Migration: Poets, Philosophers, Historians), 2020

670 Hardback books, Dutch wax printed cotton textile, gold foiled names, bookcase, bespoke card catalogue box

98 x 120 x 13 1/4 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2020.1.18 © Yinka Shonibare CBE. All Rights Reserved, DACS/ARS, NY 2023

Amy Sillman

(American, b. 1955)3-Legged (Blue), 2015-16

Oil on canvas

75 x 66 x 1 1/2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2016.3.3. Image courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York.

Amy Sillman

(American, b. 1955)After Metamorphoses, 2015-16

Single-channel video on 5:25 min. looped, color, sound

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2017.6.62. Image courtesy of the artist.

A multitude of transfigurations occurring at a frenzied pace describe Amy Sillman’s video installation work, After Metamorphosis. The video is what Sillman refers to as an animated drawing and features a seamless loop of human and animal montages. It draws from Ovid’s epic narrative poem, Metamorphosis (8 CE)—a collection of fifteen books of mythological Greek stories. From the first book detailing a great flood brought to cleanse the earth from human sin, animals are established as emblems of neutrality or innocence throughout the poem, creating a sharp contrast to the vice and folly of man.

At the root of each story is the same plot: a passion fueled transformation of humans into animals to include snakes, a pig, a bull, a peacock, spiders, bats, a horse, bears, and birds. These occurred as acts of vengeance, though occasionally as reward, carried out by order of the gods. The tales are unrelated yet follow a chronological arrangement beginning with the throwing of rocks by two figures to indicate the creation of the world and concluding with the defiant proclamation, “I have finished a work that Jupiter’s wrath or fire or sword or the corruption of time cannot destroy” (XV.871). Composed of abstract drawings overlaid on iPad sketches, the film’s design patterns, shapes and sequence synchronize with the temporal, disconcerting soundtrack by Wibke Tiarks.

Elias Sime

(Ethiopian, b. 1968)Tightrope: Under the Stars, 2020

Reclaimed electronic components and wires on panel

153 ¼ x 110 ½ in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2021.1.7 © Elias Sime. Courtesy the artist and James Cohan, New York

Ethiopian artist Elias Sime creates intricate and visually complex abstractions from discarded electronic waste, which he buys in recycling markets in Addis Ababa, the Ethiopian capital. With labor intensive precision, the artist painstakingly braids electrical wires and cuts up old motherboards, incorporating computer keyboards and keys, buttons, bottle caps, bead-like plastic components, and other electronic parts, which he then re-assembles in elaborate patterns. The series title Tightrope suggests the precarious balance a society or community must maintain between technological advancements and their inevitable impact on the environment. Sime’s use of these materials is not intended as a commentary on the evils of consumerism, however. Suggestive of aerial views, topographical formations, and organic shapes accentuated by blocks of color, Sime’s compositions instead emphasize our interconnectedness, both to each other, and to the earth in an aesthetic language all his own.

Rose B. Simpson

(American, b. 1983)I Need You, 2023

Patinated bronze and clay bead earring

20 x 11 1/2 x 10 1/2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2023.1.24 © Rose B. Simpson. Courtesy of the artist, Jessica Silverman, San Francisco and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Rose B. Simpson is a contemporary, mixed-media artist whose practice examines the lasting effects of colonialism and the manifestations of personal and collective humanity. Born in Santa Clara Pueblo, New Mexico, Simpson finds inspiration in the earth of her ancestral homeland and in her indigenous upbringing and culture. Her sculptures are adorned with found objects like beads and leather and often contain the artist’s fingerprints and other markings that emphasize her physical engagement with the material. While this piece is cast in bronze, it was first realized in clay. Simpson combines ancient traditional pueblo pottery techniques she learned from her mother with innovative materials to create works that speak to her experience and have the potential to spark change: “My hope is that the works that are made make systemic change to benefit the planet. I’m working on building awareness around the energy of colonization, around indigenous culture, bodies, and place.”

Esphyr Slobodkina

(American, born Russia 1908-2002)Desert Moon, 1941

Oil on board

18 x 22 in.

The Alfond Collection of Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2017.15.5. Image courtesy of the Slobodkina Foundation, Northport, New York

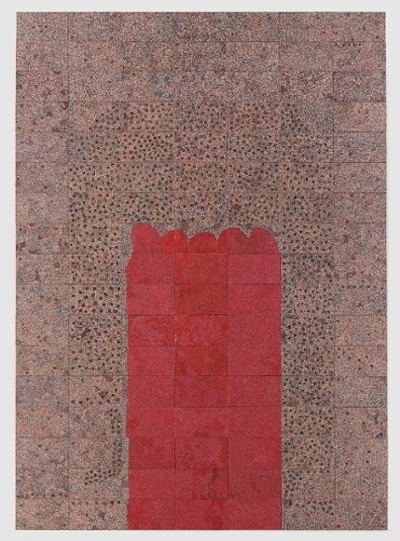

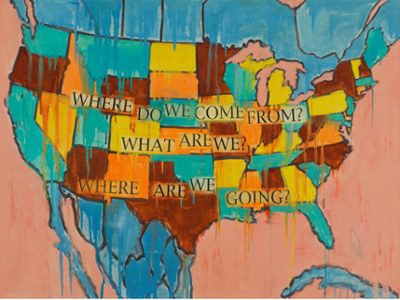

Jaune Quick-To-See Smith

(Native American, b. 1940)Where Do We Come From? 1, 2001

Mixed media on canvas

36 x 48 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2018.1.4. Image courtesy of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York

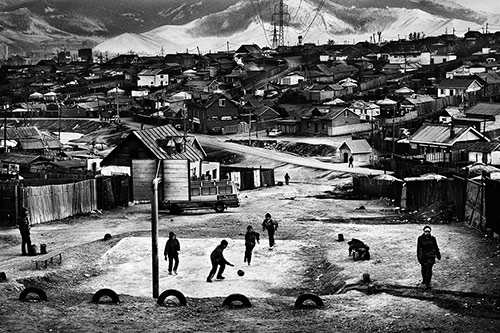

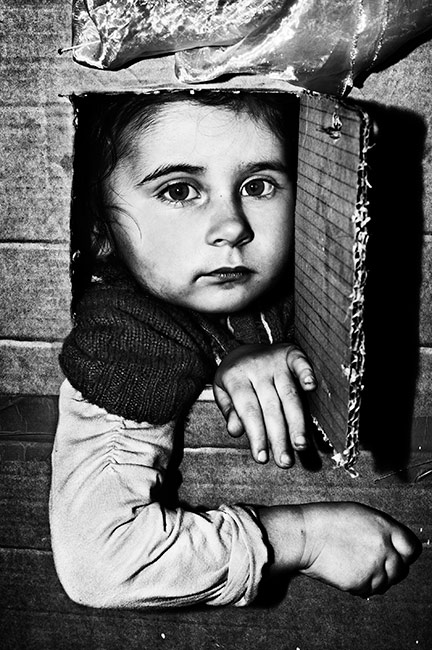

Jacob Aue Sobol

(Danish, b. 1976)Untitled #24, 2012

Gelatin silver print

20 x 24 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2015.1.33. © Jacob Aue Sobol. Image courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York.

Jacob Aue Sobol

(Danish, b. 1976)Untitled #39, 2012

Gelatin silver print

20 x 24 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2015.1.34. © Jacob Aue Sobol. Image courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York.

Jacob Aue Sobol

(Danish, b. 1976)Untitled #47, 2013

Gelatin silver print

20 x 24 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2015.1.35. © Jacob Aue Sobol. Image courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York.

Jacob Aue Sobol

(Danish, b. 1976)Untitled #54, 2013

Gelatin silver print

20 x 24 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2015.1.36. © Jacob Aue Sobol. Image courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York.

Jacob Aue Sobol

(Danish, b. 1976)Untitled #64, 2013

Gelatin silver print

24 x 20 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2015.1.37. © Jacob Aue Sobol. Image courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York.

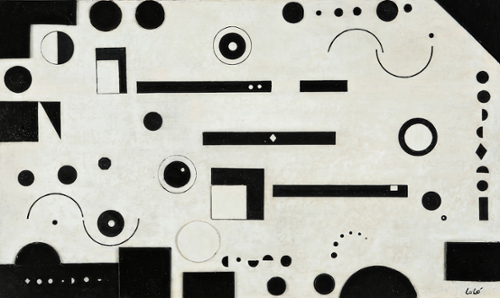

Loló Soldevilla

(Cuban, 1901-1971)Untitled (Sin Título), 1950

Mixed media on board

19 1/2 x 29 1/8 x 1 3/4 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2019.2.13. © Martha Flora Carranza Barba, universal heir of the work of Loló Soldevilla. Image courtesy Sean Kelly, New York.

Loló Soldevilla

(Cuban, 1901-1971)Untitled (Sin Título), n.d.

Oil on masonite

25 1/2 x 28 3/4 x 2 1/4 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2019.2.14. © Martha Flora Carranza Barba, universal heir of the work of Loló Soldevilla. Image courtesy Sean Kelly, New York.

A longtime member of Los Diez Pintores Concretos (The Ten Concrete Painters), Cuban artist Loló Soldevilla was a strong proponent of geometric abstraction. After the dissolution of De Stijl in 1931, an early 20th century movement that sought to reduce art to its most elemental components in search of order and harmony, Soldevilla and other artists created a unique style devoid of symbolism and references to reality. The two works in the museum’s collection rely exclusively on the relationships

between simple shapes and color contrasts. Unlike some of her fellow abstractionists, Soldevilla was mostly self-taught and began experimenting with painting and sculpture in her late forties. A political, women’s rights activist and cultural advocate, Soldevilla also owned an art gallery and curated significant exhibitions to promote abstraction nationally and abroad. The artist continued producing art until her passing in 1971.

Vaughn Spann

(American, b. 1992)Transition within two states, 2020

Polymer paint, mixed media on aluminum

60 x 96 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2020.1.13 © Vaughn Spann

Vaughn Spann was born in Florida and currently lives and works in New Haven, Connecticut. In his artistic practice, he investigates issues of memory, personal experience, history, time, and space. In each piece, Spann emphasizes the formal elements contained within the work—color, shapes, and marks take on new meaning. His visual vocabulary oscillates between the figural, the abstract, and the gestural, and often addresses socio-political issues. This work is part of Spann’s Marked Man series, which features prominently the letter X against a colorful background rich with thick markings. The X is a reference to the artist’s personal experience: “They came from an interest in assigning new meaning to an extremely recognizable form. How can I take an X, allow it to be my muse for painting, invite conversations of color, line, form, yet allow it to open deeper conversations. I found myself severely traumatized by a stop and frisk altercation during college as I was profiled by the police while leaving a study session. I felt the weight of having to spread my legs and hold my hands up in the air which feels defenseless, violated and infuriated which sparked an interest into the form.”

Haim Steinbach

(American, b. 1944)Untitled (travel bag), 2012

Wood, plastic laminate and glass box; travel bag

50 1/2 x 59 21/64 x 23 21/64 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.115. Image courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York.

Haim Steinbach, like many artists in the late 1970s and early 1980s, felt that painting, originality, and subjective creation were exhausted, and turned his attention to mass-produced objects circulating in daily life. From store shelves and tag sales, he began to select objects of interest — a new pair of sneakers, a lava lamp, a rubber Kong dog toy, a ceramic soup tureen shaped like a cabbage — and arrange them on carefully constructed shelves. In his groupings, seemingly divergent items — or series of items — evoke uncanny connections through their formal resonances, historical and social allusions, and shared status as commodities. Steinbach's artistic practice of selection and presentation leverages consumer desire and commodity relations to reexamine the status of art. He recognizes the agency of everyday things and sets out to explore and intensify the effects of things on viewers.

In Untitled (travel bag) (2012), Steinbach places an iconic blue Pan Am travel bag on a glass shelf in a plain wooden frame attached to the wall. The display alludes to the Minimalist wall sculptures of Donald Judd while disquietingly merging a museum frame with a shelf in a store, thereby equating high art with its lowly cousin, commodity. Inside, he places a single bag made from the synthetic material PVC (polyvinyl chloride) by the U.S. airline Pan American World Airways ("Pan Am"), which pioneered the concept of modern air travel. The company's retro globe logo, which covers the face of the bag and repeats across zipper pulls and tassels, recalls the late 1960s, a time when Pan Am reached its zenith and carried millions of passengers a year to all parts of the world. With its practical pockets and carry-on size, the bag is an artifact, as well as a symbol, of our globalized world, where bodies, things, and capital move freely. By choosing and framing this single bag, Steinbach focuses attention on it as a physical object and as a sign or simulacrum, a reference to an imagined reality. His placement of the dark blue, dome-like form near the center of the square, isolated from the rest of the world, simultaneously evokes a religious portrait, perhaps of the Virgin Mary, and a high-end designer display. It is the space, or lack thereof, between such extremes—religion and capitalism, the unique and the multiple, art and commodity—that interests Steinbach. His artworks speak in a bizarre and mundane language of things taken from the world and given back to the world anew.

--Ruth Erickson

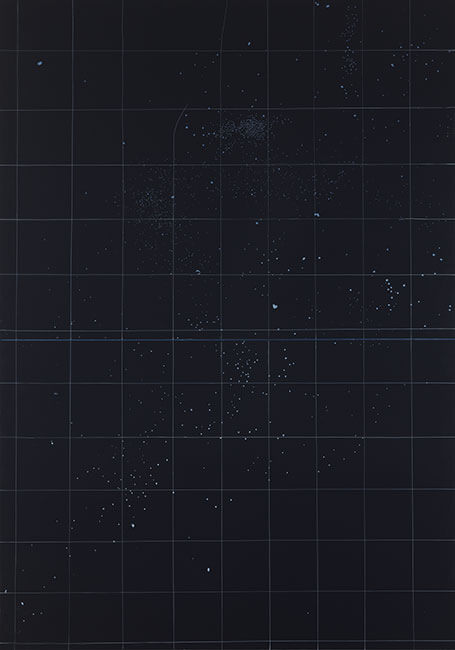

Tavares Strachan

(Bahamian, b. 1979)Gameboy, 2019

Oil, enamel, and pigment on acrylic

36 x 36 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2020.1.17 © Tavares Strachan

Born in the Bahamas, Tavares Strachan is among a group of compelling young artists driving the global art movement around issues of identity and social justice. Strachan’s ambitious, open-ended practice operates at the intersections of art, science, history, and politics, and his interests are wide-ranging, from aeronautics to astronomy to climate extremes. The artist mines these subjects to tell stories of cultural displacement and human aspiration in an effort to bring attention to issues of invisibility and to affect societal change. Gameboy is part of a series of collage and mixed media works that continue Strachan’s ongoing project to surface the unseen contributions and unrecorded histories of communities of color. With its map of constellations, game console schematic, silver bullets hanging vertically like raindrops, photographs of glaciers and water, and a repeated portrait of the Ethiopian leader Haile Selassie, the piece is emblematic of Strachan's style.

Mary Ellen Strom

(American, b. 1955)Tree Line (silver), 2013

Digital c-print

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2016.3.21. Image courtesy of the artist.

Mary Ellen Strom

(American, b. 1955)Tree Line (silver with green), Digital c-print

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2016.3.20. Image courtesy of the artist.

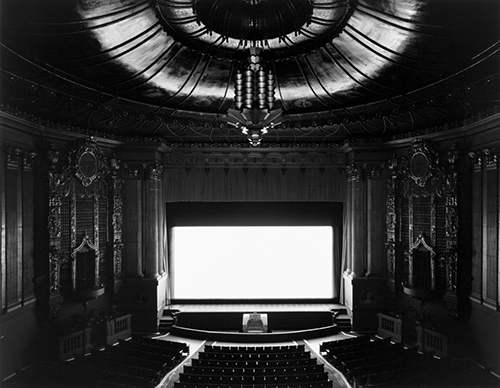

Hiroshi Sugimoto

(Japanese, b. 1948)Castro Theater, 1992

Gelatin silver print

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2015.1.17. © Hiroshi Sugimoto. Image courtesy of Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

Hiroshi Sugimoto

(Japanese, b. 1948)Regency, San Francisco, 1992

Gelatin silver print

16 3/4 x 21 1/4 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2015.1.16. © Hiroshi Sugimoto. Image courtesy of Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

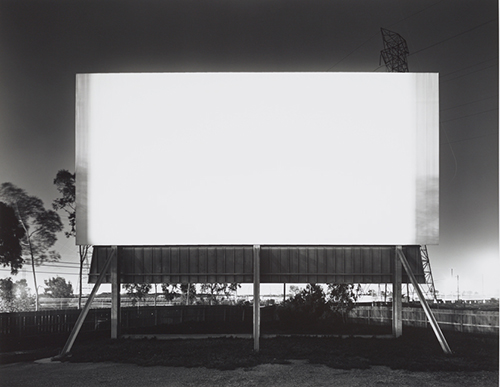

Hiroshi Sugimoto

(Japanese, b. 1948)South Bay Drive-In, 1993

Gelatin silver print

16 3/4 x 21 3/8 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2015.1.18. © Hiroshi Sugimoto. Image courtesy of Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

Hiroshi Sugimoto

(Japanese, b. 1948)Manatee, 1994

Gelatin silver print

47 x 58 3/4 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2014.1.42. © Hiroshi Sugimoto. Image courtesy Pace Gallery.

Becky Suss

(American, b. 1980)Houseboat on Dull Lake in the Valley of K, 2019

Oil on canvas

84 x 144 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2019.2.22. © Becky Suss. Image courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Rufino Tamayo

(Mexican, 1899-1991)Cabeza, 1977

Mixografia on paper

12 5/8 x 16 ½ in

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2020.1.7 © Rufino Tamayo/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Rufino Tamayo

(Mexican, 1899-1991)Estela, 1977

Mixografia on paper

29 59/64 x 22 3/64 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2020.1.8 © Rufino Tamayo/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Rufino Tamayo

(Mexican, 1899-1991)Sandías, 1977

Mixografia on paper

29 1/16 x 20 51/64 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2020.1.9 © Rufino Tamayo/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

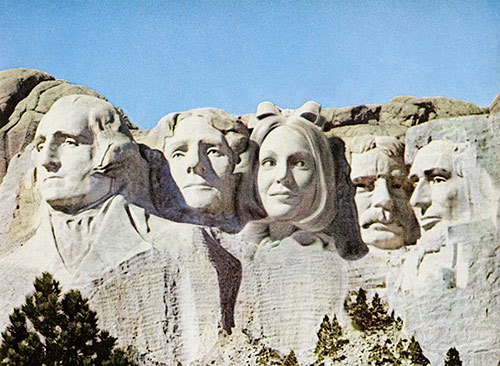

Hank Willis Thomas

(American, b. 1976)Behind every great man..., 1973/2015, 2015

Digital Chromogenic print

38 5/8 x 50 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2015.1.39. Image courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Hank Willis Thomas, Emily Shur and For Freedoms

(American, b. 1976)Freedom from Fear, 2018

Archival pigment print

54 x 43 1/4 x 2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2018.1.28 © For Freedoms

These works by Hank Willis Thomas and Emily Shur recreate the original representation of the four freedoms by American artist Norman Rockwell, more than seventy years later, in the context of contemporary society. The reimagined scenes portray the complexity and diversity of the American public absent from the Rockwell depictions. Each of these images reinforces the importance of inclusivity and the heterogeneity that characterizes America’s social fabric. By giving a prominent role to people of diverse ethnic backgrounds, ages, and faiths, Thomas and Shur encourage viewers to reflect on how we define America and what each of these freedoms means today.

These prints were created in the context of the For Freedoms 50 State Initiative founded by artists Eric Gottesman and Hank Willis Thomas in 2016. The platform, which continues to be active, is the largest artistic collaboration in American history; it provides opportunities for engagement, action, and public discussions to foster equality and democratic participation. This collaborative project strives to activate civic engagement across platforms for the American public. To learn more visit forfreedoms.org

Hank Willis Thomas, Emily Shur and For Freedoms

(American, b. 1976)Freedom from Want, 2018

Archival pigment print

54 x 43 1/4 x 2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2018.1.29 © For Freedoms

Hank Willis Thomas, Emily Shur and For Freedoms

(American, b. 1976)Freedom of Speech, 2018

Archival pigment print

54 x 43 1/4 x 2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2018.1.30 © For Freedoms

Hank Willis Thomas, Emily Shur and For Freedoms

(American, b. 1976)Freedom of Worship, 2018

Archival pigment print

54 x 43 1/4 x 2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2018.1.31 © For Freedoms

This photograph shows a diverse group of worshippers, some gazing down, while others close their eyes, or look out. The sharply focused image and the strategic compositional arrangement highlight the individual identity of each figure. Objects and garments used in various religious traditions make evident the heterogeneity of the group depicted.

Hank Willis Thomas and Emily Shur created this work in 2018 as part of a series that reimagines Norman Rockwell’s original Four Freedoms illustrations that appeared as 1942 covers for The Saturday Evening Post. In Thomas’ words, “[Rockwell] was one of the people who really shaped the iconography of America... there are a lot of people who are missing in those images.” In this project, Thomas and Shur reinterpreted Rockwell’s image by representing the modern, vast religious and spiritual diversity within the American public. The peaceful coexistence within this image asserts that all Americans deserve the freedom to practice religion, respect when practicing, and representation of their belief system in mainstream art/society.

Hank Willis Thomas

(American, b. 1976)Freedom Riders (Spectrum),, 2021

UV print on retroreflective vinyl mounted on Dibond

10 x 120 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2021.1.9 © Hank Willis Thomas

Hank Willis Thomas

(American, b. 1976)The Cotton Bowl, 2011

Digital C-print

50 x 73 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2014.1.25. Image courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Hank Willis Thomas explores the perception and presentation of African Americans in popular culture through a photography-based practice that exploits the very visual language of contemporary media. Underscoring what W. E. B. Du Bois termed the “double consciousness” of African American identity—the condition of seeing oneself reflected through the (often negative) perspective of others—Thomas employs doubling, mirroring, and pairing as his key compositional and conceptual tools. In doing so, he further underscores his medium’s ingrained capacity to replicate imagery and implicates photography and its commercial use in forming and deforming black American identity.

The Cotton Bowl (2011) is a succinct and sharply symmetrical pairing of two men in the guises of a post-slavery era sharecropper and modern-day football player. The field’s line of scrimmage separates and mirrors the past and present, under a century apart, as both figures crouch in identical positions, picking cotton and in a three-point football stance. Thomas articulates a clear parallel between contemporary sports and agriculture’s legacy of slavery as two industries fueled by the bodies and labor of African Americans. In his work, he often critiques the culture of sports and its ancillary marketing industry for its use and depiction of the black male body as a site for profit. The juxtaposition in The Cotton Bowl visualizes this troubled relationship between race and sports in the United States, chastising the latter for its exploitation of young men through a culture that hinges on spectacle and a violence whose depth is only now becoming public.

Exploring and exposing undercurrents of racial bias within our ever-absorbing media environment, Thomas asks us to consider the present and past in new light. “Ultimately,” the artist explains, “my goal is to subvert the common perception of ‘black history’ as somehow separate from American history.”

--Dina Deitsch

Click here to view Hank Willis Thomas’s insights on this work.

Hank Willis Thomas

(American, b. 1976)I am the Greatest, 2012

Mixed Media

33 1/2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2016.3.18. Image courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Like much of Thomas’s work, I am the Greatest addresses themes of identity, popular culture, and social justice. This work is an enlarged reproduction of a pin-back button released in the 1970s. Pin-back buttons were used throughout the twentieth century as a means of galvanizing support for social movements through both financial support in the purchase of buttons, and the physical action of identifying oneself as a member of a movement. The original “I am the Greatest” button relates to Muhammad Ali, who took center stage in the realms of sports, popular culture, and political activism. In fact, Ali once stated, “I’m not the greatest. I’m the double greatest. Not only do I knock ‘em out, I pick the round. I’m the boldest, the prettiest, the most superior, most scientific, most skillfullest fighter in the ring today.” Ali’s words, now immortalized in Thomas’s work, boldly challenge white supremacy by claiming one’s humanity, worth, and greatness in the public sphere.

Hank Willis Thomas

(American, b. 1976)She keeps me warm, 2014/2015, 2015

Digital Chromogenic print

45 15/16 x 40 15/16 x 1 3/4 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2015.1.41. Image courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Hank Willis Thomas

(American, b. 1976)Walk like a man, 1978/2015, 2015

Digital Chromogenic print

41 7/8 x 40 7/8 x 1 3/4 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2015.1.40. Image courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

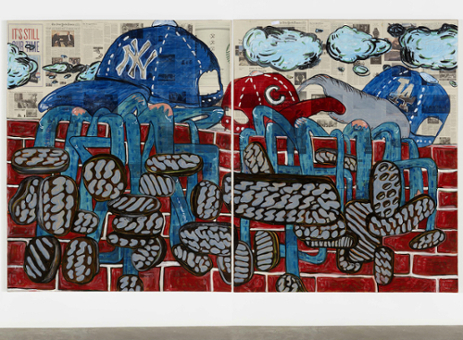

Rirkrit Tiravanija

(Thai, b. 1961)untitled 2018 (MARCH ON UNTIL IT RAINS GLASS no. 2), 2018

Acrylic and newspaper on linen

87 1/2 x 143 21/64 x 2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art,Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2018.1.27. Image courtesy of the artist.

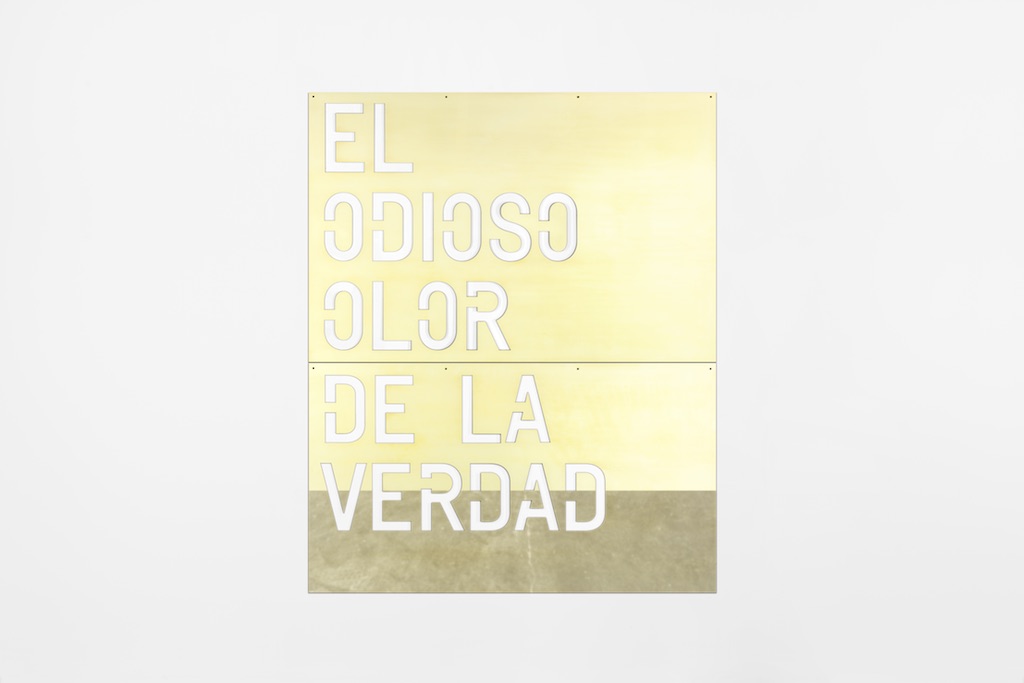

Rirkrit Tiravanija

(Argentinian, b. 1961)untitled (El odioso olor de la verdad), 2020

.063" brass mirror

73 15/64 x 89 3/8 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2020.1.5. Image courtesy of the artist and kurmanzutto, Mexico City/New York.

Fred Tomaselli

(American, b. 1956)April 9, 2020, 2020

Gouache, collage and archival inkjet print on watercolor paper

11 x 12 ¼ in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2020.1.10 © Fred Tomaselli 2020. Image courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York.

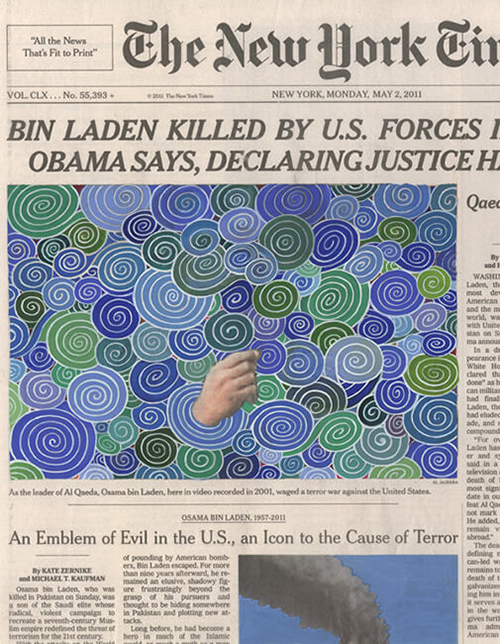

This work is part of the series The Times, which Fred Tomaselli began on March 16, 2005, by altering the front page of The New York Times from that day. Since then, Tomaselli has produced dozens of works that incorporate the iconic newspaper. For each one, he prints a section of the front page on watercolor paper and alters the original photograph by painting colorful patterns over it. The resulting image retains some of the original text, figures, and objects, as well as the fonts and layout characteristic of the Times. Tomaselli created this work at the height of the Coronavirus pandemic. Although at first glance the use of bright colors and geometric shapes may give the appearance of playfulness and whimsy, the artist challenges our expectations and examines how perception functions in relation to the consumption of mass media.

Fred Tomaselli

(American, b. 1956)Jan 26, 2013, 2013

Gouache on printed watercolor paper

10 3/4 x 12 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.60. © Fred Tomaselli. Image courtesy of the artist and James Cohan Gallery, New York/Shanghai.

Fred Tomaselli is a contemporary painter known for incorporating a wide range of unorthodox materials—from prescription pills and hallucinogenic plants to images cut from magazines and books. In his paintings, he arranges these bits into elaborate and kaleidoscopic motifs that recall cosmic events, biomorphic forms, and indigenous decorative patterns before he seals them in a thick layer of clear epoxy. Strata of pigment and imagery seem suspended in space and time, drawing viewers into complex, sumptuous compositions.

Around 2009, Tomaselli began a series of works that take the front page of the New York Times as the starting point. He screen prints a section of the front page onto watercolor paper and then uses gouache paint to alter and reinterpret the press photographs. Tomaselli's signature motifs mask and reveal parts of the image to generate evocative compositions that play with the surrounding text. In May 2, 2011, the lead headline announces that U.S. forces have killed Osama Bin Laden, whom a lower headline describes as "an emblem of evil in the U.S., an icon to the cause of terror." Between these two headlines, a single hand emerges from the center of an azure blue spiral in a field of blue and green spirals. The image resembles the hand of God, a motif frequently found in Christian and Jewish art to indicate God's involvement in and approval of earthly acts. We learn from the caption that the original image was a still from one of the many videos Bin Laden made and distributed to publicize his menacing plans (commanded, according to Bin Laden, by God). Tomaselli thus transmutes Bin Laden's own hand into a symbol of divine intervention in the killing of Bin Laden. Such an intricate and contradictory circuit of signification reflects the difficulties of the War on Terror.

Tomaselli's newspaper works complicate relations between image and text. The pictures no longer serve simply to illustrate the accompanying story, but rather to obscure, expand, or introduce alternative and sometimes subversive ideas. In Jan. 26, 2013, he repaints a massive barrier in Cairo to resemble colorful, childlike blocks that Egyptian demonstrators are attempting to topple.

--Ruth Erickson

Fred Tomaselli

(American, b. 1956)July 25, 2012, 2012

Gouache on printed watercolor paper

12 x 10 1/2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, © Fred Tomaselli. Image courtesy of the artist and James Cohan Gallery, New York/Shanghai.

In July 25, 2012, he covers a photograph of Syrians fleeing the ancient city of Aleppo with a blue star pattern resembling the adornment found in historic mosques that face the threat of wartime destruction. Tomaselli's artistic reinterpretations of the front page render the fleeting nature of the news into something timely, enduring, and heartbreakingly beautiful.

--Ruth Erickson

Fred Tomaselli

(American, b. 1956)May 2, 2011, 2012

Gouache on printed watercolor paper

11 x 3 3/8 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.59. © Fred Tomaselli. Image courtesy of the artist and James Cohan Gallery, New York/Shanghai.

Juan Travieso

(Cuban, b. 1987)Lonesome George, 2013

Oil and acrylic on canvas

48 x 72 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.95. Image courtesy of the artist.

After extensive study of birds and tortoises from islands of the Galapagos in the early 1830s, Charles Darwin produced the scientific theory of evolution he referred to as natural selection. Because the tortoises had evolved separately from one another for hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of years, Darwin could tell which were from what island based on the shape of their shells. In June of 2012, Lonesome George, the last Pinta Island tortoise and the rarest creature in the world, died at the Galapagos National Park. The extinction of this indigenous tortoise subspecies, the subject of Juan Travieso’s Lonesome George (2013), was caused in large part by the decimation of vegetation by goats that had become feral after being introduced to the island. The event underscores Darwin’s interest in evolutionary issues of influence, struggle, temporality, and new structures for understanding life.

Travieso engages these themes through a geometricizing vernacular of realism, portraiture, and abstraction. The protagonists of his vivid paintings have consisted largely of animals in harm’s way, from monkeys used in animal testing to endangered species of bears and birds. Soft—even tender—in their realistic rendering, the faces of these creatures are met by sharp geodesic and pyramidal forms. Geometric accumulations of color bury themselves in feathers and furry coats, extend from beaks, snouts, and animal faces, and dot the landscape like highly chromatic crags.

While the purpose of these works is to raise awareness about endangered animals, paintings like Lonesome George also raise questions about our own evolution. What parts of our culture will we let die off? How will we evolve socially and biologically in an increasingly digital culture? The artist’s pairing of natural forms with lush geometric embellishments points to both technological advancement and impermanence. By picturing creatures in peril, Travieso suggests as much about the vulnerability of the human species as he does about its threat to others.

--Evan J. Garza

Click here to view Juan Travieso's insights on this work.

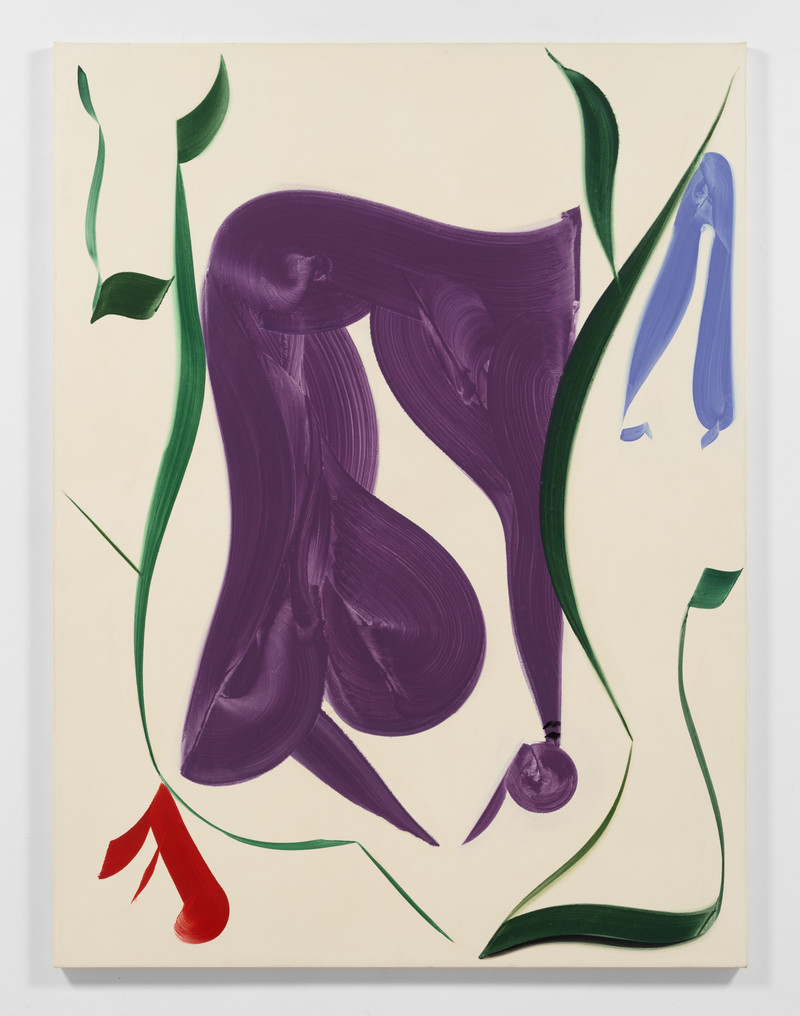

Patricia Treib

(American, b. 1979)Violet Sleeve, 2022

Oil on Canvas

72 x 54 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2023.1.8 © Patricia Tribe, Courtesy of the artist and Bureau, New York

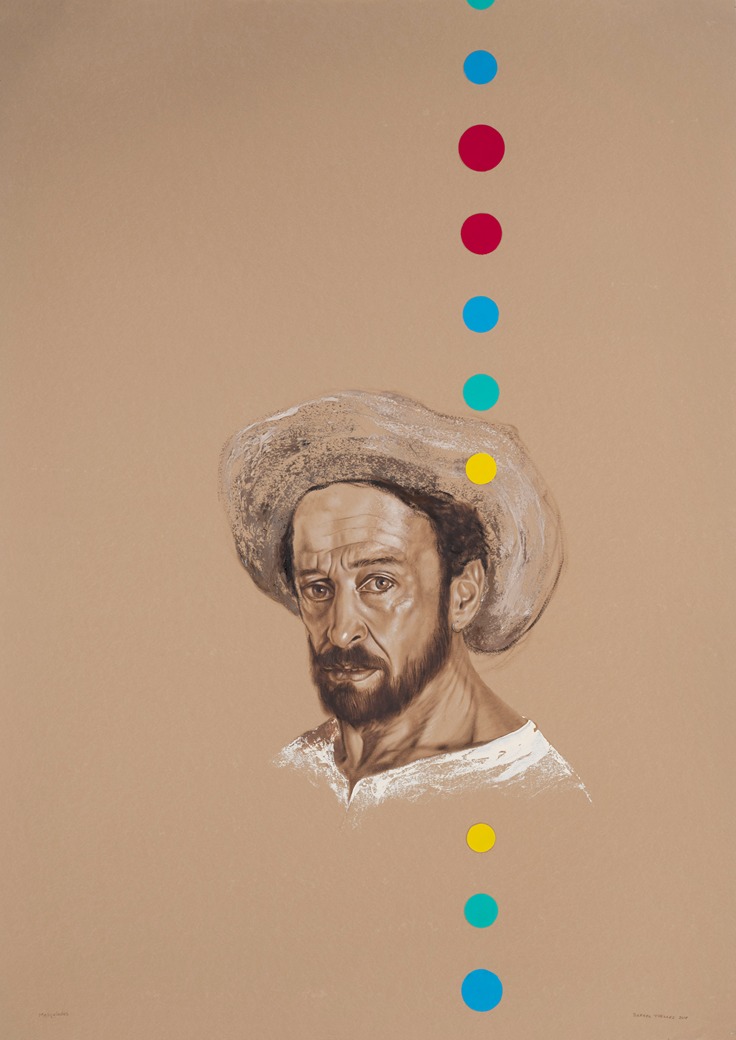

Rafael Trelles

(Puerto Rican, b. 1957)Gitano, 2018

Etching ink and acrylic on Kraft rising Stonehenge paper

54 x 40 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2021.1.37 Image courtesy of the artist

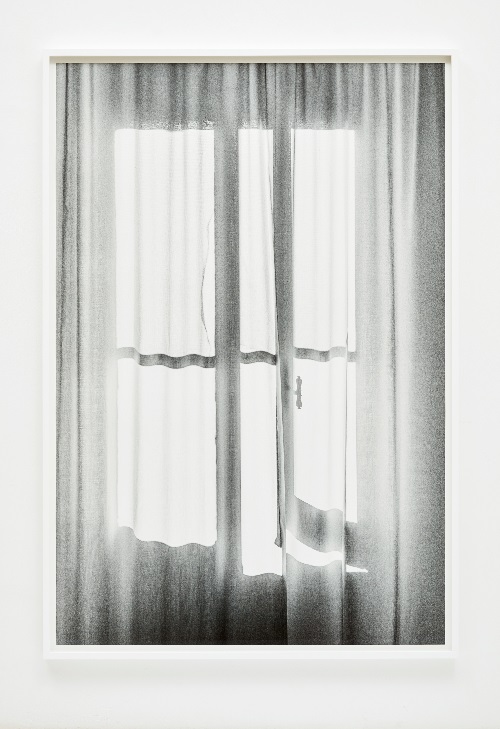

Su-Mei Tse

(Luxembourgian, b. 1973)Morning Light (Rome) #2, 2018-21

Inkjet on fine art paper

63 x 42 1/8 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2021.1.30 © 2021 Su-Mei Tse

Multidisciplinary artist Su-Mei Tse expresses memory and transitory emotional states through

photography, video, sculpture, and installation. Born in Luxembourg and beginning her career as

a classical cellist, Tse moved to Paris to pursue a degree in Visual Art. The artist’s oeuvre is

closely entwined with her background as a musician, as she often investigates the effects of

sound on perception. Her work encapsulates fleeting yet profound moments in life experienced

within the psyche and seeks to articulate them into visual form. Exploring the passing of time,

thought, and feeling, Tse’s work can be approached from many angles.

In Morning Light (Rome) #2, Tse uses light as a formal tool, creating a monochromatic image

informed by her recollection of quiet moments of a morning spent in Rome as seen through an

open window obscured by a translucent curtain. The artist captures the subtle beauty of the first

hours of daylight and focuses on the contrast between light and dark. As is the case with many

of her works, a single meaning remains elusive, and the work is shrouded within a multiplicity

of layered themes, such as time, geography, and feeling. Meditative and ethereal, Morning Light

encourages the viewer to contemplate what lies beyond the obscuring curtain.

Sara VanDerBeek

(American, b. 1976)Metal Mirror II (Magia Naturalis), 2013

Digital C-print and Mirona glass, ed. 1 of 3

96 x 48 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.076. Image courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Sara VanDerBeek’s practice thrives at the juncture of past and present, the ephemeral and the permanent. Previous series were devoted to the creation of sculptures that existed only as long as it took for her to fix them in restrained, carefully composed photographs. Although VanDerBeek now allows her sculptures to have a life beyond the studio, her earlier practice of imposing durational limits on her constructions demonstrates how time itself has always been an essential element of her practice.

As part of her most recent body of work made at the Memmo Foundation in Rome—where she was able to study the monuments as well as the more intimate textures of the ancient city—VanDerBeek created a series of seven photographs called Metal Mirrors. Each is comprised of a close-up of an oxidized metal wall, presented at 8 x 4 feet and laid beneath semi-transparent, tinted and mirrored glass. They encompass the viewer with their scale and reflective surface and are uniquely activated as new subjects glimpse themselves in these minimalist yet painterly objects. The momentary layers of these fleeting images, permeable and evanescent, continue the artist’s temporal exploration, as well as her inquiry into the magic and mechanics of photography.

When first invented in the 1820-30s, the photographic image was a revelation. Still, despite our scientific understanding of the process, the experience of making an image—especially with film—contains equal parts wonder and wish. Like the internal mirror that is essential to VanDerBeek’s SLR film camera, her Metal Mirrors catch and bounce back information. With their veneers of glass, the photographs have become objects themselves, but they also operate as a sort of lens. When caught in their reflection, we see ourselves anew.

VanDerBeek’s Metal Mirrors, with their layers of print, color, and reflection, suggest an alchemical transformation, and themselves represent the cycling of subject and object. Their mirrored surfaces implicate the viewer—in our looking, we are also seen. As VanDerBeek’s works connect us to allusions of history, we are presented over and over with the opportunity to discover ourselves set in present time against a past moment.

--Abigail Ross Goodman

Sara VanDerBeek

(American, b. 1976)Metal Mirror IV (Magia Naturalis), 2013

Digital C-print and Mirona glass, ed. 1 of 3

96 x 48 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.77. Image courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Sara VanDerBeek

(American, b. 1976)Metal Mirror V (Magia Naturalis), 2013

Digital C-print and Mirona glass, ed. 1 of 3

96 x 48 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.78. Image courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Sara VanDerBeek

(American, b. 1976)Roman Woman X, 2013

Digital c-print

20 x 16 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2014.1.12. Image courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Goddesses of the past often occupy prominent spaces within museum galleries. The female form has served as a dynamic and frequent inspiration from antiquity to the present. In Roman Women X, Sara VanDerBeek contemplates how the body has been presented and contested throughout art history. This photograph belongs to a larger series of works in which the artist represents various ancient sculptural forms reimagined in blue and purple hues. Although her source material now exists in various shades of white stone, the ancient sculptures were originally painted in bright colors. VanDerBeek’s own palette echoes this historical precedent, while simultaneously yielding her own distinctive aesthetic vision.

In regards to her exploration of antiquity, VanDerBeek explains, “I have always had an interest in classical sculpture, and in particular, the photographic reproductions of it that are found in art history anthologies. They are iconographic and symbolic of our ideas of the past and our ideals—but more importantly they are, in their current state, a meeting of times.”[1] Roman Women X was inspired by the artist’s trips to Rome, Naples, and Paris to view Classical and neoclassical sculpture. The artist noted the repetition of poses and figural forms in the sculptures, and identified a relationship between this serial aspect of ancient art and the replication of photographic prints from a single image.

The striking purple hues in this photograph are also evident in other bodies of work by VanDerBeek.[2] This unusual color choice evokes a dream-like state, echoing the artist’s experience while photographing these ancient objects in a spaced steeped in history. Moreover, the perspective of the photograph infuses the image with a fantastical or ethereal quality: the sculptural fragment appears to float within the composition, and the artist intriguingly leaves space above the sculpture where its missing head might appear. Beyond traditional representations of antiquity, VanDerBeek’s photographs inspire consideration of time, place, and space and the construction of iconic imagery.

--Amy Galpin

[1] Andrew M. Goldstein, “Sara VanDerBeek on Making the Classical Past Contemporary,” Artspace, July 30, 2013, accessed August 1, 2014, http://www.artspace.com/magazine/interviews_features/sara_vanderbeek_interview.

[2] In the Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, for example, see Metal Mirror II (Magia Naturalis), digital c-print, 2013; Metal Mirror IV (Magia Naturalis), digital c-print, 2013; and Metal Mirror V (Magia Naturalis), digital c-print, 2013.

Hellen van Meene

(Dutch, b. 1972)Greta Thunberg, Stockholm, 2019

Chromogenic print

15 3/8 x 15 3/8 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2019.2.21. © “Hellen van Meene”. Image courtesy of the artist and Yancey Richardson, New York.

Dutch photographer Hellen van Meene was commissioned by TIME magazine to photograph Greta Thunberg, the climate change activist, during one of Thunberg’s school strikes for the May 27th edition. She photographed Thunberg in a stark, shadowy, desolate concrete corridor in Stockholm’s Old Town of Gamla Stan near the Swedish Parliament. Thunberg, fashioned here in a green dress selected by the photographer to symbolize “life,” contrasts her bleak surroundings that represent the possible future of her generation if the world does not take action. The artist adds, “We shouldn’t see Greta as a young cute thing; she’s a serious girl with a serious message.” In addition to her climate activism, Thunberg has been vocal about her Asperger’s syndrome diagnosis and has shared how this has positively impacted her life and work: “I have Asperger’s syndrome and that means I’m sometimes a bit different than the norm. And-given the right circumstances-being different is a superpower."

Danh Vo

(Danish, b. 1975)We The People (Detail), 2011-16

Copper

91 x 66 x 22 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2018.1.19 © Studio Danh Vo

Vietnamese-born Danish conceptual artist, Danh Vō, ruminates on themes of cultural identity and community. This work is a part of the series We The People in which the artist recreated a full-scale copper replica, in 250 pieces, of Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi’s (1834-1904) iconic The Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World. A symbol of freedom, the monument in its early years welcomed immigrants on ships arriving at Ellis Island to America, and it still today deeply resonates with audiences. Like many who encounter the statue for the first time, the artist saw a strong, imposing monument, but with a closer look was struck by the delicate, thin, hollow structure. The various pieces that make this series, including this part of Liberty’s garment, exist in collections throughout the world, never to be brought together to reconstruct the monument in its entirety. The fragments of We The People both physically and conceptually symbolize the fragility of freedom.

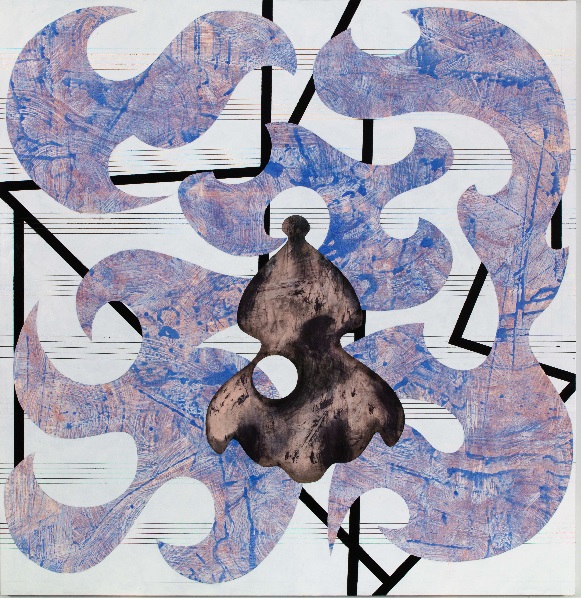

Charline Von Heyl

(German, b. 1960)Lady Moth, 2017

Acrylic and charcoal on linen

90 x 82 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2018.1.24. Image courtesy of the artist and Petzel Gallery, New York.

Charline Von Heyl

(German, b. 1960)Tipdipso, 2013

Acrylic and oil on canvas

86 x 82 1/4 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2014.1.59. Image courtesy of the artist and Petzel Gallery, New York. Photo credit: Jason Mandella.

Charline von Heyl’s works on canvas are calibrated to make viewers conscious of the ways in which they perceive a painting. The German-born, United States–based artist refuses to adhere to a signature style and, each time she takes up her brush, confronts anew how a painting is made, especially with regard to the hierarchy between foreground and background. Her use of color is frequently cacophonous, though occasionally restrained to tease the eye. Von Heyl does not tame her paintings for beauty; rather she trains her viewers to look actively and long enough for the awkward and rebellious aspects of her paintings to give way to intertwined, complex planes of imagery. In attempting to “rewind” a von Heyl painting—to unravel the order of the gestures and marks—viewers are consistently foiled. In maintaining the mystery of her paintings and holding viewers in their thrall, von Heyl wields her power.

“Where to begin?” is a fundamental question asked by anyone trying to describe a von Heyl painting. Our gaze faces the same challenge. In the case of Tipdipso (2013), scrutiny starts in the upper-right corner. A tabbed line, reminiscent of a flagged ribbon or a plan of suburban subdivisions, begins in pure black before it rolls off in brushy plums and jade greens. But from here, all bets are off. Von Heyl’s imagery prompts flashes of recognition—in a harlequin-esque form or a humorous suggestion of an armadillo. At last, the iridescent puzzle-piece layer reveals itself. When we ask what was painted first, we are denied an answer, instead left to ponder myriad possibilities. Such curiosities, erasures, flippant flicks of the brush that are anything but carefree, are the traces of the energetic process that von Heyl enacts each time she comes before a large blank canvas.

Von Heyl has described standing in her studio with a row of vast white surfaces before her, a smorgasbord of infinite possibilities, and the mettle it takes to make that first mark. Looking at her works, one imagines the relief von Heyl must feel when the pristine canvas is no longer screaming and she is able to focus on how to make a painting—what it is to contend with a history so large—in an effort to articulate a space for herself. Over and over again, von Heyl claims space for her works. She refuses definition, categorization, and even too much self-reference (though there is some); she denies our desire for the known, yet she does not embrace the truly unknown either. Von Heyl’s works, her paintings especially, hover on the precipice of recognition, but they do not take sides.

--Abigail Ross Goodman