Art Since 1950

Contemporary art is essential to the mission of a teaching art museum; it is the art that reflects our current reality, interprets our history, informs and molds us. Importantly on a college campus, contemporary art embodies interdisciplinary thinking and teaches about literacy, cultural currencies, and the interface of the creative process with socio-political and ethno-religious issues. At RMA, the contemporary art collection has experienced the most rapid growth over the last several years, starting with the creation of the Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art at Rollins College (one of our Featured Collections) in 2013. Due to the extraordinary generosity of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, this collection – now including more than 400 works – continues to grow. In parallel, other acquisitions address other areas of the contemporary art landscape, allowing our museum to be an active participant in the dialogue about the art of today and showcase art as an agent of change.

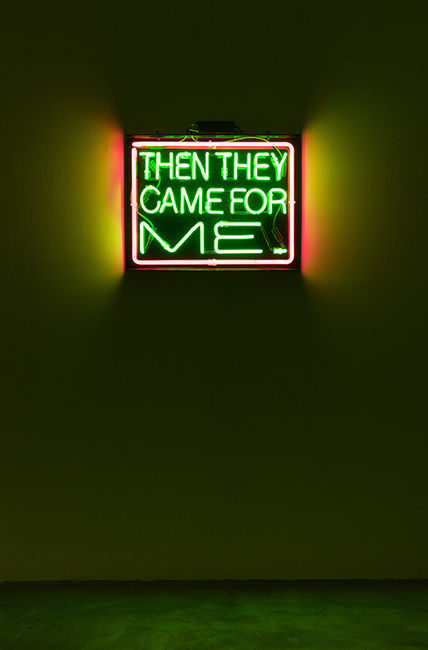

Contemporary art is an area of top priority for ongoing acquisitions. In recent years, we have intentionally focused on strengthening our holding by women and minority artists, especially African-American and Latino artists, offering diverse perspectives and approaches that reflect a multitude of experiences throughout our cultural history. Significant acquisitions include sculptural works by Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012), Whitfield Lovell (b. 1959), and Rina Banerjee (b. 1963); paintings by Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000) and Ria Brodell (b. 1977); prints by Luis Camnitzer (b. 1937) and Jay Lynn Gomez (b. 1986); and a neon sculpture by Patrick Martinez (b. 1980).

PLEASE NOTE: Not all works in the Rollins Museum collection are on view at any given time. View our Exhibitions page to see what's on view now. If you have questions about a specific work, please call 407-646-2526 prior to visiting.

Artists Featured in This Section

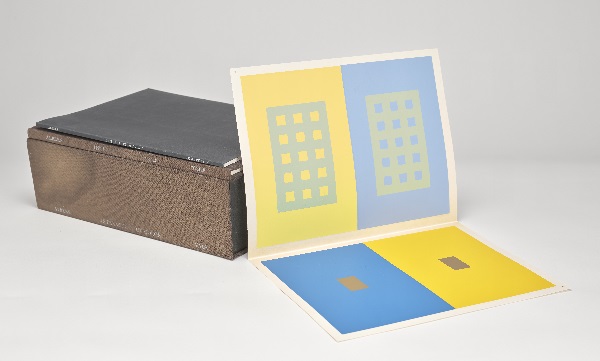

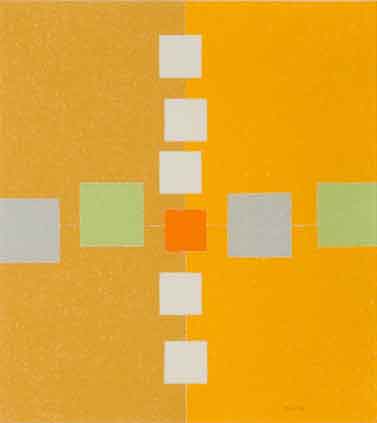

Josef Albers

(American, 1888-1976)Homage to the Square, SP-VII, 1967

Silkscreen, sp viii, 53-125

Museum purchased from the Wally Findlay Acquisitions Fund 1990.6 © The Anni and Josef Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York, NY

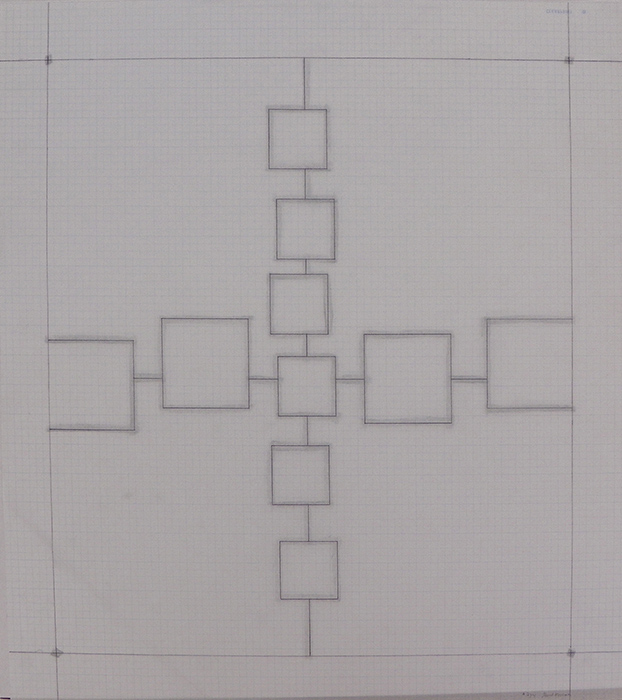

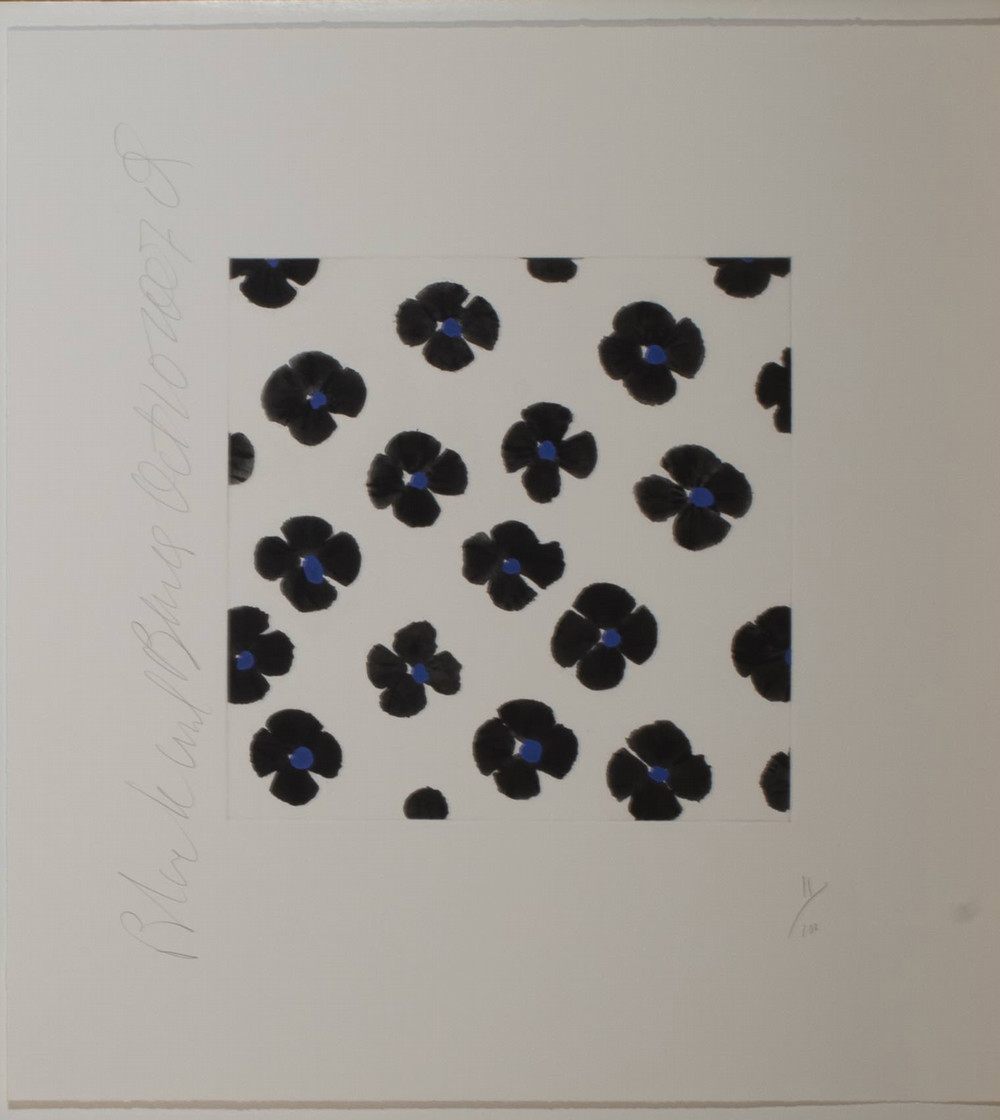

Inspired by his long career as an educator and artist, Albers began the series Homage to the Square in 1948 while working at Black Mountain College, a radically experimental liberal arts college in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Western North Carolina. Believing that students could only understand artistic form through close observation and repetition of its individual elements, Albers encouraged his students to carefully examine the relationships between and among colors, lines, and other pictorial elements. This practice inspired his own work, resulting in the long-running series of paintings and silkscreens, which he continued after taking over the Department of Design at Yale, and after retiring from teaching in 1958.

First published in a portfolio of 12 in 1967, in 1972 Albers included this print in Formulation: Articulation, a series of prints which he felt encapsulated the entirety of his career. Despite his advanced age (he turned 84 in 1972), Albers supervised the printing at Ives-Sillman, which was run by two former students of his and which also printed Interactions of Color, his 1963 distillation of his ideas about color and its study and uses. These works, which the artist and critic Elaine de Kooning said could have come from no other artist, are indicative of his personality, which was both exacting and experimental, systematic and spontaneous.

Josef Albers

(German American, 1888-1976)Interaction of Color, 1963

Silkscreen

14 1/2 in. x 11 in. x 5 in.

Gift of William L. Whitney, 2002.3 © 2022 Josef Albers/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Lynn Aldrich

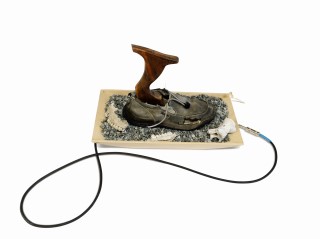

(American, b. 1944)Pressed for Time, 1994

Ironing board, waxed paper, collected flowers, wood

35 x 53 x 14 in.

Gift of Peter Norton, 2016.16.1 © Lynn Aldrich

Taught to make keen observations on her surroundings by her research scientist father, Lynn Aldrich was raised to have an appreciation for science and the natural world. Though she received a BA in English and later an MFA in painting, Aldrich found her calling in the sculptural arts. Inspired by the revolutionary “ready-made” art of Marcel Duchamp, Aldrich’s work focuses on taking common household items and placing them in uncommon environments to be assessed as art. Though the items Aldrich chooses for her art inevitably possess certain connotations in the minds of viewers, Aldrich plays on these preconceived notions to inspire new ways of thinking about objects. Including an ironing board topped with pressed flowers, Pressed for Time invites us to reflect on the function of these objects and how they relate to the interactions between humans and nature.

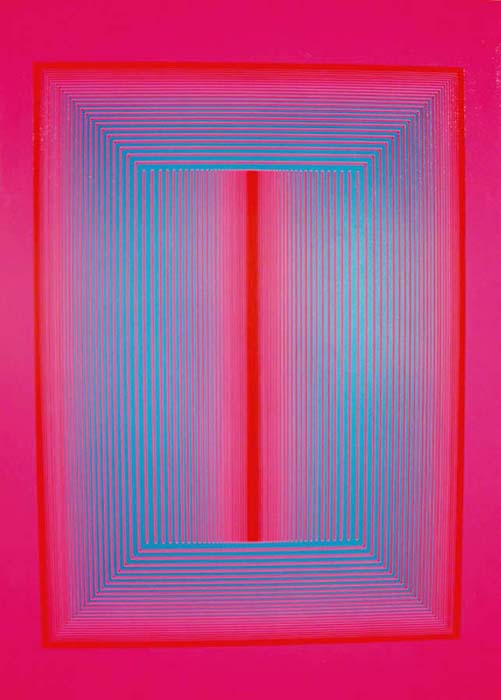

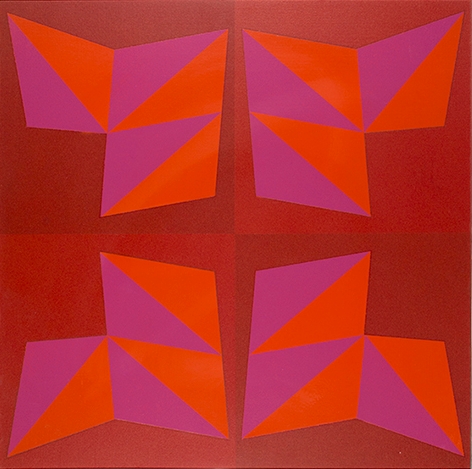

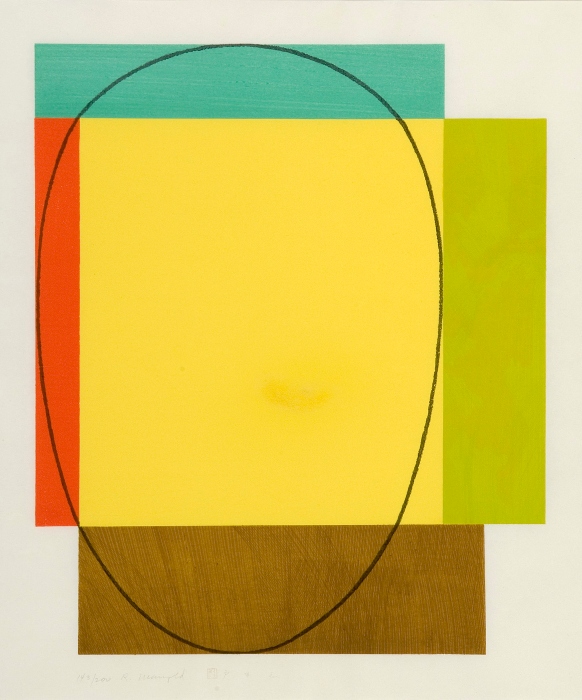

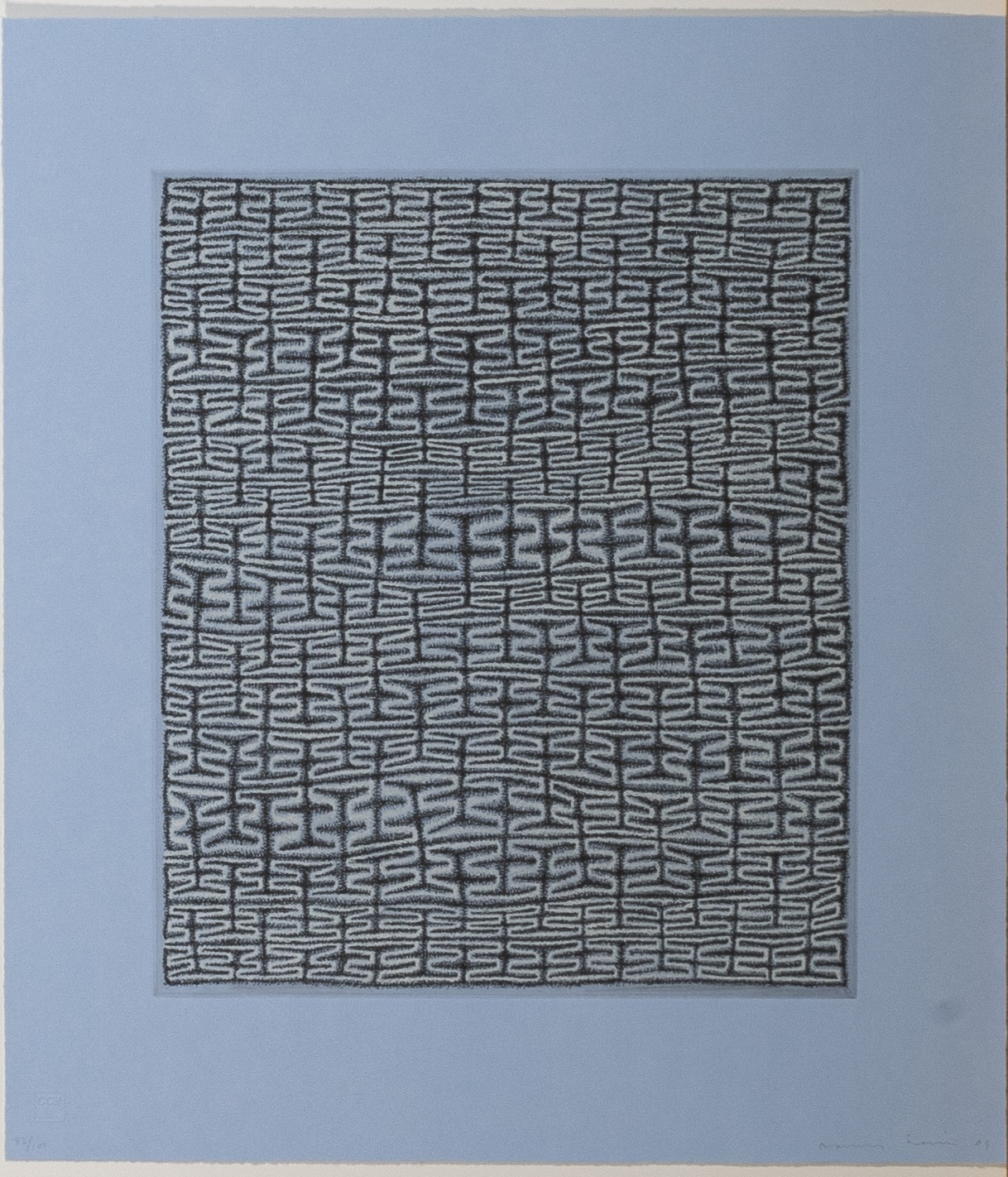

Richard Anuszkiewicz

(American, 1930-2020)Reflection VII-Red Line, 1979

Silkscreen and acrylic on masonite

64 1/2 in. x 47 in. print

Gift of Charlotte Colman © Richard Anuszkiewicz/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 1990.18

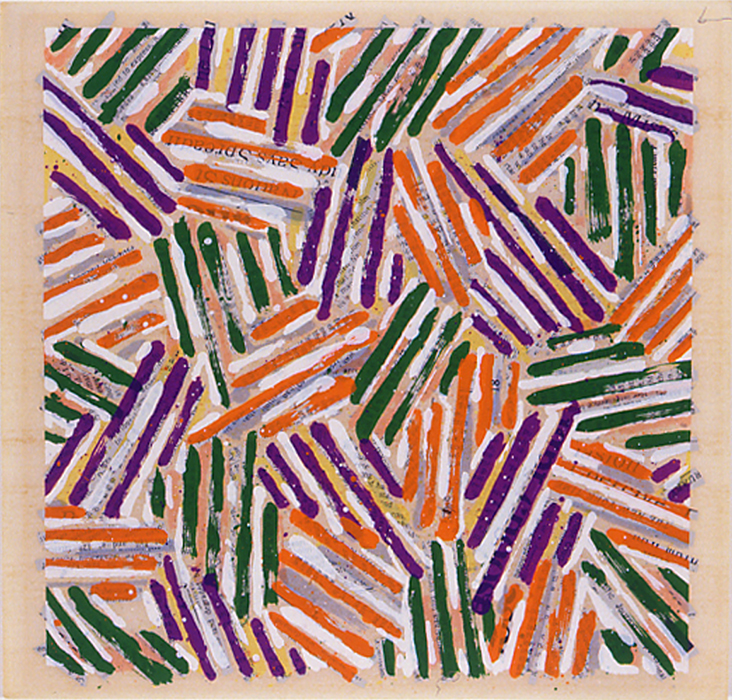

Part of a generation of artists who came of age during the peak of Abstract Expressionism in the United States, Richard Anuszkiewicz eschewed the painterly, gestural style of that movement while embracing its interest in all-over compositions executed in large scale with bright acrylic paints. He was heavily influenced by his mentor Josef Albers, with whom the studied at Yale University, embracing the older artist’s interest in the relationships between colors, especially when rendered in precise, geometric shapes. Anuszkiewicz took up printmaking in the early 1960s, and like many artists of his generation originally viewed it as a means of reproducing his paintings in smaller and more accessible formats. He quickly realized the possibilities for further color experimentation inherent in lithography and silkscreen, however, and embraced printmaking as a core part of his artistic practice.

This print, one of a series of Reflections executed in 1979, is the result of a particularly fruitful period of experimentation Anuszkiewicz began in the mid-1970s. Silkscreen—in which pigment is forced through a mesh screen onto paper or other substrate—allowed him to make particularly large prints, especially when printed onto Masonite, a sturdy type of composite wood. Anusckiewicz began printing these works as many as four times, creating thick buildups of color. These objects, with their size and paint-like surfaces, approach the status of painting-print hybrids, creating hard-edged yet luminous surfaces that minimize their own objecthood, instead emphasizing the environmental impact of all that color.

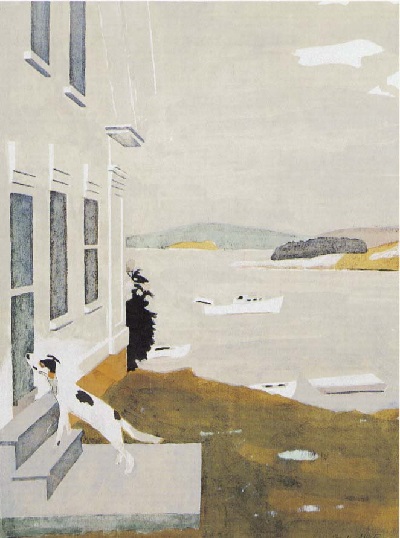

Milton Avery

(American, 1885-1965)Pelican, 1951

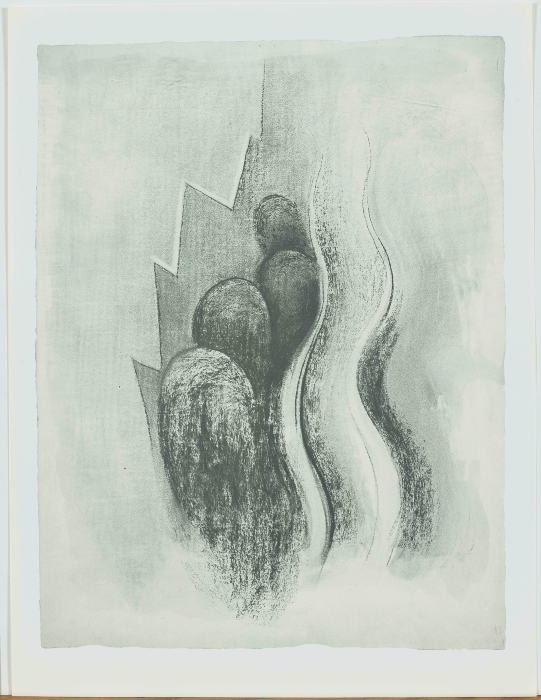

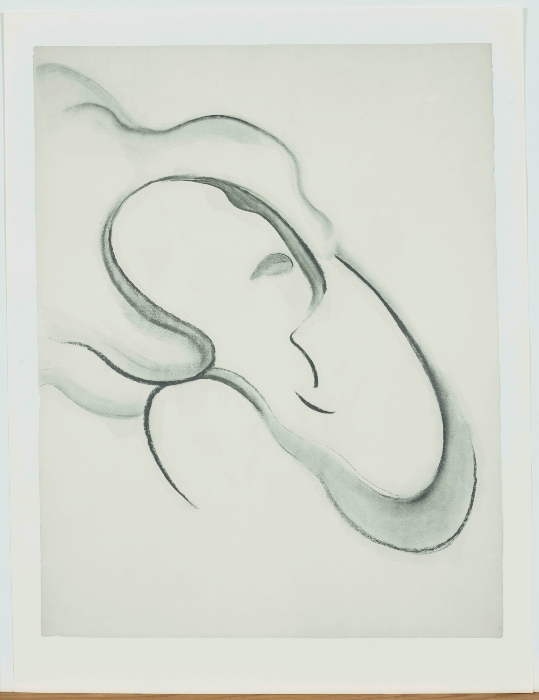

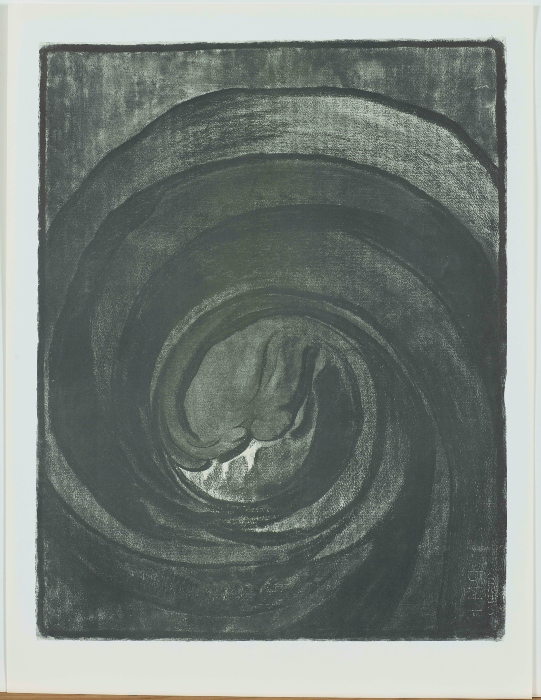

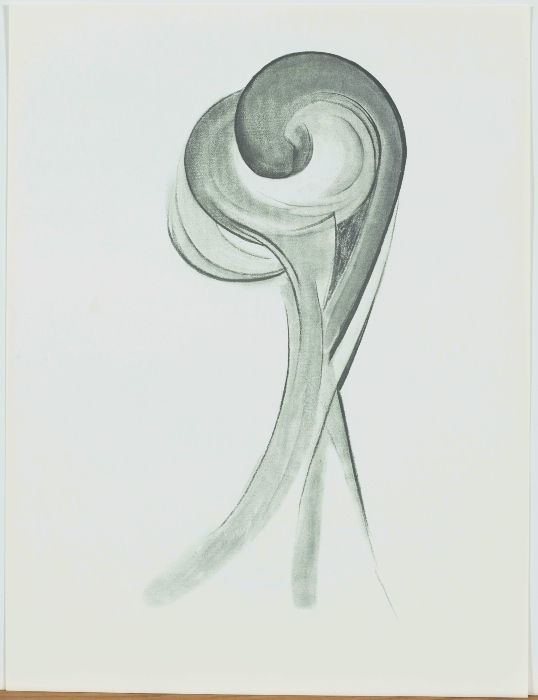

Monotype

18 in. x 24 in.

Gift of the Milton Avery Trust, 1998.11 © The Milton Avery Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York, NY

Hailing from a working-class family, Milton Avery was the sole breadwinner for his mother and sisters starting at age twenty, working a variety of blue-collar jobs at night, leaving him time to study art during the day. It was only at age forty when he and his wife Sally moved to New York, where Avery was exposed to European and American modernism for the first time, that he devoted himself to his art full time. Sally’s work as an illustrator enabled him to focus on painting, and he developed a unique style that blended French Fauvism, American folk art, and his interest in the luminous possibilities of paint. Out of step with the social realism that dominated in the 1920s and 1930s, Avery’s thinly painted style and careful experimentation with color had a strong influence on Adolph Gottlieb, Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko, and other younger Abstract Expressionist painters whom he befriended in the 1940s.

This print was made in 1951 while Avery was in summer residence at The Research Studio in Maitland. Too weak to paint due to a recent heart attack, he instead explored the possibilities of monotype, a printmaking method in which ink or other media are applied directly to the printing surface, in this case glass. Using a sponge, he wiped the ink on the surface, creating thinly luminous bands of color that allowed the white of the paper to show through. This practice was hugely influential on his later painting, as he began to use sponges to apply his paint while also simplifying his forms. In this work as in other frequent representations of both birds and the sea, Avery evokes the sense of yearning alienation that he felt was a core aspect of the experience of modern life.

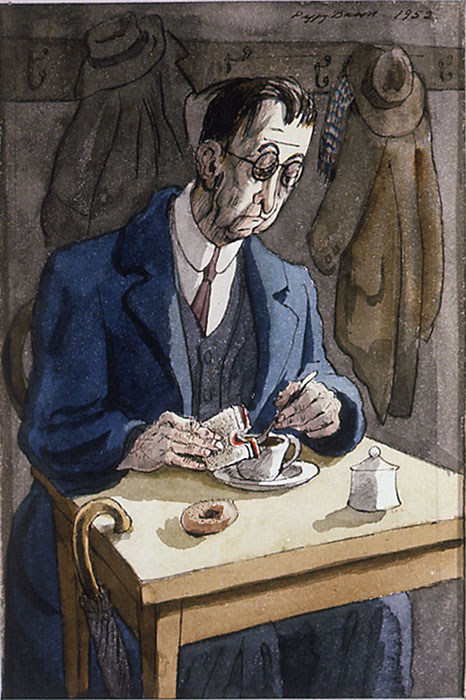

Peggy Bacon

(American, 1895-1987)Lamentable Lunch, 1952

Gouache on Paper

7 ½ in. x 5 in.

Gift of Anne M. Farr. 1997.7

Peggy Bacon, born to artist parents, followed in their footsteps by attending the Art Students League in New York during its heyday, where she studied with George Bellows, John Sloan, and other American realists. Though she trained as a painter, her earliest work was in drypoint, a printmaking medium in which the painter scratches a design directly on a metal plate with a specialized needle. During the 1920s and 1930s she turned to oil pastels, using them to execute a series of caricatures of her contemporaries in the New York art and intellectual worlds. These pastels, which demonstrate her flair for witty exaggeration, brought her a great deal of fame as they were published in The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, and other widely read magazines. She was also a prolific illustrator of books.

After about 1945, Bacon began to return to painting, working mostly in gouache in the 1940s and 1950s before returning to oils in her last years. Lamentable Lunch is a fine example of her gouache work, which turned from caricature to subtler—though still wittily ironic—portraits of everyday Americans. This painting demonstrates her mastery of the medium, a kind of opaque watercolor, as she uses her sweeping brushstrokes and fine eye for color to show an office worker eating a hurried meal of coffee, donut, and jelly sandwich, seemingly crammed into a café’s coat room. Bacon’s eye for everyday detail and sly sense of humor remained a constant throughout her career.

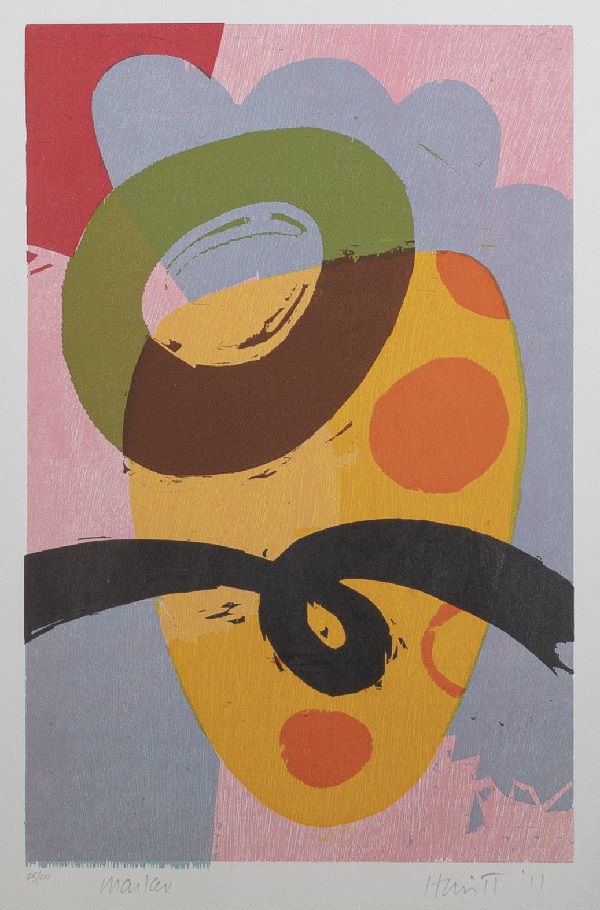

Myrna Báez

(Puerto Rican, 1931-2018)Pausa, 1989

Color Serigraph

41 ½ x 29 ¼ in.

Gift from the Collection of Benjamin Ortíz and Victor P. Torchia Jr. 2022.4 © Estate of Myrna Báez González

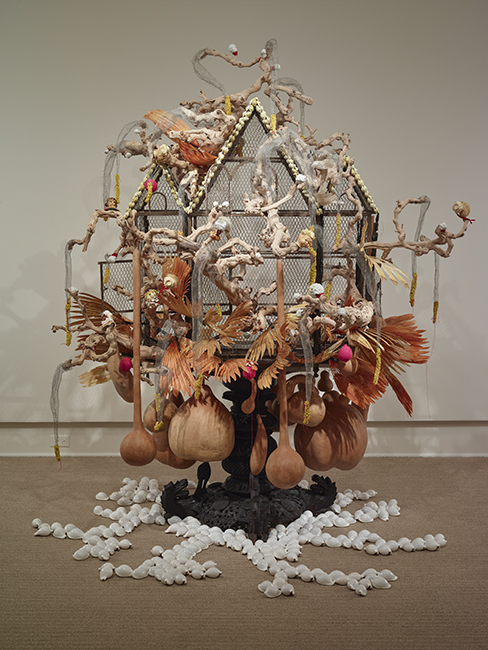

Rina Banerjee

(American, b. Kolkata, West Benghal, India, 1963)Her captivity was once someone's treasure and even pleasure but she blew and flew away took root which grew, we knew this was like no other feather, a third kind of bird that perched on vine intertwined was neither native nor her queens daughters..., 2011

Anglo-Indian pedestal 1860, Victorian birdcage, shells, feathers, gourds, grape wine, coral, fractured charlotte doll heads, steel knitted mesh with glass beads

83 7/8 x 83 7/8 x 72 in

Museum purchase from the Michel Roux Acquisition Fund, 2016.20

With her organic, carefully orchestrated sculptures, Rina Banerjee reveals a migration of ideas and cultural symbols. She interrogates historic objects— where they come from and the stories they can tell—in her distinctive works. In conceiving this work, the artist focused on domestic slavery. A Victorian birdcage, shaped like a large home, forms a central part of the composition. Birdcages reoccur across Bannerjee's diverse works. Here, the cage remains open, giving a sense of flight; the captive has fled bondage. Various meanings are assigned to objects by their creators and their owners. Banerjee ponders the value of goods and their perceived worth. Here, the prominent orange feathers were purchased from a website promising “authentic Asian goods,” while the large and whimsical gourds were grown locally in Florida and purchased on the land where they were harvested. In this work, Banerjee navigates the tension between the local and the global, and the notion of authenticity is explored and deconstructed. While the artist is interested in the movement of goods and people, her sculptures, like this one, testify to a migration of ideas as well. This work in particular is significant in her oeuvre not only for the ideas it imparts, but for its noteworthy presentations.

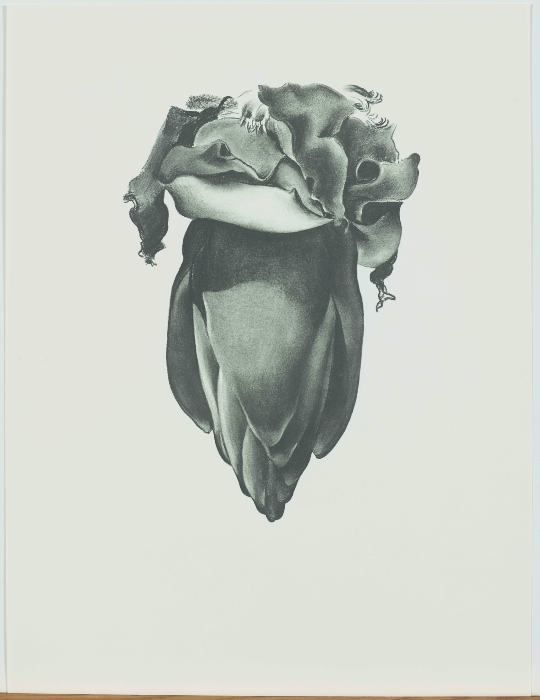

Leonard Baskin

(American, 1923-2000)Rat, ca. 1965

Ink

9 5/8 x 15 3/8 in.

Gift of Mr. Ralph E. Kaschai, 1979.24

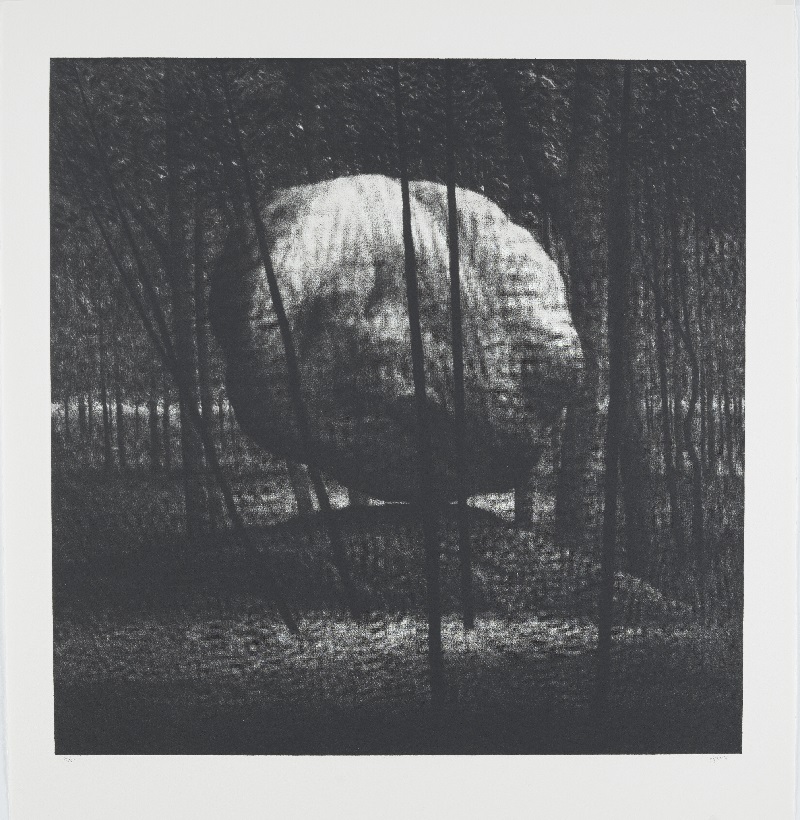

Leonard Baskin was in many ways a man out of step with his times. Raised in a religious Jewish household in New Jersey and Brooklyn, Baskin was possessed throughout his career with a sense of the potential for apocalyptic doom latent in the human condition. Though he first came to prominence during the time of Abstract Expressionism, when artists eschewed the figurative and embraced new techniques and synthetic media, Baskin was a resolute traditionalist. Unlike many artists of his generation, he trained in Europe as a sculptor and printmaker, and preferred working with ancient materials like wood, copper, and ink over the bright acrylics embraced by his contemporaries.

In his drawings and prints Baskin often created grotesque human and human-animal hybrids, often diseased or in states of decay, a reflection of his preoccupation with the potential in humanity for moral decay. This ink drawing depicts a massive, distended rat, the dark washes of ink bleeding over the sketchily outlined form. The blackness overwhelms the tiny head, blotting out the creature’s eyes and blurring the line between life and death. Moving away from the head, the ink smears first to gray and then to white, which stands out against the creamy beige of the paper. This transition from black to white suggests something of a Manichean struggle between light and darkness, good and evil.

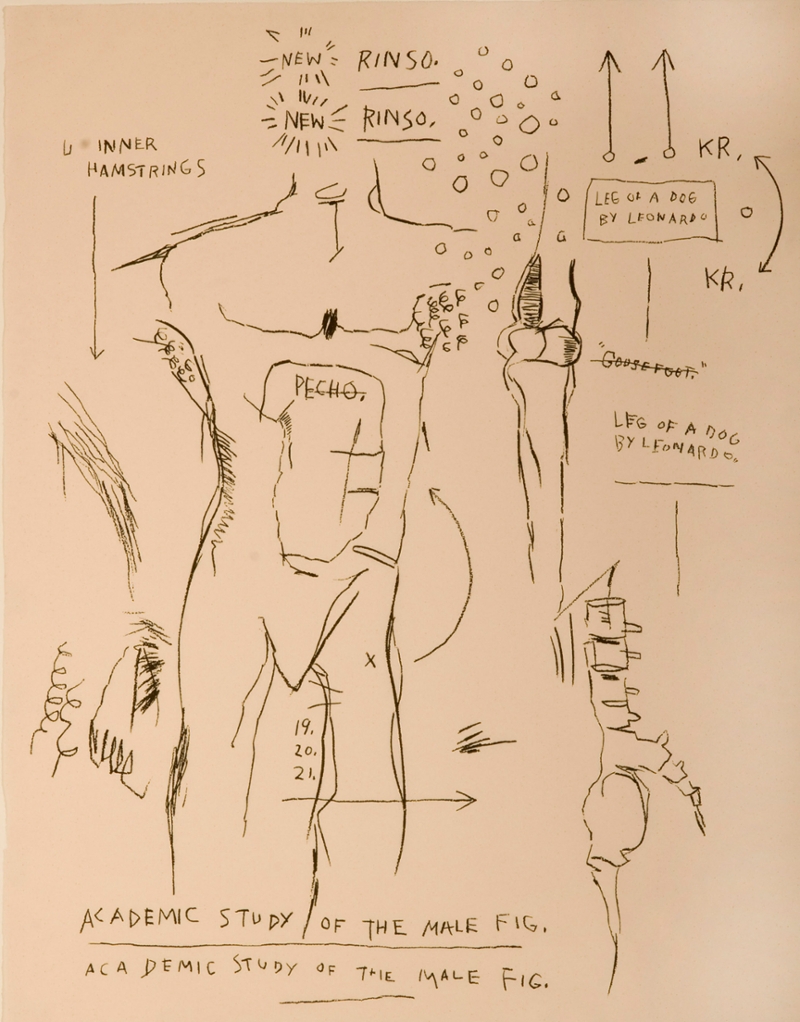

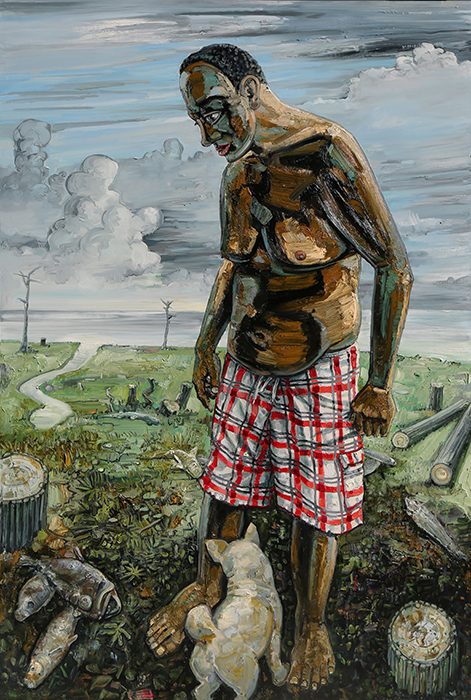

Jean-Michel Basquiat

(American, 1960-1988)Academic Study of the Male Figure, 1983

Brown screenprint on Okiwara paper

31 1/4 x 39 3/4 in.

Museum Purchase from the Michel Roux Acquisitions Fund, 2007.14

Internationally-renowned American artist, Jean-Michel Basquiat, defined his career through his works in painting and print. He often drew inspiration from his personal Puerto Rican and Haitian heritage. At the age of eight, Basquiat was hit by a car and suffered from several broken bones and internal injuries. While he was healing, his mother gave him the medical textbook Gray’s Anatomy. This period of trauma and recovery had a lasting effect on the artist, and the anatomical drawings found within the textbook served as early references for Basquiat’s later works. This work builds on that influence while it simultaneously recalls Leonardo da Vinci’s human anatomy studies. Basquiat’s work is often associated with the Neo-Expressionism art movement, in which the importance of the human figure was reasserted into the canon of contemporary art with a focus on emotion and subjectivity.

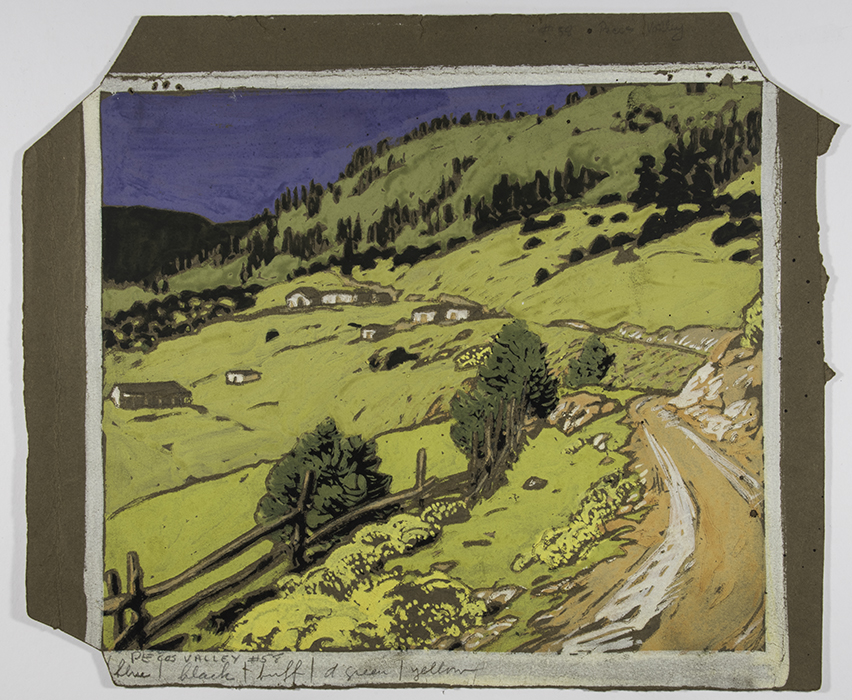

Gustave Baumann

(American, 1881-1971)Pecos Valley (drawing), ca. 1920

gouache and graphite on brown wove paper

11 1/2 in. x 13 1/4 in. print

Gift of the Ann Baumann Trust, 2013.35.1 © Ann Baumann Trust

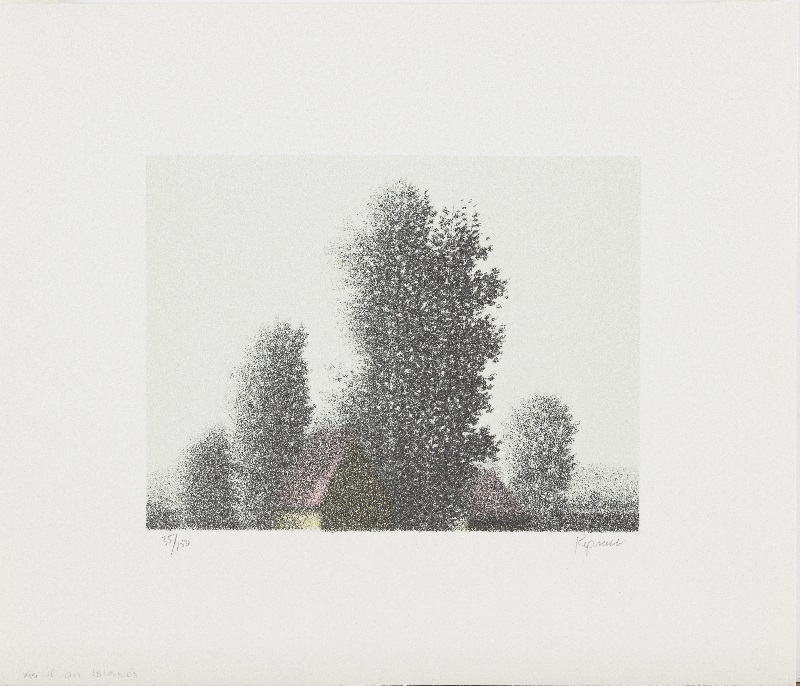

Gustave Baumann immigrated to Chicago with his family when he was ten. The oldest of four children, he was forced to assume financial responsibility while still a teenager after his father abandoned Baumann, his mother, and siblings. He quickly found work in a variety of Chicago engraving shops, showing a facility for printmaking that led him to a successful career as a commercial illustrator with a particular specialty in package design. The year 1904 was a particularly auspicious one for Baumann, as he became a United States Citizen, using his newfound passport to travel back to Europe—specifically Munich—to study. In Germany, he immersed himself in the Jugendstil and Vienna Secession outgrowths of the Art Nouveau style he already favored, as well as further studying the Japanese wood block printing technique known as ukiyo-e.

Upon his return to the United States, Baumann resumed his career as a commercial artist while also setting aside time for artistic printmaking. He eventually relocated to Brown County, Indiana, some 230 miles south of Chicago and the site of an art colony surrounding the Hoosier School painter T.C. Steele. In 1918, after a year or so bouncing around New York State, Baumann visited New Mexico, making stops first in Taos and then Santa Fe, where he visited an exhibition of his prints. He ended up staying for the rest of his long life, becoming a fixture of the Santa Fe art scene while producing brightly colorful wood block prints of the stunning countryside of the Southwest.

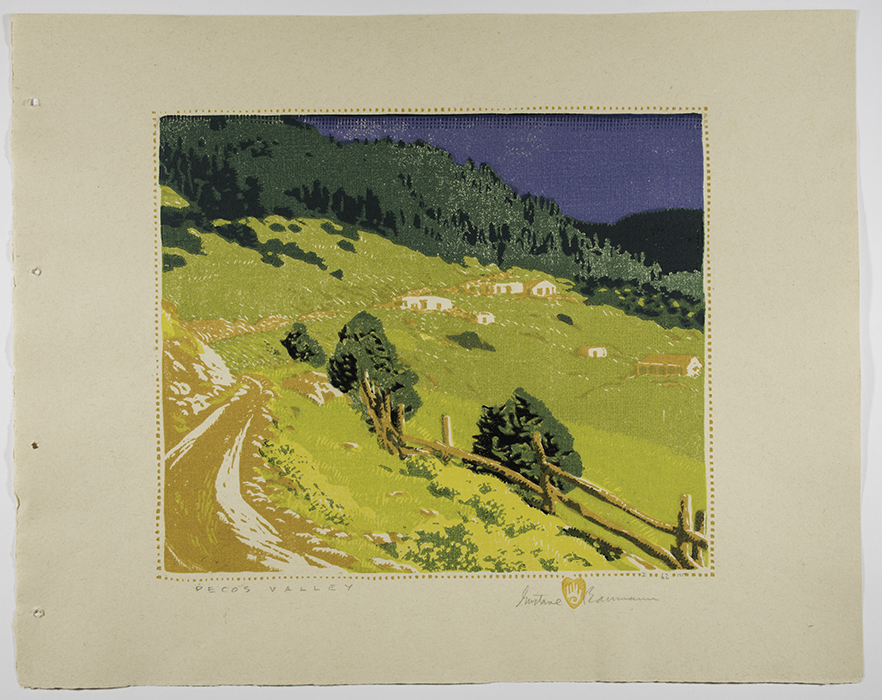

Gustave Baumann

(American, 1881-1971)Pecos Valley (finished proof), 1921

Ink on Cream Zanders laid paper

13 1/2 in. x 17 in. print

Gift of the Ann Baumann Trust, 2013.35.2 © Ann Baumann Trust

Baumann based his prints on preparatory drawings and egg tempera sketches which he made on-site. Returning to his studio (which he called his workshop), he carefully carved a block of basswood—also known as linden—for each color in the finished composition, being careful that each block lined up precisely with the others to avoid blurring the final print. He worked with the same old-fashioned hand press—purchased in 1917—for his entire career. A perfectionist, he experimented with a variety of papers and inks, continually refining the mixtures of pigments, solvents, and fixatives in order to ensure durability, evenness, and luminosity of color. He also printed from dark to light—the reverse of the usual process—allowing him more subtle layering effects but vastly increasing the difficulty of ensuring everything lined up properly. As a result of his exacting nature, Baumann’s wood blocks were so carefully carved that they were often exhibited alongside the finished prints. His daughter, Ann, has maintained this tradition by ensuring that the blocks—as well as progressive proofs demonstrating their use—remain together in museum collections around the country.

This print depicts the Pecos River, which originates in Northwest New Mexico and flows south through West Texas, eventually emptying into the Rio Grande. In Baumann’s time the area was sometimes referred to as the American Tyrol, after the Alpine region of Italy and Austria. Baumann represents a lush mountainside dotted with the buildings of a small town, or perhaps a ranch. His use of a rich golden yellow—indicated as buff in a note on the tempera drawing—gives the scene a bright, luminous quality that contrasts with the darker tones of the trees, sky, and distant mountains.

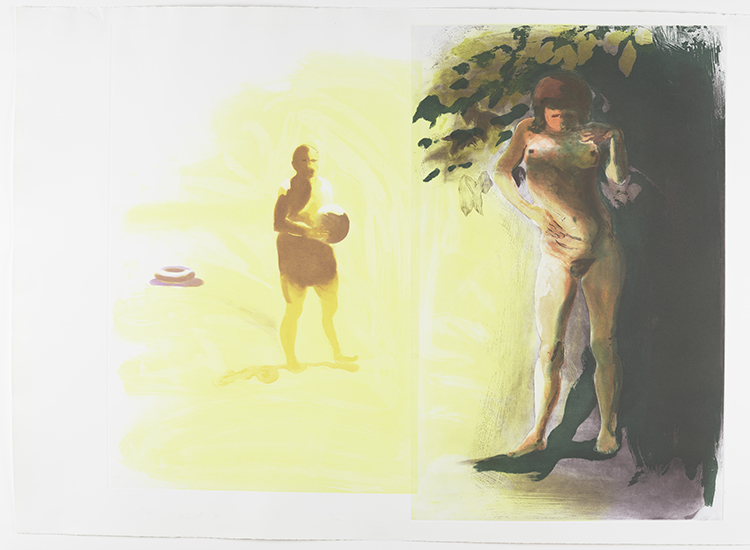

Romare Howard Bearden

(American, 1911-1988)In the Garden, 1979

lithograph

28 3/4 x 21 1/8 in.

Gift of Mr. Saul Taylor, 1980.31.1 © 2023 Romare Bearden / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

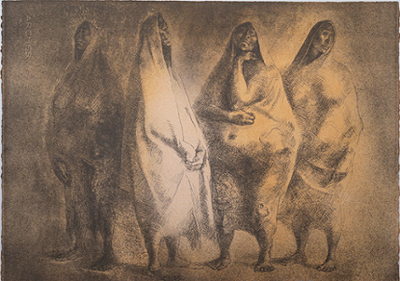

Romare Bearden experienced the Great Migration—the decades-long movement of African Americans from the Jim Crow South to Northern cities—at a young age, when he moved with his parents from Charlotte, North Carolina to Harlem in New York City. During his childhood he spent time in Pittsburgh and the suburbs of Baltimore, two additional centers of Black life, but otherwise was a lifelong New Yorker. Nonetheless, he made frequent visits to Charlotte and other areas of the South to visit family, and the Black culture of the South informs much of his artistic production.

Bearden’s best known works blend Cubist collage practices with imagery taken from African and African Diaspora art and culture, and his collages and related works frequently feature conjur (Bearden’s preferred spelling) women, privileged members of the community who used African magical and ritual techniques passed down through the generation. For Bearden, conjur women symbolized and called forth a cultural space uninflected by racism, segregation, and other forms of prejudice. This lithograph, which draws much of its imagery from a collage and silkscreen of the same name, calls forth that tradition while also celebrating the beauty and fecundity of the South.

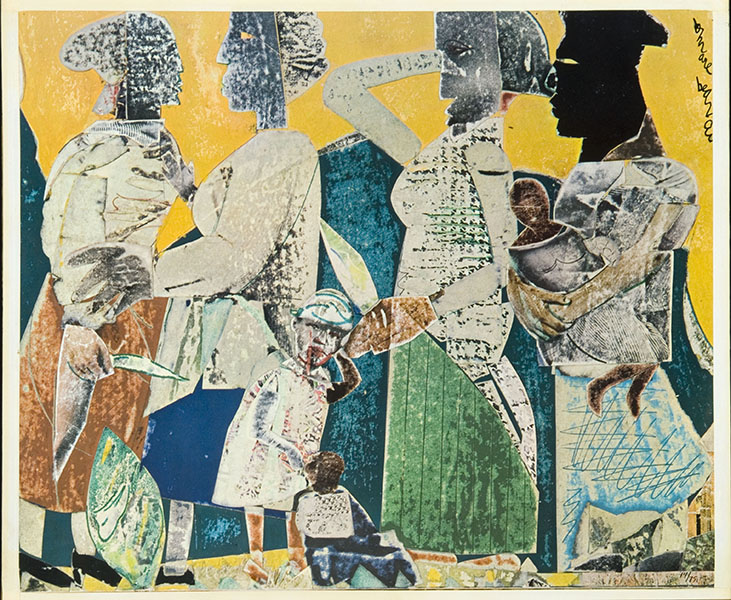

Romare Howard Bearden

(American, 1911-1988)Ritual Bayou (from the series Ritual Bayou), 1971

lithograph collage

15 1/8 x 21 1/8 in.

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert L. Gardner, 1983.34.1 © 2023 Romare Bearden / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Romare Bearden was a successful member of the New York art world from the 1930s to the early 1960s, when he first adopted the collage aesthetic for which he is known today. Early in his career he worked in a figurative style influenced by Mexican Muralism before moving towards abstraction during the heyday of Abstract Expressionism. He always felt a tension between his intense interest in the history of art and his desire to make work that was politically and socially relevant to his experience as an African American living in the United States. Inspired by the Civil Rights Movement, he began to experiment with collage, which proved to be the perfect medium to unite these two interests. Collage was important to Cubism and Dada, two avant-garde movements with explicitly social consciences, and it gave him a new vocabulary with which to depict both the joyous and sorrowful elements of the Black experience in the United States.

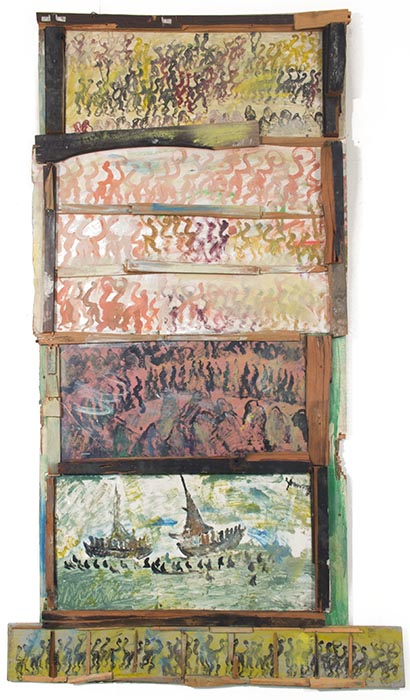

These lithographs, published in 1971 as part of a collaboration with Shorewood Publishers in New York, are all based on foundational collage works shown at his 1971 Museum of Modern Art exhibition. As with most of his printmaking practice, Bearden worked closely with Shorewood’s master printmaker, first using transfer paper to put the image onto a metal lithography plate, then putting in color and details by hand. After printing, he carefully reviewed each proof, returning to Shorewood to make changes until he was satisfied with the finished product. The result was a print that retained some of the handmade qualities and imagery of the collages while also standing alone as an original work of art. The name of the portfolio—Ritual Bayou—thus indicates the centrality of both African American cultural life and the process of iteration in Bearden’s work.

Romare Howard Bearden

(American, 1911-1988)Byzantine Frieze (from the series Ritual Bayou), 1971

lithograph collage

17 7/8 x 21 1/4 in.

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert L. Gardner, 1983.34.2 © 2023 Romare Bearden / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

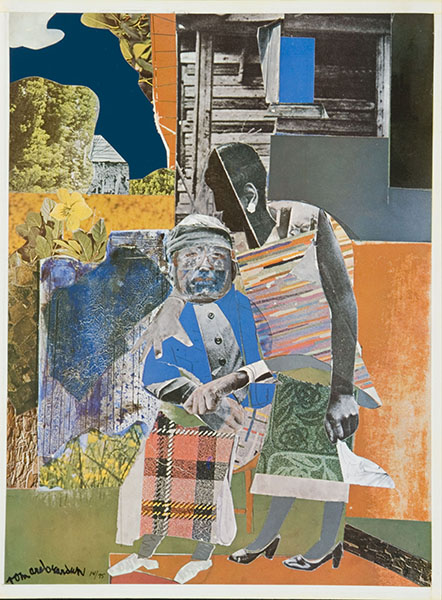

Romare Howard Bearden

(American, 1911-1988)Mississippi Monday (from the series Ritual Bayou), 1971

lithograph collage

16 1/2 in. x 21 1/4 in.

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert L. Gardner, 1983.34.3 © 2023 Romare Bearden / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Romare Howard Bearden

(American, 1911-1988)Memories (from the series Ritual Bayou), 1971

lithograph collage

15 1/8 x 21 1/8 in.

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert L. Gardner, 1983.34.4 © 2023 Romare Bearden / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In 1914, the young Romare Howard Bearden and his family emigrated from his native Charlotte, North Carolina to Harlem, New York during the movement known as the Great Migration. Living within the atmosphere of the culturally vibrant Harlem Renaissance, Bearden began creating art as an outlet for the expression of Black life. Though his career as an artist and activist thrived in New York, he reminisced on his childhood in the South, contemplating the relationship he and other Black people had with that context. Part of the series Ritual Bayou, Memories conveys the artist’s deep appreciation towards the North Carolinian landscape and its people. Using a collection of found images of birds, plants, and other natural symbols, Bearden incorporates the image of a female figure amongst the lush scenery. The combination of both human and natural elements conjures Bearden’s memories of life in the South.

Romare Howard Bearden

(American, 1911-1988)Carolina Interior (from the series Ritual Bayou), 1971

lithograph collage

18 x 21 1/4 in.

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert L. Gardner, 1983.34.5 © 2023 Romare Bearden / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Romare Howard Bearden

(American, 1911-1988)Reunion, 1971

lithograph collage

21 1/4 x 16 1/2 in.

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert L. Gardner, 1983.34.6 © 2023 Romare Bearden / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Romare Howard Bearden

(American, 1911-1988)Odysseus; Fall of Troy, 1979

Color screenprint on wove Lana paper

17 7/8 in. x 23 7/8 in.

Museum Purchase from the Wally Findlay Acquisition Fund, 1992.12 © 2023 Romare Bearden / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Rosemarie Beck

(American, 1923-2003)Phaedra and Hippolytus, 2002

Oil on Canvas

17 5/8 x 20 1/8 in.

Gift from Betty L. Boer Franklin, 2019.6 © Rosemarie Beck Foundation

The child of Hungarian immigrants, Rosemarie grew up studying music, theater, and art history, majoring in the latter at Oberlin College. Except for a year spent at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, she did not study painting formally. A summer spent in Woodstock, New York just after her marriage brought her into contact with Bradley Walker Tomlin and Philip Guston, two of the rising generation of painters that would become known as the Abstract Expressionists. Under their tutelage—including a summer spent working in the Woodstock studio of Robert Motherwell—Beck developed her own Abstract Expressionist style based on the careful application of small lozenges of deep, luminous color. These works soon earned her acclaim as one of the notable figures in the second generation of the movement, including favorable reviews in both the artistic and mainstream presses.

Beck, however, could not shake the feeling that she was a figurative painter at heart, and she renounced her former abstraction at the end of the 1950s, embarking on a series of works indebted to Ovid, Shakespeare, and other canonical literary figures. She began to create groups of closely related works on these subjects while retaining her careful yet painterly style. Around the same time, she began a long career as a teacher, advocating tirelessly for the vitality of figurative art during a time when the art world was preoccupied with abstract and conceptual modes. The subject of Phaedra preoccupied her last years, in particular after her diagnosis with an inoperable brain tumor ended her teaching career. The story—of a woman who tragically and disastrously falls in love with her stepson before dying by suicide—seems to have allowed Beck to work through images of death as she herself lived out her last months.

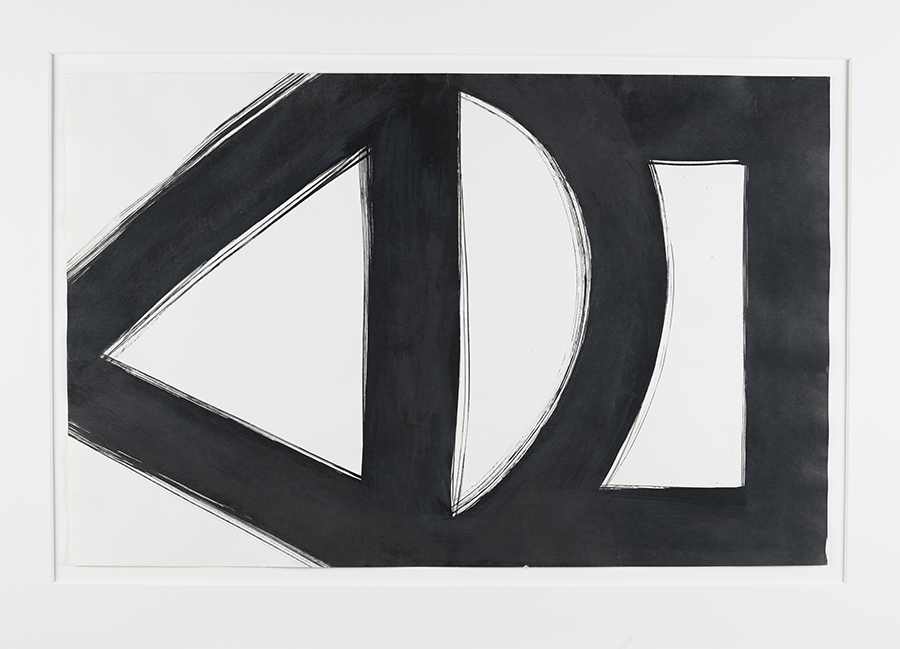

Trevor Bell

(British, 1930-2017)Split Painting, 1980

Acrylic on canvas

84 x 84 in.

In Memory of Dr. Rita Bornstein, President, Rollins College, 1990-2004. 2024.2. © Estate of Trevor Bell, Courtesy Waterhouse & Dodd

British abstract artist Trevor Bell had a strong connection to Florida. Born in 1930, Bell moved to Tallahassee where he taught art at Florida State University for more than twenty years. His canvases are characterized by a colorful exuberance that gives form to imperfect yet sumptuous shapes. This painting, created during Bell’s time in Florida, is divided in two horizontal registers; the green and blue perimeter shapes almost connect but not quite, leaving areas where the purple and pink background moves forward. Bell’s approach to painting prioritized shape, color, and structure over narrative. However, his experience of the Florida landscape encouraged him to experiment and push the boundaries of abstraction: “I opened up and began using intense colors that I’d never used before. I called the paintings heatscapes.”

Dawoud Bey

(American, b. 1953)Janice Kemp and Triniti Williams, 2012

Archival pigment prints mounted on dibond

40 x 64 in (40 x 32 in individually)

Museum purchase from the Kenneth Curry Acquisition Fund, 2015.9., Image courtesy of the artist and Rena Bransten Gallery

From his early street photography made in Harlem, New York City, to his iconic portraits of high-school students, Dawoud Bey creates emotive pictures of humanity. Bey’s pictures inspect and reflect upon the notion of place, which is a central thread in the Birmingham Project, of which the work here is a part. On the morning of September 15, 1963, four African American girls were killed when Ku Klux Klan members bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. Later that same day, two African American boys were killed in separate incidents as a result of racial violence. To recognize these horrific tragedies on their 50th anniversary, Bey created a series of diptychs of residents of the city. He identified young people who were the ages of the victims and then found adults who were approximately the ages those victims would have been if they had lived. He juxtaposes the adults and youth in black-and-white photographs taken in the Bethel Baptist Church in the city's Collegeville neighborhood, chosen for its role in the Civil Rights Movement, and in the Birmingham Museum of Art. The subjects here, as they do across the entire series, look directly at the viewer, an exchange of gaze that heightens the emotional intensity of the work. Though photographed separately, they are paired together through their individual yet parallel poses. Separated across generations, they are united in their resilience and recognition of the terror and tragedy of September 15, 1963.

Gary Bolding

(American, b. 1952)Big Gulp Altarpiece - Triptych, 2003

Oil on panel

15 1/2 in. x 44 in.

Museum purchased from the Cornell Anniversary Acquisitions Fund, 2003.9 © Gary Bolding

Mark Bradford

(American, b. 1961)Life Size, 2019

Cast handmade cotton paper, pigment, gouache, ink, letterpress

12 x 9 x 1 in.

Gift of Benjamin Reed Hunter, 2022.35 © Mark Bradford

Matthew Brandt

(American, b. 1982)Long Lake, WA 2, 2012

C-print soaked in Long Lake water

30 in. x 38 1/2 in.

From the series "Lakes and Reservoirs." Museum purchase by the Cornell Contemporaries, 2013.36 © Matthew Brandt

Matthew Brandt developed the photograph of Washington's Long Lake using water from that lake. The water's chemically polluted makeup caused the colorful distortions, transforming his picturesque photograph into an abstracted, painterly image.

Rollins Professor of Environmental Studies Dr. Lee Lines believes addressing climate crisis will require "a fundamental reimagining of nearly everything we do with fossil fuels." By capturing with immediacy the otherwise delayed visual impacts of environmental degradation, artists like Brandt may play an important role in provoking the necessary change for a reimagined social-environmental order.

Ria Brodell

(American, b. 1977)Butch Heroes: Cora Anderson aka Ralph Kerwineo 1876-1932, 2017

Gouache on paper

17 3/4 x 12 3/4 x 1 1/2 in. (45.09 x 32.39 x 3.81 cm)

Museum purchase from the Anniversary Acquisitions Fund. 2018.6. Image courtesy of the artist and Gallery Kayafas

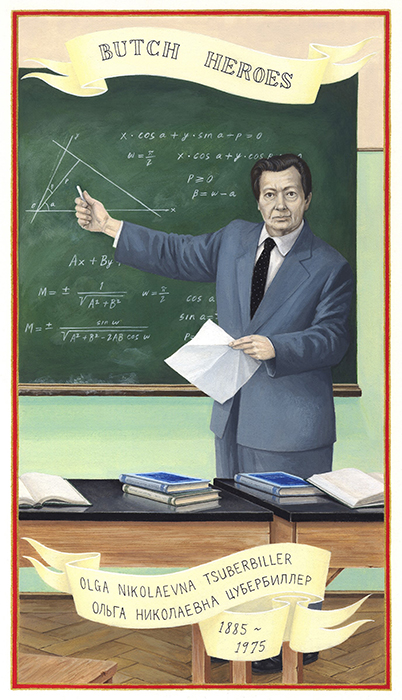

Ria Brodell

(American, b. 1977)Butch Heroes: Olga Nikolaevna Tsuberbiller 1885-1975 Russia, 2014

Gouache on paper

11 x 7 in.

Museum purchase with funds provided by the Diversity Council, Rollins College, 2018.5

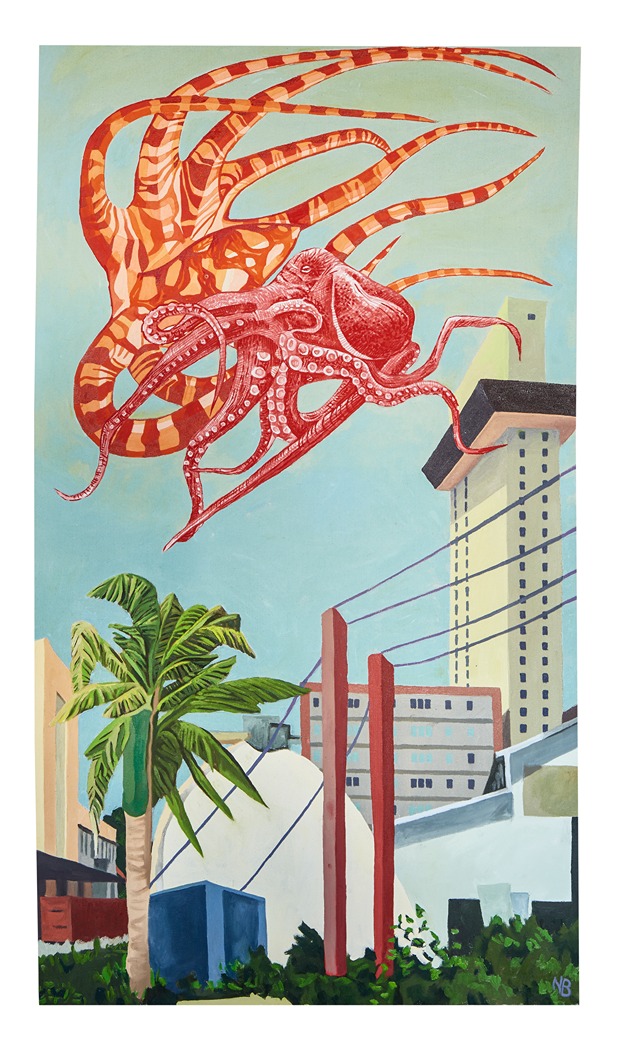

Nathan Budoff

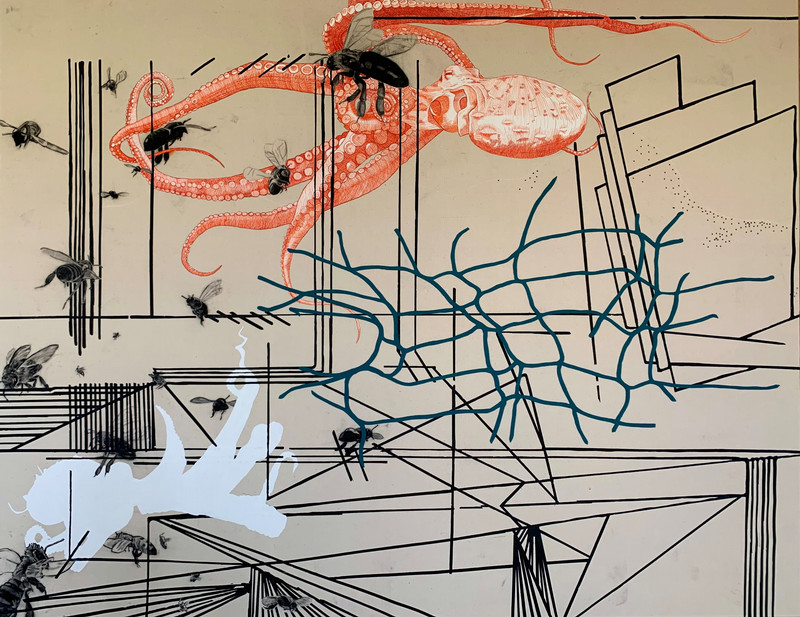

(American, b. 1962)Cosmic Love, 2017

Oil and shellac-base ink on canvas

Museum purchase from the Michel Roux Acquisition Fund, 2021.89 Image courtesy of the artist

Born in Brookline, Massachusetts, Nathan Budoff has lived in Puerto Rico for more than 25 years; the social and political context of the island as well as its environment have informed his practice. His recent body of work focuses on the Puerto Rican urban landscape and issues of dislocation and environmental deterioration.

In this painting, Budoff explores the contrasts between the urban and the natural environments. Against a light blue sky, an unrealistically large octopus and a squid hover over several iconic buildings in Santurce, Puerto Rico. The juxtaposition of impossible elements functions here as a metaphor for the imbalance in the man vs. nature relationship and its lasting impact. Budoff articulates a nuanced critique of the treatment of the environment in these tropical vistas; he invites us to imagine a world in which animals, however big or small in real life, take over our spaces: “I really wanted to bring forward the idea that other creatures live here with us, live all around us, and works like Cosmic Love are based on that conceit—what if our cities were really home to more than people and their dependents?”

Alexander Calder

(American, 1898-1976)Pyramids, 1970

Color Lithograph on Arches BSA

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert L. Gardner, 1983.33 © Alexander Calder/Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York, NY

Alexander Calder is one of the most highly regarded artists of the twentieth century, revered for his playful and whimsical adaptation of the forms and intellectual commitments of modernism. Trained as an engineer, Calder became interested in art, briefly studying at the Art Students League before decamping to Paris, where he became famous for his whimsical Cirque Calder (Whitney Museum of American Art), constructed out of wire, fabric, bits of cork, and other found objects. This led to his development of a series of wire sculptures, an early indication of his abiding interest in negative space. Shocked by a visit to the studio of Piet Mondrian into an embrace of abstraction, Calder would invent the motorized wire sculptures that fellow artist Marcel Duchamp would christen mobiles in 1931. Calder and his wife Louisa moved back to the United States in 1933, settling in Roxbury, Connecticut, where the wide open spaces of the surrounding countryside inspired him to work in ever-larger scales, further exploring the relationships between and among form, light, color, and space.

Calder rocketed to international superstardom after the end of World War II, and spent the following productive decades continuing to produce sculptures at all scales. He also worked prolifically in gouache, an opaque version of watercolor that allows the artist the quick freedom and re-wetting ability of watercolor while being easier to control. These gouaches—aggressively marketed in particular by his Paris dealer, Aimé Maeght—also proved exceptionally popular in the 1960s, particularly among middle-class consumers who could not necessarily afford or house one of his sculptures. Calder, whose commitment to the democratization of modernist abstraction and leftist politics have sometimes gone underremarked, seized on this opportunity, commissioning a number of lithographs based on the gouaches and aimed at an even more widespread audience. This is one such object, showing Calder’s mastery of the relationship between positive and negative spaces.

Alexander Calder

(American, 1898-1976)Swirl, ca. 1975

maguey fiber

Gift of Ms. Eva Shapiro, 1984.12.3 © Alexander Calder/Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York, NY

Calder’s interest in the democratization of modernism stemmed from his political commitments, which included a staunch antiwar orientation (he was an outspoken supporter of the Spanish Republic during the 1930s) as well as a lifelong interest in humanitarian causes. In 1972 an earthquake demolished the Nicaraguan capital city of Managua, killing and wounding thousands and leaving many more homeless. Calder was one of many international celebrities who contributed to relief efforts (another was Puerto Rican baseball star Roberto Clemente, who died in a plane crash on his way to the country). He commissioned Guatemalan artisans to create tapestries based on his gouaches out of maguey, an indigenous fiber made out of a species of agave plant. These he sold to help fund relief efforts.

The tapestries highlight another aspect of Calder’s career that is sometimes under-studied, which is his longstanding interest in a wide variety of practical and decorative arts. He frequently created functional objects—including pitchers, ashtrays, and other tableware—for his home, and fashioned rattles and other toys for his children. He also collaborated with Braniff International Airways to decorate several of their DC-8 aircraft, as well as jewelry and textiles. These broad interests have led some art historians to view him with suspicion, concerned that he was undermining the intellectual seriousness of his work (and modernism more broadly) with these works. Calder, long known as a jocular and playful man, was unconcerned, preferring to spread his work to as wide an audience as he could. That flexibility also extended to the materials in which the works were executed, as he accepted the imperfect translations necessitated by the traditional weaving process in this and other maguey fiber works.

Alexander Calder

(American, 1898-1976)Star, ca. 1975

maguey fiber

Gift of Ms. Eva Shapiro, 1984.12.8 © Alexander Calder/Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York, NY

Alexander Calder

(American, 1898-1976)Floating Circus, ca. 1975

maguey fiber

Gift of Ms. Eva Shapiro, 1984.12.10 © Alexander Calder/Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York, NY

Alexander Calder

(American, 1898-1976)Grand A Avec Moustaches, 1969

Color Lithograph on wove paper

21 3/4 x 29 5/8 in. (55.25 x 75.25 cm)

Purchased by the Wally Findlay Acquisitions Fund, 1990.10 © Alexander Calder/Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York, NY

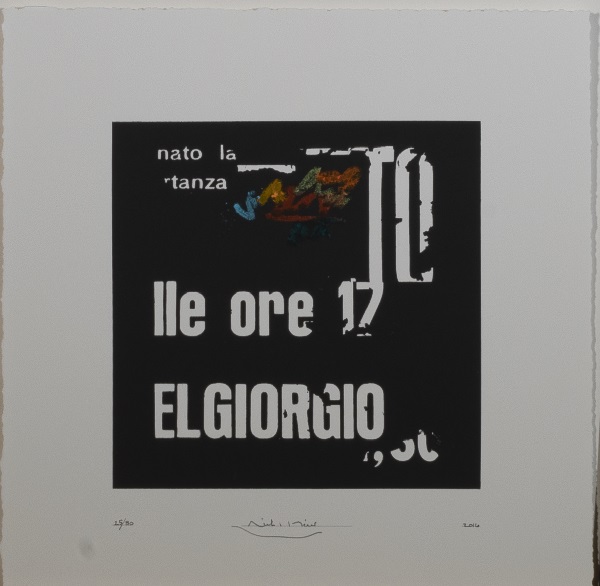

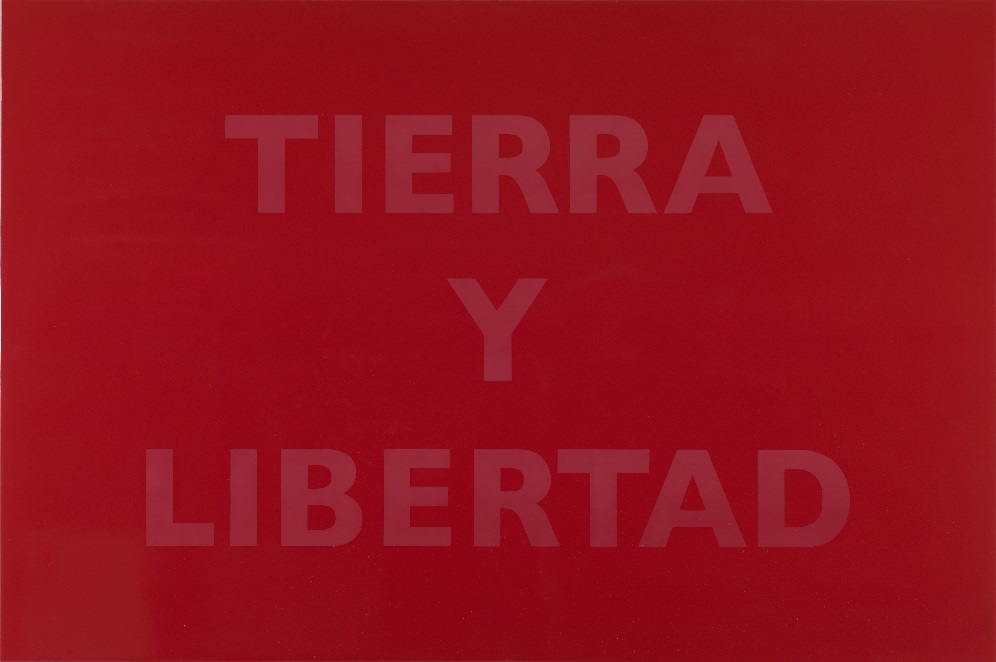

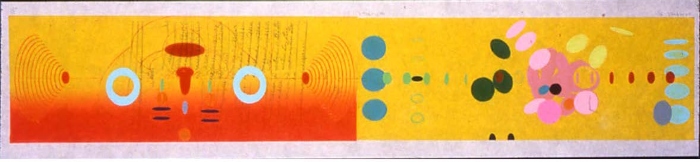

Luis Camnitzer

(Uruguayan, b. 1937)Timelanguage, 2016

Xerox toner on laid paper

48 x 114 in.

Museum purchase from the G.H. Smith Watch Key acquisitions Fund, 2017.8 © Luis Camnitzer (ARS), New York

Luis Camnitzer is a provocative thinker and artist. He makes work in myriad forms, choosing the format that he believes achieves his message or intent in the most direct manner. Like other conceptual artists, Camnitzer embraces the idea over the material manifestation of his creative practice.

Timelanguage derives from a body of work that includes rigorous consideration of the notion of time. The series of prints begins and ends with blank pages. The made up, composite term “timelanguage” unfolds across the successive prints, which evolve from a light gray to a final black image. Since the end and the beginning are a different color, but similar in composition, cyclical time as well as linear time become paramount here. Moreover, time is ephemeral and elusive. While modern society may feel governed by time, encapsulating the notion of time as a single entity remains a perplexing task.

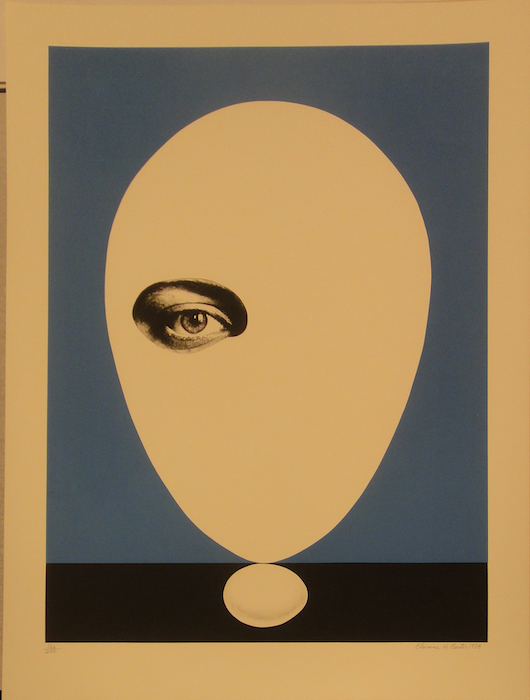

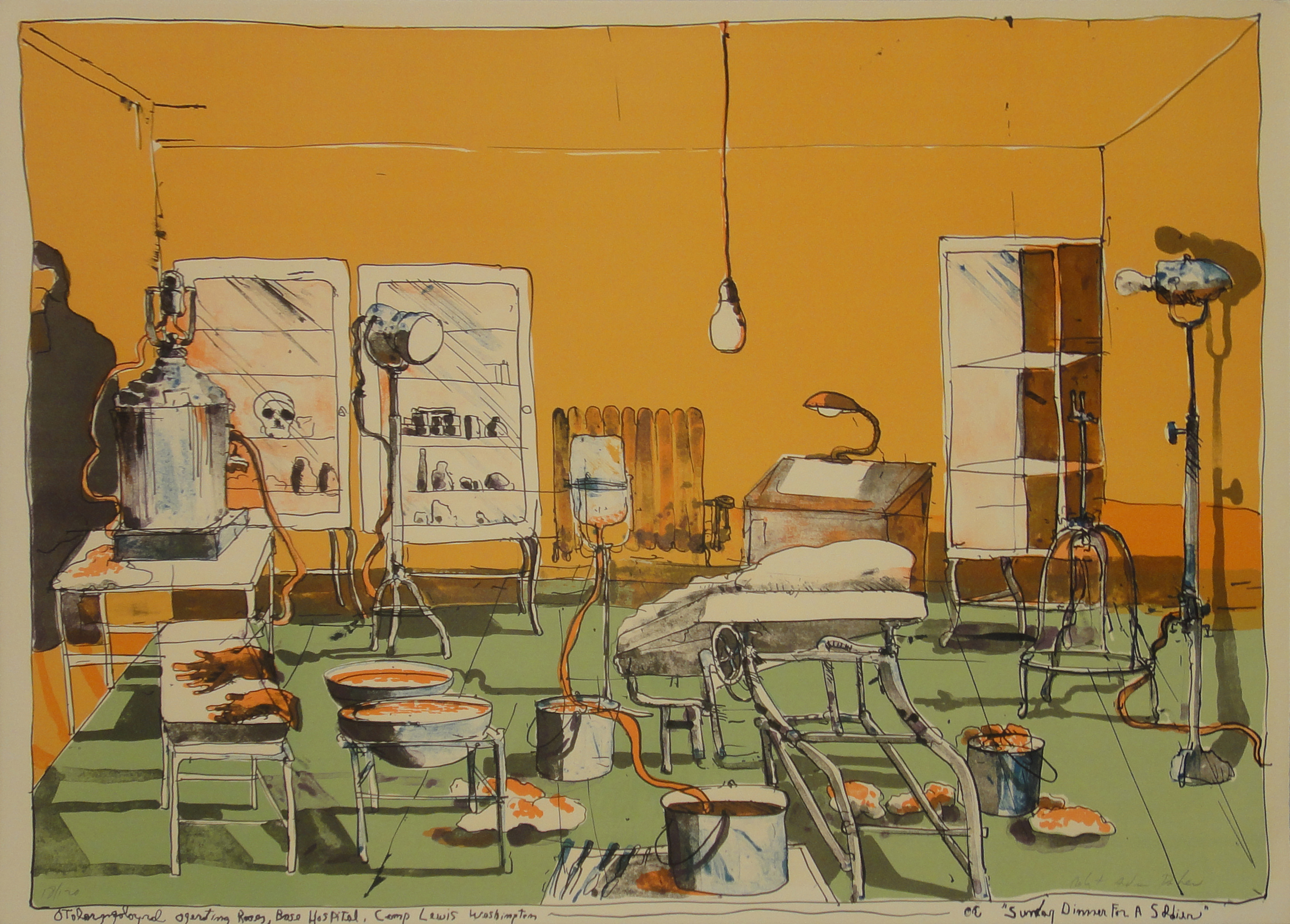

Clarence Holbrook Carter

(American, 1904-2000)Balancing Act, 1976

Serigraph

35 in. x 26 in. print

Gift of Paul O. Koether © Estate of Clarence Holbrook Carter, 2003.6.1

Clarence Holbrook Carter demonstrated facility with the difficult medium of watercolor early in his life, a talent which led him to study at the Cleveland School of Art before embarking for Italy to study with Hans Hofmann in 1927. Upon his return Carter taught, first in Cleveland and then in a variety of other cities including Pittsburgh, Minneapolis, and Atlanta. His early paintings were generally of the hard-edged realist style of American Scene painters like Edward Hopper. In the 1940s his work began to incorporate strange, incongruous elements, a shift that led to his inclusion in the Museum of Modern Art’s American Realists and Magic Realists exhibition in 1943. Later in his career—particularly after around 1970—he began to work in a Surrealist mode, creating empty, preternaturally still spaces populated only with one or more egglike, ovoid shapes.

These two silkscreens date from that era in his work. For Carter, the ovoid shapes came to stand in for a variety of contradictory elements of the human condition, such as life and death; mortality and immortality; the discrete self versus the expansive consciousness; and certainty versus mystery. Balancing Act, this work’s enigmatic title, alludes to the relationship between the two eggs, the larger of which seems to balance—or not—precariously on the edge of the other. The single eye disrupts the picture’s symmetry, staring out from the larger egg while also luring the viewer in and opening the possibility of an inner depth.

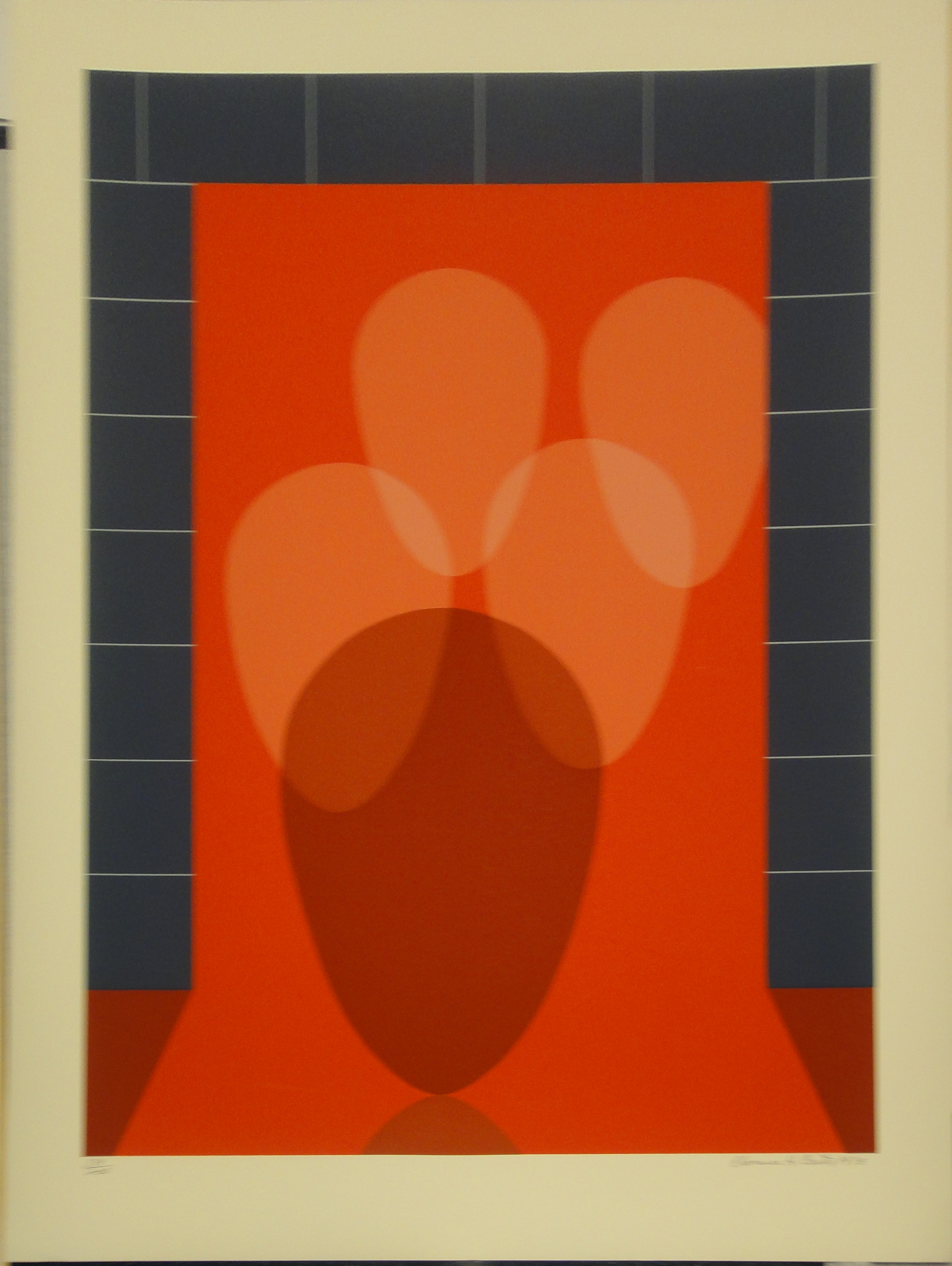

Clarence Holbrook Carter

(American, 1904-2000)Fiery Furnace, 1978

Serigraph

35 in. x 26 in. print

Gift of Paul O. Koether © Estate of Clarence Holbrook Carter, 2003.6.2

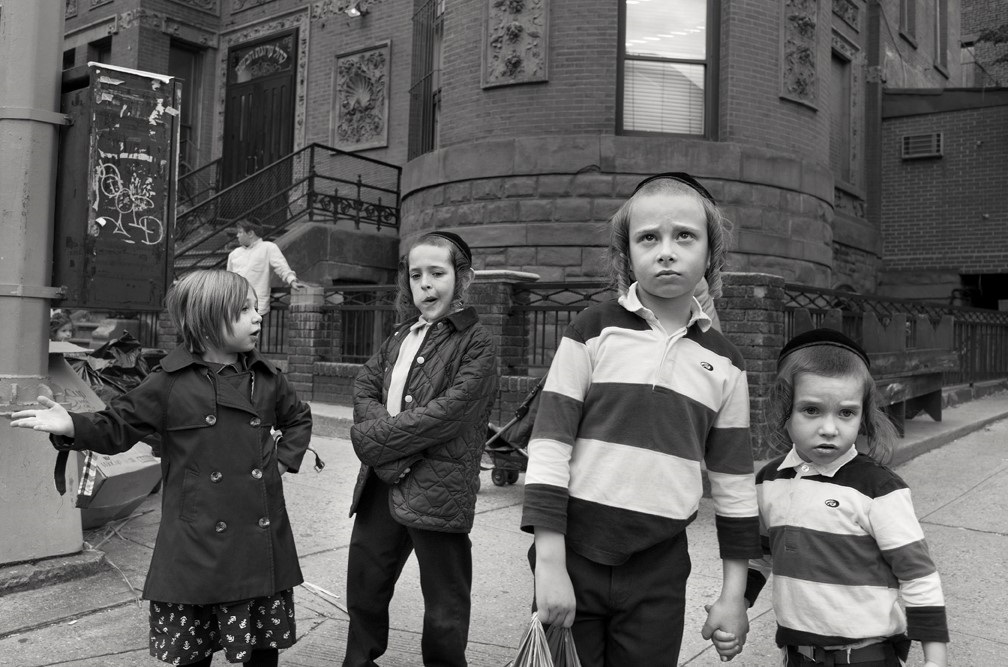

William Castellana

(American, b. 1968)Boys holding Hands/Bedford Avenue, Williamsburg, Brooklyn, 2017

Archival pigment ink print

13 x 19 in.

Gift of the Artist, 2017.19.1 © William Castellana

Born in Italy and working in New York City, William Castellana is both a commercial and fine-art photographer. He primarily works in still-life, a practice which has helped him to develop a keen eye for composition and lighting. These photographs, part of a series called South Williamsburg, represent something of a departure for Castellana, who took to the street to document his Brooklyn neighborhood. South Williamsburg is renowned for its high concentration of observant Jews, in particular the Hasidic group known as the Satmars. South Williamsburg also is home to a large secular population, with the two groups generally sticking to opposite sides of the appropriately named Division Avenue. In making the series Castellana was inspired by Henri Cartier-Bresson and other street photographers, forfeiting his usual careful control for a freer and more spontaneous approach.

He captured his images in black-and-white using a digital camera. The seeming paradox of using a modern technology to make old-looking images is a nod to the way in which the Orthodox residents of South Williamsburg undoubtedly live in the modern world while also holding beliefs and traditions apart from it. Residents of the neighborhood speak on cell phones, follow the directions of streetlights, and otherwise exist in contemporary Brooklyn. At the same time, they sport haircuts and garb that points to their status as deliberate outsiders. Castellana himself is an outsider in this milieu, and as such he is limited to the public aspects of Hasidic culture in Brooklyn. This distance limits his view but also perhaps sharpens it, allowing him to focus on the most visually striking images without an insider’s cultural baggage.

William Castellana

(American, b. 1968)Boys sitting on Stairs/Lee Avenue, Brooklyn, NY, , 2013

Archival pigment ink print

13 x 19 in.

Gift of the Artist. 2020.30 © William Castellana

William Castellana

(American, b. 1968)Boys with Milk Crates/Wallabout Street, Williamsburg, Brooklyn, 2017

Archival pigment ink print

13 x 19 in.

Gift of the Artist, 2017.19.2 © William Castellana

William Castellana

(American, b. 1968)Kids on Street Corner/Lee Avenue, Brooklyn, NY, 2013

Archival pigment ink print

13 x 19 in.

Gift of the Artist. 2020.32 © William Castellana

William Castellana

(American, b. 1968)Kids sitting on Milk Crates/Lee Avenue, Brooklyn, NY, 2013

Archival pigment ink print

13 x 19 in.

Gift of the Artist. 2020.28 © William Castellana

William Castellana

(American, b. 1968)Three Boys Running/Lee Avenue, Brooklyn, NY, 2013

Archival pigment ink print

13 x 19 in.

Gift of the Artist. 2020.31 © William Castellana

William Castellana

(American, b. 1968)Untitled/Wilson Street, Williamsburg, Brooklyn, 2017

Archival pigment ink print

13 x 19 in.

Gift of the Artist, 2017.19.3 © William Castellana

William Castellana

(American, b. 1968)Women picking Food Container/Penn Street, Brooklyn, NY, 2013

Archival pigment ink print

13 x 19 in.

Gift of the Artist. 2020.29 © William Castellana

Elizabeth Catlett

(American, 1915 - 2012)Naima, 2009

Patinated bronze

11 1/2 x 9 1/2 x 5 1/2 in

Museum purchase from the Michel Roux Acquisition Fund, 2017.07 © Elizabeth Catlett/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Elizabeth Catlett was known for sculptures that reflected both African American and Mexican identities. Catlett’s influences include the works of the Harlem and Chicago Renaissances, as well as modern and African art. Naima exemplifies the artist’s balance between the figurative and the abstract, potentially stemming from the influence of her mentor, modernist sculptor Ossip Zadkine (1888–1967). Catlett challenged Zadkine’s abstraction with her background in African art, blending her knowledge of the two to convey the essence of the subject without extraneous detail, but also without losing accessibility, as she created art to be consumed by everyday African American people. In keeping with this, she rejected the idea of the modernist “international figure,” instead creating a form that elicits sympathy from her viewers. Naima was inspired by her own granddaughter, Naima Mora, after she visited Catlett’s home in Mexico to study Spanish. Naima’s elongated profile fits within Catlett’s existing work, which draws from the cultural significance of the head in African art. In Yoruba figure sculpture, the head is the most vital part of a person. It is regarded as the epicenter of one’s individuality, sensory experience, nourishment, and wisdom. Just as Catlett wishes to portray the essence of her granddaughter, the head portrays the essence of human personality and the source of life in Yoruban culture, not only in the present, but also for the future.

Nick Cave

(American, b. 1959)Drive-By, 2011

Blue-ray Disc

16 minutes

Gift of Nilani Trent. 2019.12 © Nick Cave

Nick Cave’s work is characterized by community participation and celebration. Born in Fulton, Missouri, the artist creates pieces in which sculpture, performance, and dance converge. His “soundsuits” consist of elaborate costumes that cover the entire body concealing the wearer’s identity, gender, race, and age. The suits incorporate sequins, raffia, fabric, buttons, and other common materials, evoking diverse traditions and cultural practices. Together with dancers, choreographers, and community members, Cave orchestrates performances in public spaces where passersby are encouraged to join in and participate. The artist created the first soundsuit in 1992 in response to the beating of Rodney King, an African American man, by California police officers. This incident of police brutality led Cave to reflect on his own identity as a Black man and the vulnerability that presents in contemporary society. In this piece the suits are activated by movement and sound, creating a powerful visual that celebrates freedom and community. In the artist’s own words: “I felt like my identity and who I was as a human being was up for question. I felt like that could have been me. Once that incident occurred, I was existing very differently in the world. So many things were going through my head: How do I exist in a place that sees me as a threat?”

Read the Virtual Lavender Label for this work.

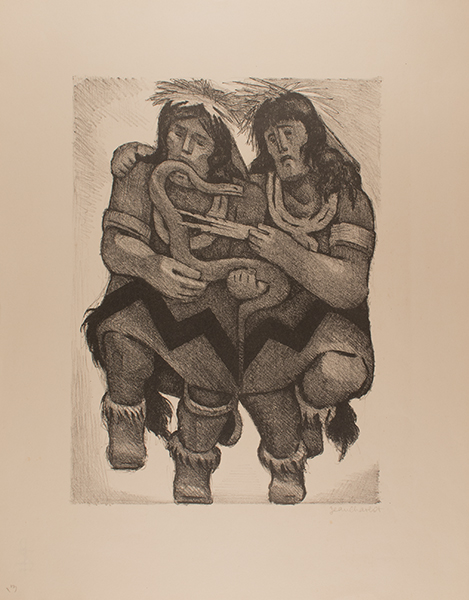

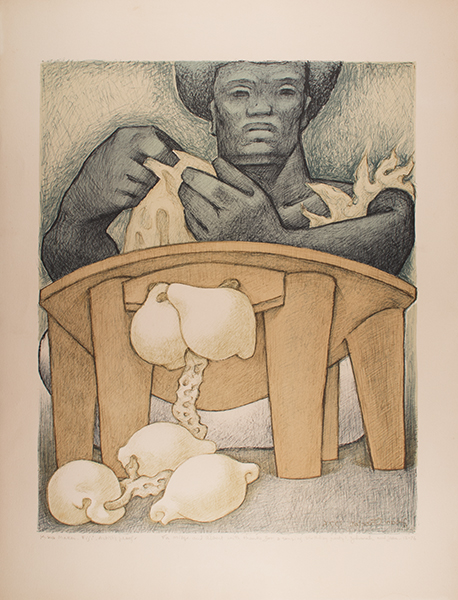

Jean Charlot

(American, b. Paris, France, 1898-1979)Hopi Snake Dance, 1952

Lithograph

19 x 15 in.

Gift of Charles and Julie Day Pinney, 2017.11.4 © Jean Charlot/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Hopi snake dance is a sacred ritual performed for centuries by Hopi men every August after days of preparation. It is a way to give thanks and to ask the spirits for good fortune. Created by French artist Jean Charlot, this image depicts a moment in the ritual when a dancer holds a snake in his mouth while the figure on the right calms the animal with a feather stick. In the 1940s and early ‘50s, the Hopi Reservation in Northeastern Arizona became a destination for travelers who were curious about the ritual, among them President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Eventually, the celebration of the ritual was closed to the public.

Charlot was born in France and moved to Mexico with his mother after his father’s passing in 1921. There, in the context of his maternal ancestors, the young artist flourished, playing a key role in the Mexican muralist movement of the 1920s. Eventually he moved to the U.S. where he worked as an educator, artist, and writer. This work is part of a series that depicts the Hopi Snake Dance mural Charlot created at Arizona State University where he taught summer courses. In 1949 the artist moved to Hawaii where he taught at the University of Hawaii at Manoa for almost two decades.

Jean Charlot

(American, b. Paris, France, 1898-1979)Hopi Snake Dance, 1956

16 3/8 x 12 1/2 in.

Gift of Charles and Julie Day Pinney, 2017.11.6 © Jean Charlot/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

This print was a result of the trip Charlot took to Tempe, Arizona to execute a mural at Arizona State University. As he did with his study of Mexican and Hawai’ian culture, Charlot rigorously prepared, reading an 1884 book—illustrated with chromolithographs—called The Snake Dance of the Moquis of Arizona by J. G. Bourke. While he was in Arizona he saw a group of Hopi perform the dance, executing the print with master lithographer Lynton Kistler in Los Angeles on his way back to Hawai’i. Charlot had hoped to sell copies of this print to Arizona State students for $5, but few were interested. As a result, Kistler estimates that only about 35 of the intended edition of 250 were ever printed.

Jean Charlot

(American, b. Paris, France, 1898-1979)Mock Battle, 1956

Color lithograph

21 1/2 x 14 3/8 in.

Gift of Charles and Julie Day Pinney, 2017.11.7 © Jean Charlot/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jean Charlot

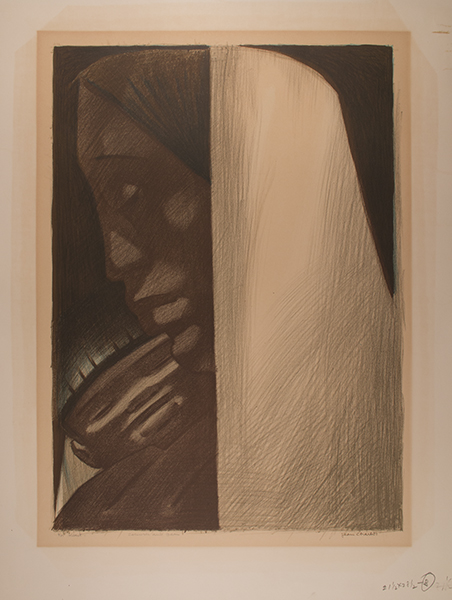

(American, b. Paris, France, 1898-1979)The Dark Madonna, 1954

Lithograph

24 7/8 x 19 1/4 in.

Gift of Charles and Julie Day Pinney, 2017.11.8 © Jean Charlot/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Influenced by the indigenous art and culture of Mexico, Jean Charlot represents in this image a tender moment between mother and child. Departing from the conventions of Western depictions of the Virgin Mary and the infant Jesus, Charlot reimagines the religious figures as a dark-skinned woman and small child. The composition is divided into two vertical registers creating a stark contrast between light and dark. On the left, the Madonna is depicted in profile while holding her son, both with eyes closed in an intimate scene that conveys warmth and care. The light veil over her head occupies most of the right side of the image leaving no room for background or contextual elements inviting viewers to focus on the faces of the figures and what they represent.

Charlot lived in Mexico during the 1920s where he worked as an artist and educator. He had an important role in Mexican modernism and in the muralist movement, first as an assistant to Diego Rivera and eventually as a muralist painter himself receiving numerous commissions for public buildings. Charlot created this image while working as an art professor at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. The impact of Mexican art and folklore on the artist’s stylistic and thematic choices is evident throughout his career.

Jean Charlot

(American, b. Paris, France, 1898-1979)Mock Victory, 1956

Color lithograph

21 1/4 x 14 1/2 in.

Gift of Charles and Julie Day Pinney, 2017.11.9 © Jean Charlot/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jean Charlot

(American, b. Paris, France, 1898-1979)Little Seamstress, 1974

Linocut and woodcut

6 1/4 x 8 5/8 in.

Gift of Charles and Julie Day Pinney, 2017.11.12 © Jean Charlot/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jean Charlot

(American, b. Paris, France, 1898-1979)Tagane daura vuravu/Ancient warrior, 1976

Lithograph

26 x 19 3/4 in.

Gift of Charles and Julie Day Pinney, 2017.11.15 © Jean Charlot/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jean Charlot

(American, b. Paris, France, 1898-1979)Sorcerer in Hala Grove, 1974

Lithograph

25 3/4 x 20 in.

Gift of Charles and Julie Day Pinney, 2017.11.16 © Jean Charlot/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jean Charlot

(American, b. Paris, France, 1898-1979)Spear Thrower, 1974

Silkscreen

20 x 25 3/4 in.

Gift of Charles and Julie Day Pinney, 2017.11.18 © Jean Charlot/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jean Charlot

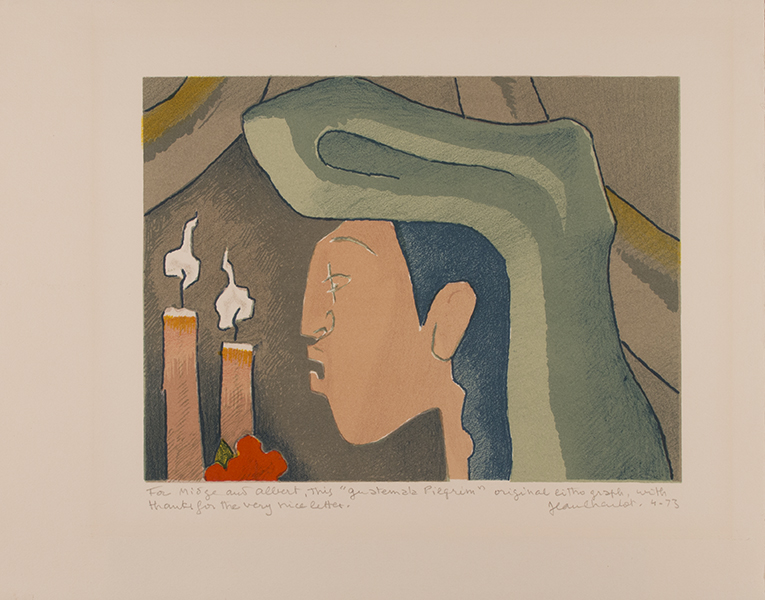

(American, b. Paris, France, 1898-1979)Guatemala Pilgrim, 1973

Lithograph

9 x 11 1/2 in.

Gift of Charles and Julie Day Pinney, 2017.11.20 © Jean Charlot/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jean Charlot

(American, b. Paris, France, 1898-1979)Kava Ceremony, 1976

Lithograph

25 3/4 x 20 in.

Gift of Charles and Julie Day Pinney, 2017.11.21 © Jean Charlot/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jean Charlot

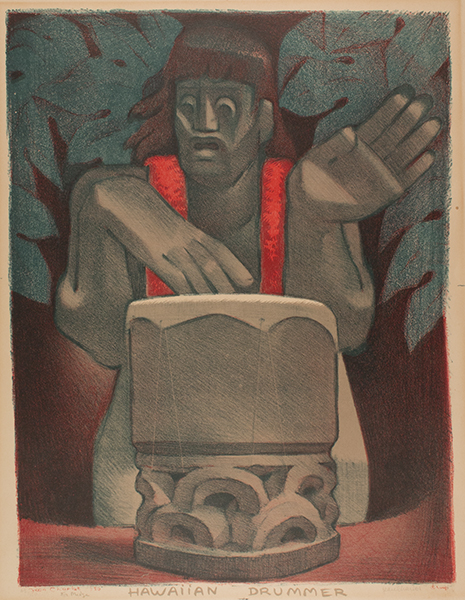

(American, b. Paris, France, 1898-1979)Hawaiian Drummer, 1950

Color lithograph

18 x 14 in. (45.72 x 35.56 cm) print

Gift of Charles and Julie Day Pinney, 2017.11.22 © Jean Charlot/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Zoya Cherkassky

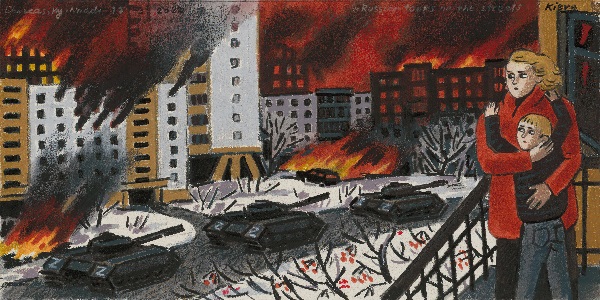

(Israeli, b. 1976)Russian tanks on the streets of Kiev, 2022

Archival inkjet print

11 x 17 in.

Museum purchase from the Michel Roux Acquisition Fund, 2022.6 © Zoya Cherkassky. Courtesy of the artist and Fort Gansevoort

Born and raised in the Soviet Union, Zoya Cherkassky moved to Israel when she was fifteen years old. Memories of her youth and of the landscape in which she grew up often inform her artistic practice. In this work, Cherkassky creates a strong visual statement denouncing the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. A weary mother and small child hold each other tight as they witness Russian tanks rolling through the city of Kiev as the buildings in the background go up in flames. The scene captures the immediate threat to life and the destruction of the Ukrainian capital. In a public statement published shortly after the invasion began, Cherkassky reflected, “Most of the images from my project 'Soviet Childhood' are based on Kiev landscapes. Today I see all of them being bombed and burned by the Russians.” The artist created a limited edition of this print as a fundraiser for Ukraine relief, donating parts of the proceeds to the International Committee of the Red Cross to help mothers and families keep their children safe.

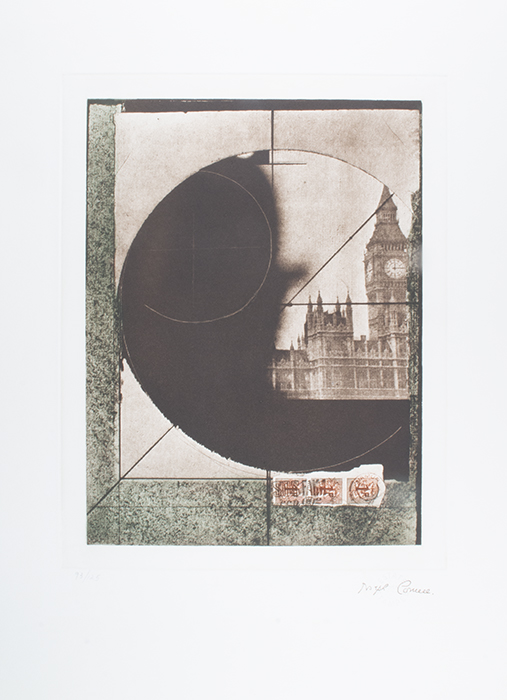

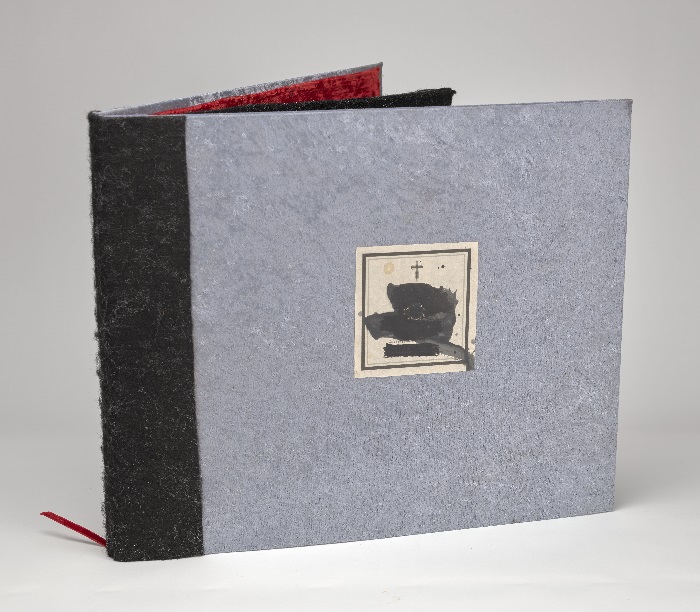

Joseph Cornell

(American, 1903-1972)Untitled (Derby Hat), 1972

Heliogravure

13 ¼ in x 10 ¼ in. Print

Purchased by the Wally Findlay Acquisitions Fund. 1993.3 © The Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

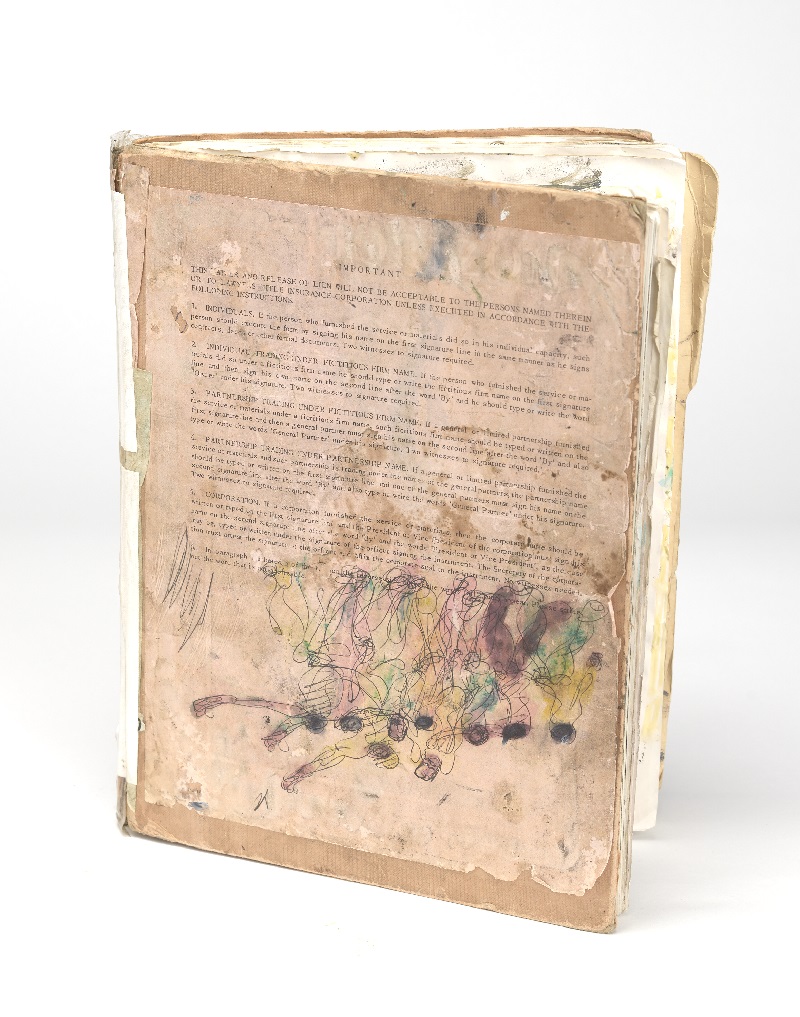

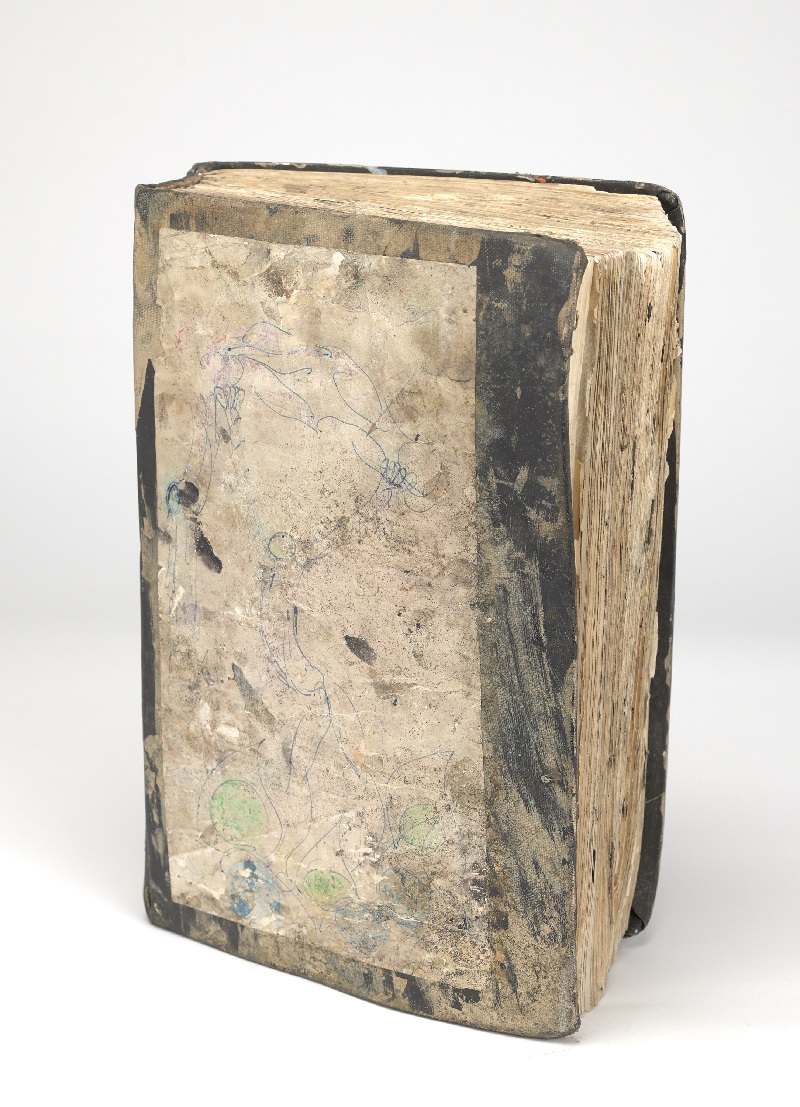

One of the twentieth century’s most singular artists, Joseph Cornell developed a highly personal aesthetic and metaphysical vocabulary that was informed by his travels around New York City, his Christian Science faith, his encounters with Surrealism and other avant-garde art, and his interest in nature, time, astronomy, and a number of other subjects. A careful and at times obsessive collector, Cornell spent his entire life gathering materials in New York’s junk shops, categorizing them by subject matter in the voluminous files he kept in his Queens home. Over the course of his long and productive career Cornell produced dozens of collages and assemblages—the latter of which are frequently known as Cornell Boxes—out of these files, as well as several films.

This work, dating from near the end of his life, was created to benefit the charity Phoenix House, a nationwide drug treatment and prevention organization that primarily focused on treating children, adolescents, and families. Cornell—a lifelong lover of children—was moved to help the organization after he met a pair of teenaged addicts. Heliography is an early form of photographic printing, and its use reflects Cornell’s interest in Victorian motifs and technologies. The print’s combination of circles reflects his interest in both astronomy and time, the latter of which is also conjured by the reproduction of the iconic Big Ben. The title, Untitled (Derby Hat) is not clearly referenced anywhere in the print, contributing to its haunting, dreamlike qualities, which are further emphasized by the almost haphazard way in which the various elements seem to be joined together.

Earl Cunningham

(American, 1893–1977)Canal with Water Hyacinth, ca. 1960

Oil on masonite

16 x 20 in.

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Yochum 2015.24

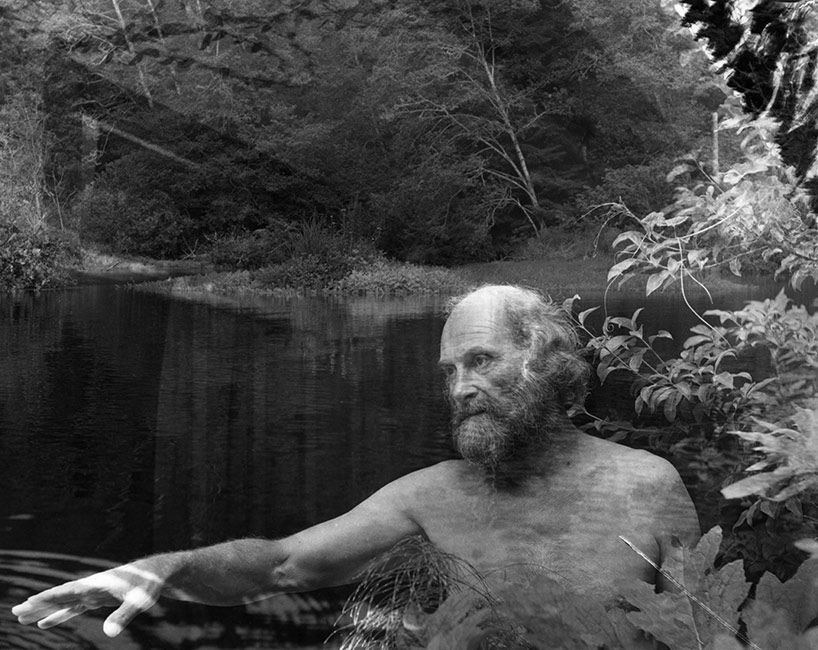

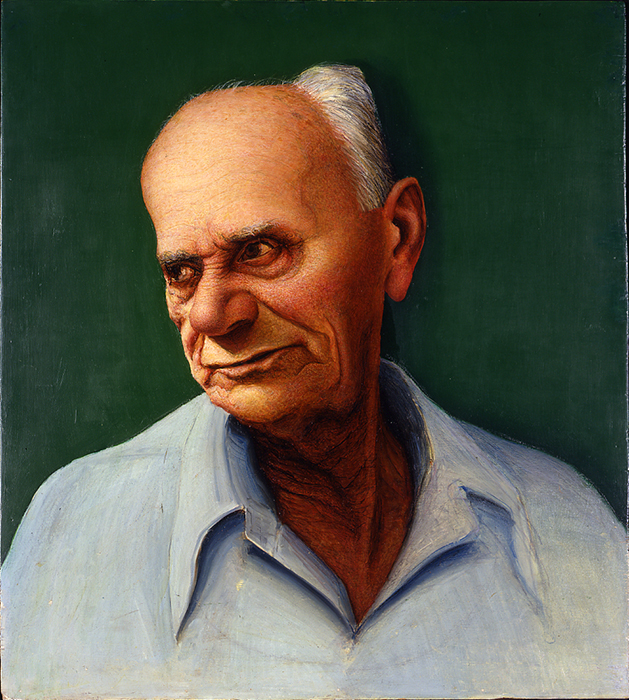

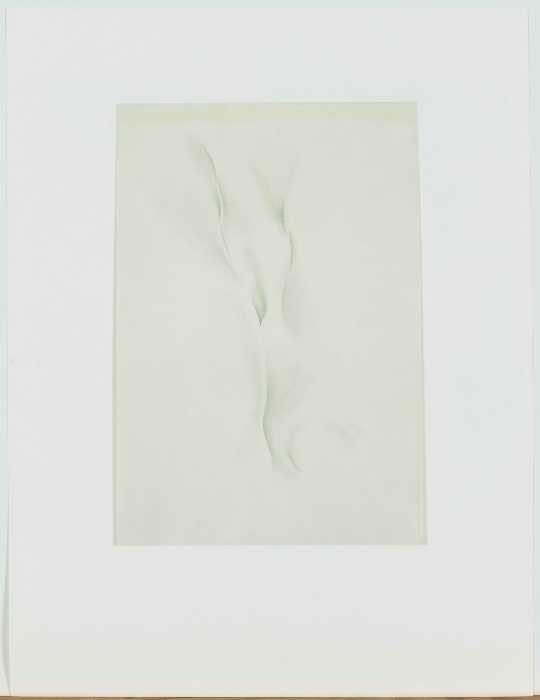

Imogen Cunningham

(American, 1883–1976)Pentimento, 1973

Photographic print

17 1/4 x 14 1/4 in.

Purchased with the Michel Roux Acquisitions Fund, 2013.14

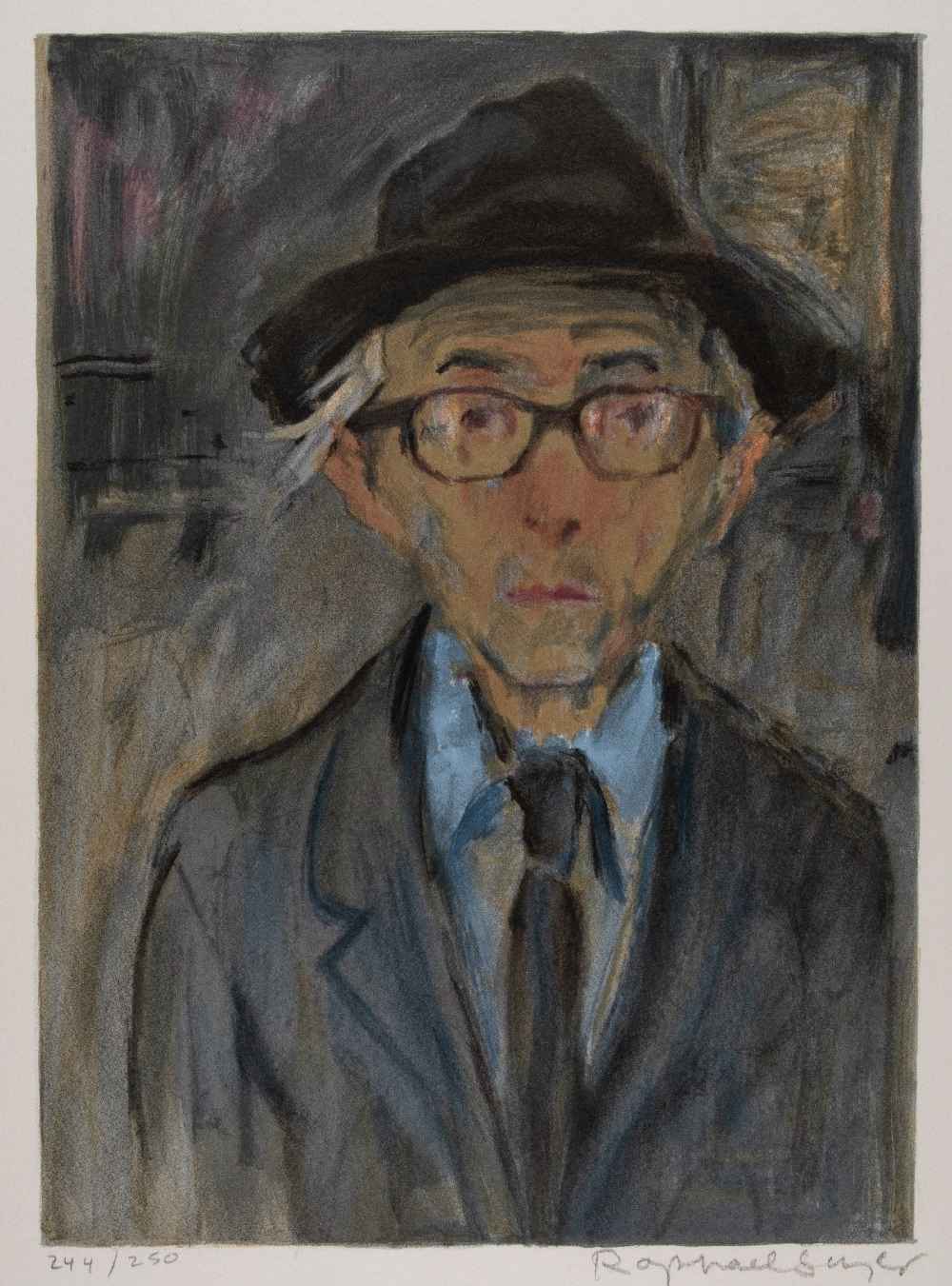

The first time Imogen Cunningham photographed the transcendental painter Morris Graves was in 1950 on the grounds of his private retreat outside Seattle. An introspective portrait study of Graves who as a conscientious-objector had refused to enter the military during World War II resulted in his imprisonment, Cunningham’s photograph is considered a classic portrait. The photographer commented about the image, “Many people think it’s the only portrait I’ve made. You know, he’s never said whether he like it or not.”

Nearly twenty years later, in 1969, Cunningham sought out the reclusive Graves to include him in her venture After Ninety, a project about old age. He turned her down. She was persistent and several years later, in 1973, he agreed to have her photograph him, musing, “How can anyone refuse a 90-year old like Imogen anything?” Cunningham was 90 and Graves 63.

As a college student, Imogen studied chemistry and worked in the botany department of the University of Washington. She became interested in photography in 1905 working with a 4 x 5 camera ordered through a mail-order correspondence school. Gertrude Käsebier’s 1907 article published in The Craftsman inspired her. Cunningham worked in the Seattle studio of Edward S. Curtis, a chronicler of Amerindians, for two years beginning in 1907, learning the fine points of platinum printing and retouching of negatives. Following a fellowship to Dresden, Germany where she studied with a photo chemist, viewed the International Photographic Exhibition and artwork at museums, she opened a portrait studio in 1910 upon her return to Seattle.

Throughout her career that spanned 70 years Cunningham featured portraiture and images of the body including nudes, however she is most well known for the photographs emanating from her affiliation with the California formalists group F/64 that included photographers Edward Weston and Ansel Adams. The name derived from the f-stop on the camera that provided the sharpest focus and depth of field. Inspired by these associations Cunningham developed her early style—close-ups photographs of industrial complexes, botanical plants and flowers—calla lilies and magnolias blossoms. Ten of these photographic studies debuted in the exhibition Film und Foto featuring works by American and European artists held in Stuttgart, Germany in 1929.

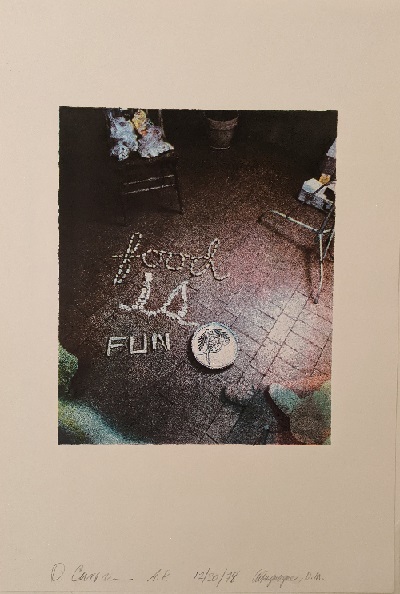

Darryl Curran

(American, b. 1935)Food is Fun, 1978

CMYK screen print from camera

20 x 15 in.

Gift of the artist and The Museum Project. 2022.7. © Darryl Curran

Darryl Curran

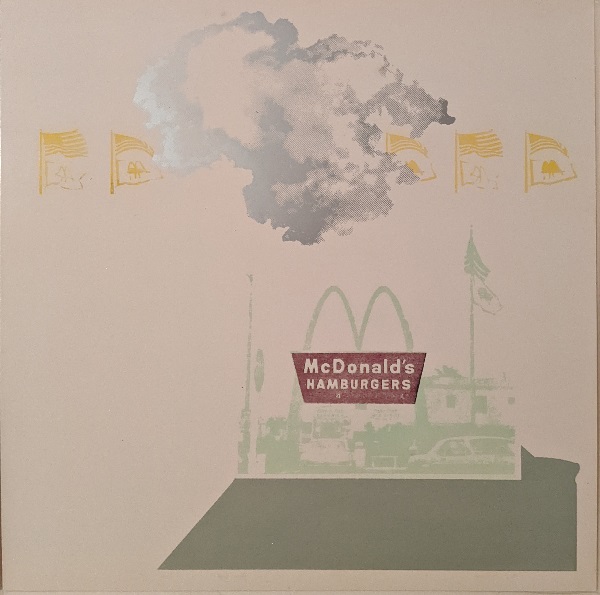

(American, b. 1935)Nutrition Program (Clouds, Fast Food), 1971

Photo silkscreen

15 x 15 in.

Gift of the artist and The Museum Project, 2022.8 © Darryl Curran

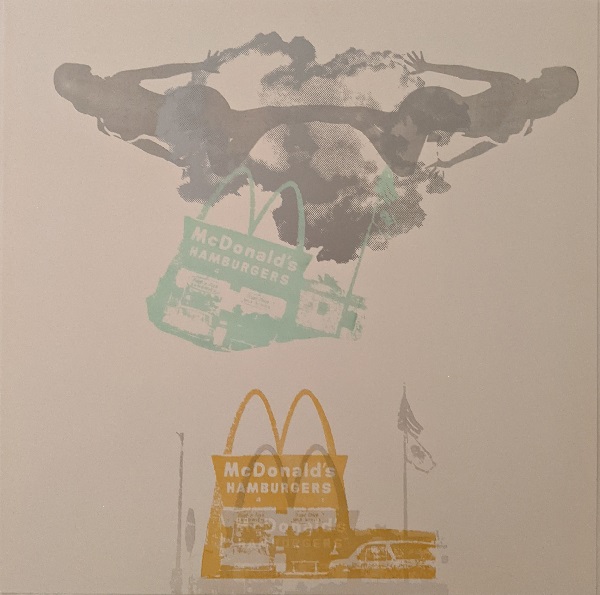

Darryl Curran

(American, b. 1935)Nutrition Program (Figures, Clouds), 1972

Photo silkscreen

15 x 15 in.

Gift of the artist and The Museum Project, 2022.9 © Darryl Curran

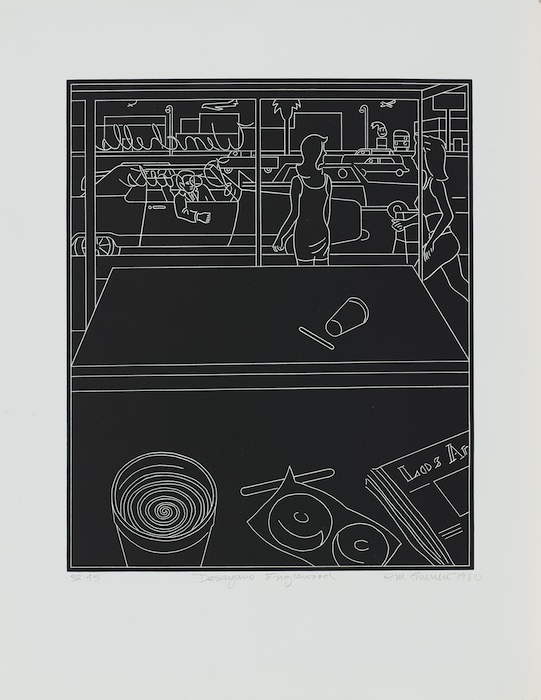

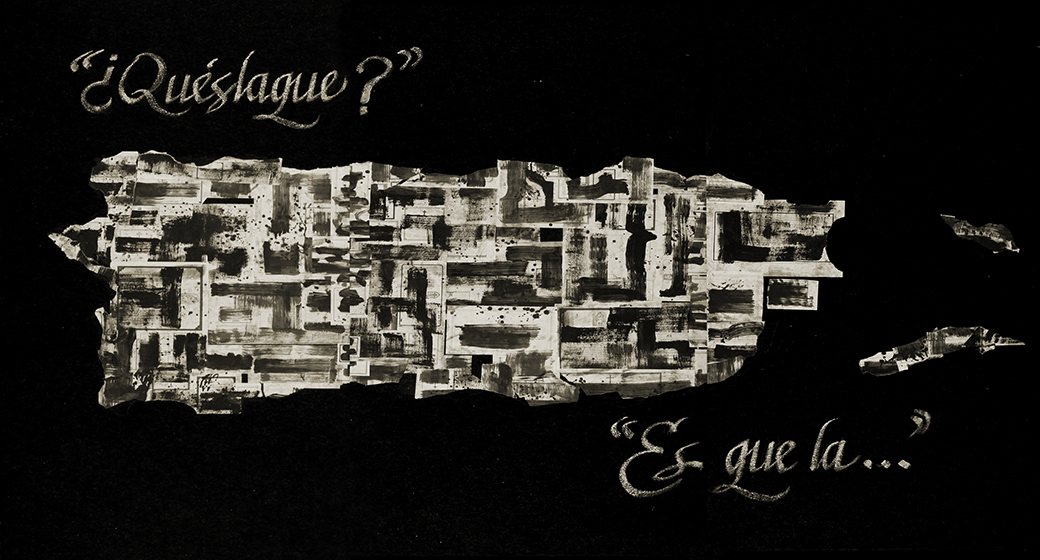

Carlos Dávila Rinaldi

(Puerto Rican, b. 1958)Departure, 2009

Acrylic on canvas

72 x 48 in.

Gift of Anonymous ’86. 2020.34 © Carlos Dávila Rinaldi

For Carlos Dávila Rinaldi, airports are rich environments that stimulate his creativity: “People in a hurry, others lost looking for their gate or just learning of a delay, the all familiar airport scene where some of us begin to taste the rush of traveling to a familiar place or perhaps somewhere you’ve never been. Airports are my kind of habitat...sensory overload at its fullest.”

Bold, gestural markings across the surface of this work suggest the sights, sounds, and movement of passengers through a terminal. Thick, black lines, patches of bright yellow, and red evoke the fast-paced nature of this environment. Like catching a glimpse of a suitcase rolling by or the colorful pattern of a passenger’s clothing, each area of the painting conveys the intense and chaotic experience of the airport. In smaller light blue, lavender, white and gray sections of the work, the artist seems to capture details of objects around him, those perhaps perceived while glancing around the gate and taking it all in. Here, Dávila Rinaldi dissects his experience of travel and transforms it into an equally intense and fragmentary visual. His expressive abstract style is informed by tachism, a mid-twentieth century artistic style characterized by spontaneously applied patches of color and the emphasis on the artist’s feelings and individual experience.

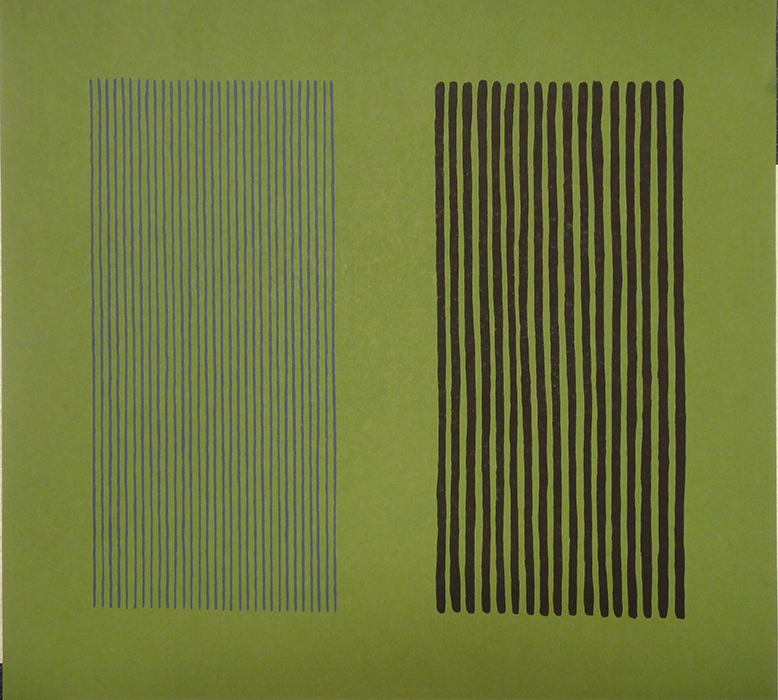

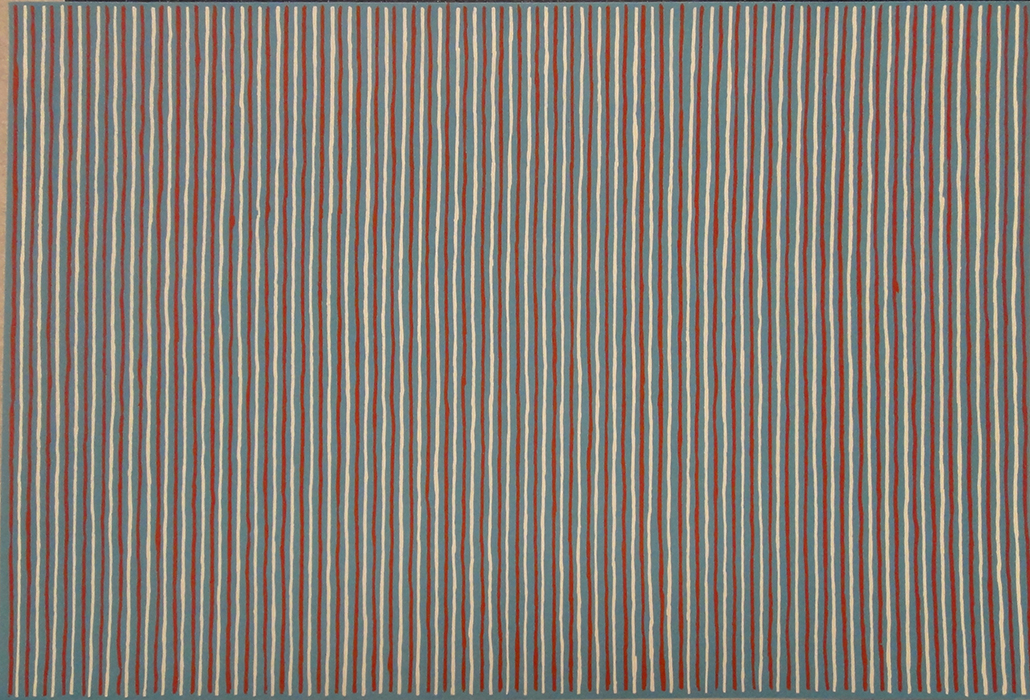

Gene Davis

(American, 1920 - 1985)Green Giant, lithograph

26 in. x 29 in. print

Mr. Eugene Ivan Schuster © Estate of Gene Davis/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, 1991.23.5

Gene Davis

(American, 1920 - 1985)Sonata, 1981

lithograph

20 5/8 in. x 28 1/2 in. print

Gift of Mr. Eugene Ivan Schuster © Estate of Gene Davis/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, 1991.23.6

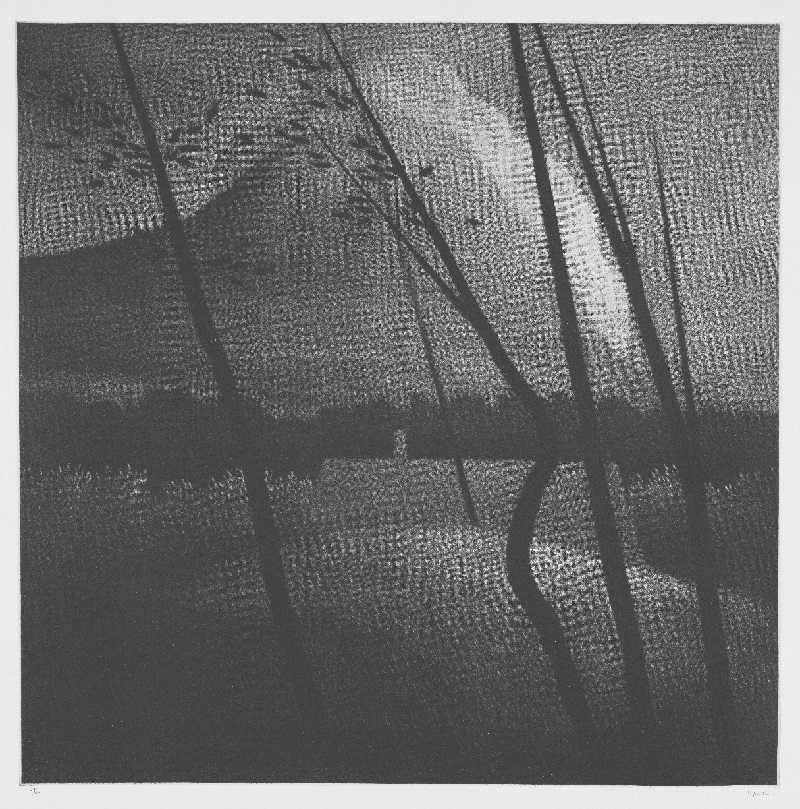

Gene Davis worked as a sports reporter and writing copy for the American Automobile Association before he decided to become a full-time painter. When he did, Abstract Expressionism was ascendant, and he joined the general trend for deeply personal, painterly abstractions. Like other members of what would become known as the Washington Color School, however, he soon began to tire of expressionism, instead beginning to evolve a cool, hard-edged style that embraced the line as its primary formal element. This shift brought him nearly instant recognition, as the influential critic Clement Greenberg included him in his landmark 1964 exhibition Post Painterly Abstraction. This success was followed by his inclusion in Washington Color Painters in 1965, alongside Kenneth Noland, Morris Louis, and other local abstractionists. Unlike these figures—Noland in particular—Davis always retained a less cerebral, more playful style, and he was a fixture as a teacher as well as in Washington cultural society.

Davis’s color sense was honed among Washington’s idiosyncratic Phillips Collection, where he gravitated in particular to the Impressionists as well as the work of Swiss modernist Paul Klee. He advised viewers to approach his works by singling out one of the colors, allowing their eye to travel from one instance of it to another. This sliding across the canvas—across what he termed its intervals—creates a sense of kaleidoscopic motion that is almost cinematic in its intensity. His invocation of the interval also points to his love of music, which he enjoyed for its analytic and mathematical precision as well as its expressive potential. Though he claimed to dislike romantic subject matter, preferring Steve Reich to Beethoven, for example, he also insisted upon the presence of a romantic component in his own work. The title of this work, Sonata, particularly reveals his musical bent. The irregular lines run vertically along the sheet, creating a shimmering visual counterpart to the repeated variations that form a musical composition.

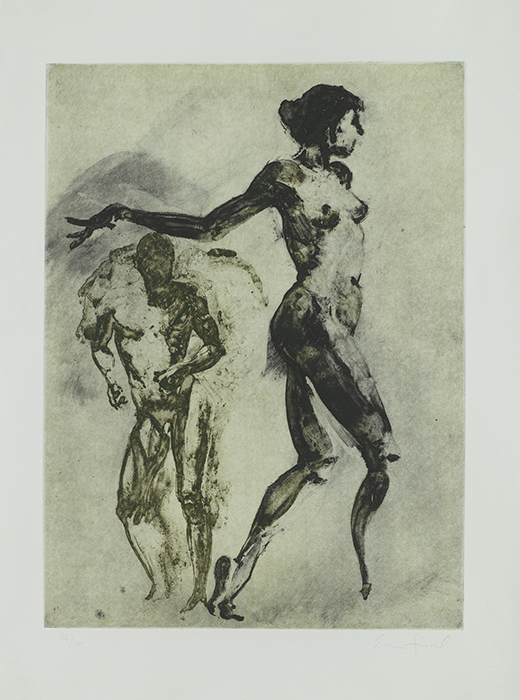

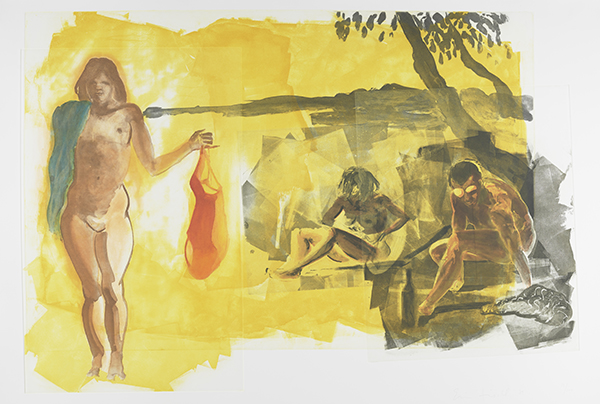

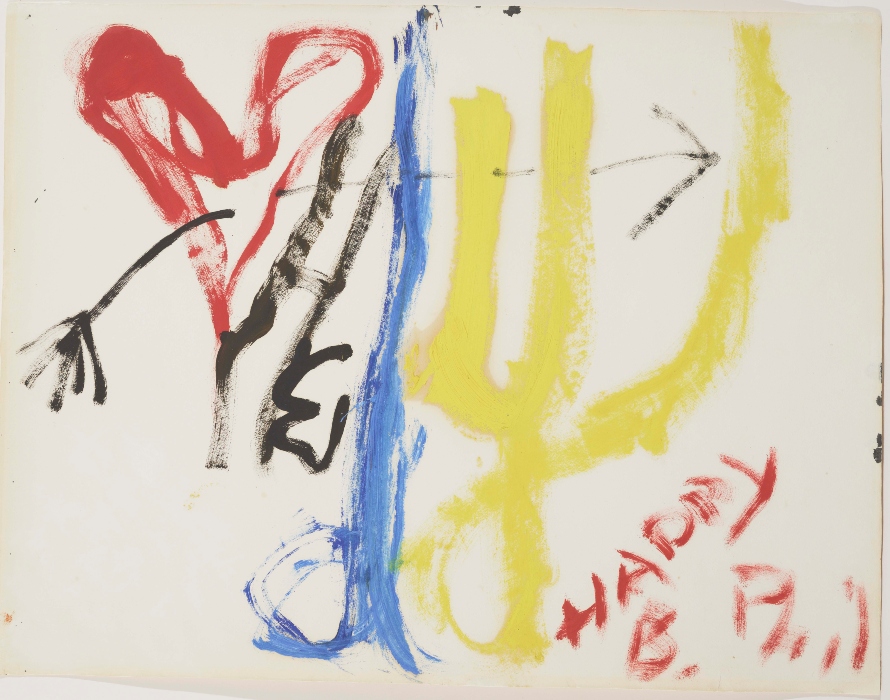

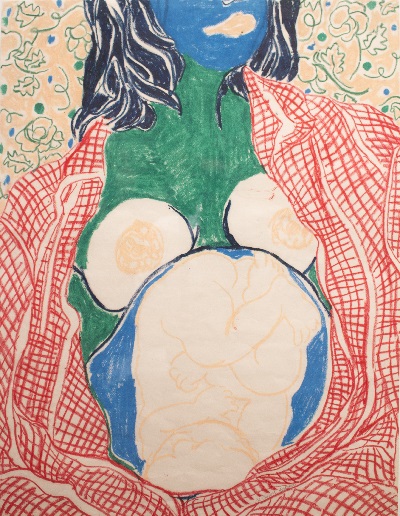

Willem de Kooning

(American, 1904-1997)Two Women, 1973

Lithograph on paper

18 x 15 in.

Museum Purchase from the Wally Findlay Acquisition Fund, 1997.13

Willem de Kooning, one of America’s most influential twentieth century artists, was a first-generation Abstract Expressionist. Abstract Expressionism radically changed the way in which people thought about art, as artists began creating spontaneous, expressive, and emotional works. Improvisation in the artistic process produced a dynamism and energy seen in the use of gestural brushstrokes and bright, acidic colors. While his contemporaries moved away from representational imagery, de Kooning favored figural abstraction. The female nude was a recurring subject matter for the artist, and this work is emblematic of De Kooning’s artistic practice. He gained recognition in the artworld for his “Women” series created from 1950-1953, which comprised of six oil paintings titled Woman I through Woman VI. In his later work, Two Women, de Kooning depicts the female form with dynamic, expressive linework that emphasizes the movement and physicality of the figures.

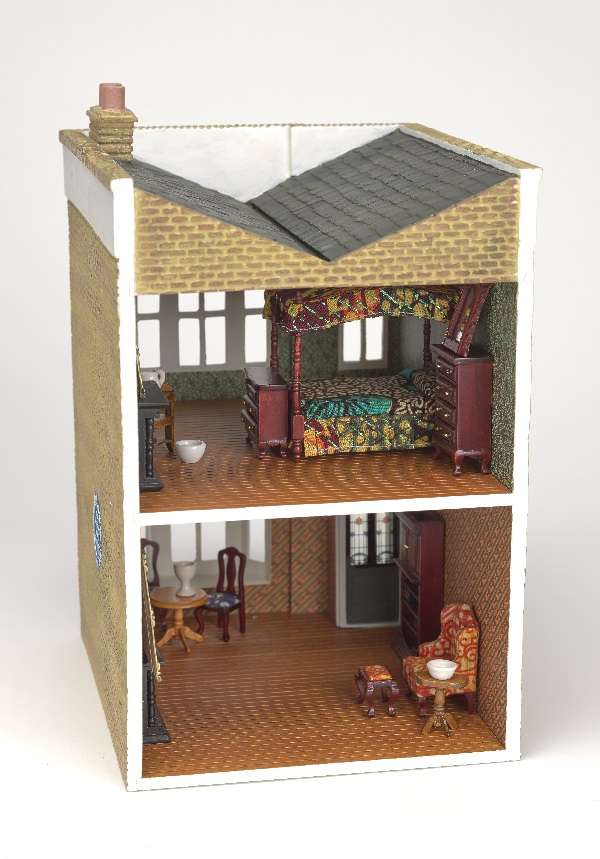

Marianela de la Hoz

(Mexican, b. 1965)Estoy Necesitado de Carne (I Am in the Need of Flesh), 2010

Egg tempera painting and mixed media assemblage

3 1/2 x 10 x 10 in

Gift of Pierrette Burbank Van Cleve. 2015.5. Image courtesy of the artist

Einar and Jamex de la Torre

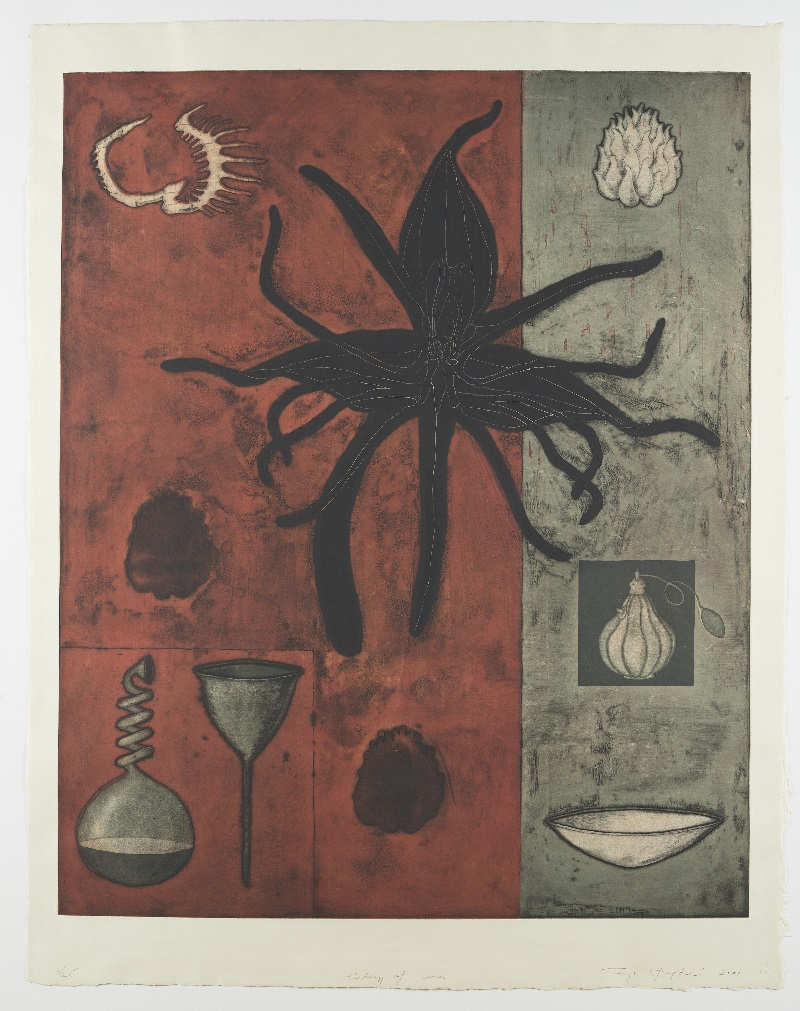

(Mexican, b. 1963 and 1960)Organ Exchange, 2011

Blown glass and mixed media

48 in. x 48 in.

Museum purchase from the Michel Roux Acquisition Fund. 2019.3. Image Courtesy of the artists and Koplin Del Rio Gallery

The Aztec calendar, toys, catholic figurines, mirrors, chains, plastic, glass, paper, glitter—this piece by Einar and Jamex de la Torre titled Organ Exchange contains as many materials as layers of meaning. Acquired for the museum’s permanent collection in 2019, on the occasion of their exhibition De La Torre Brothers: Rococolab, it brings together the world of kitsch and fine art. The carefully arranged conglomerate of objects and textures is emblematic of the De La Torre brothers’ unique aesthetic: contradictory, nuanced, bold, and, as they call it, maximalist. Einar and Jamex were born in Guadalajara, Mexico in 1963 and 1960 respectively. They moved to the U.S. at a young age and attended school in California, where eventually they studied art and discovered their passion for glassmaking. Currently, the artists live and work on both sides of the US-Mexico border with homes and studios in Ensenada and San Diego. Attuned to their experiences and surroundings, their artistic vision is informed by their experiences as Border artists whose identity is neither exclusively Mexican nor American, but instead enriched by both. The complexities of identity are at the core of the brothers’ creations; symbolism, history and humor are often the avenues they employ to examine them. In Organ Exchange the De La Torre Brothers examine the personal in the context of history and its collective implications.

Organ Exchange was inspired by the De La Torre Brothers’ experience with organ donation in 2001. After it was determined that a close relative needed a kidney transplant, the brothers were tested to find a match. The process led the artist-duo to create this work as a reflection on the value of the human body versus the value of its parts. The format evokes that of an Aztec calendar with a face in the center and the words “eat me” painted over the eyes. As we stand to observe the piece, our reflection is captured by several convex mirrors making us part of the work. Like cultural critics, Einar and Jamex oscillate between the personal and the political, the contemporary and the ancient, pointing out the irony of the new and the persistence of history. In their words: “Our art making process is sort of a laboratory where new compounds and hybrids are derived from vernacular cultural symbols.”

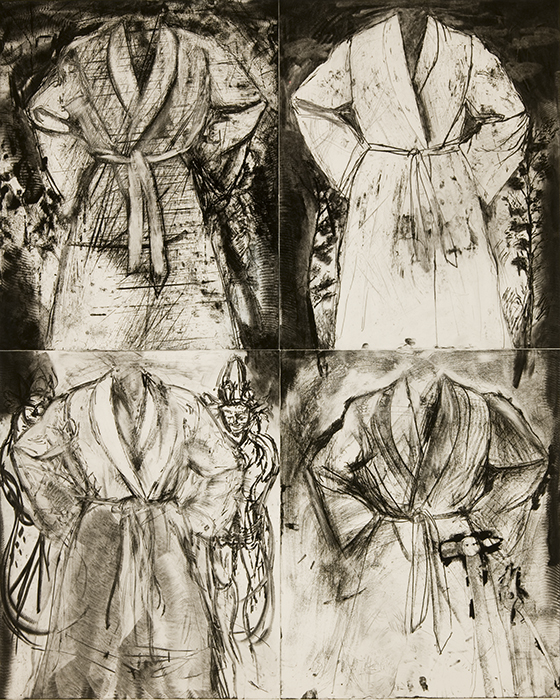

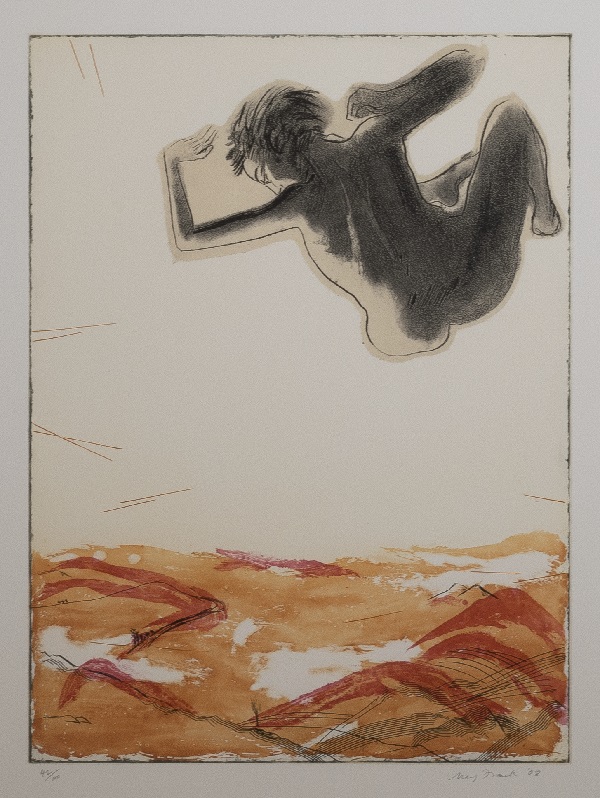

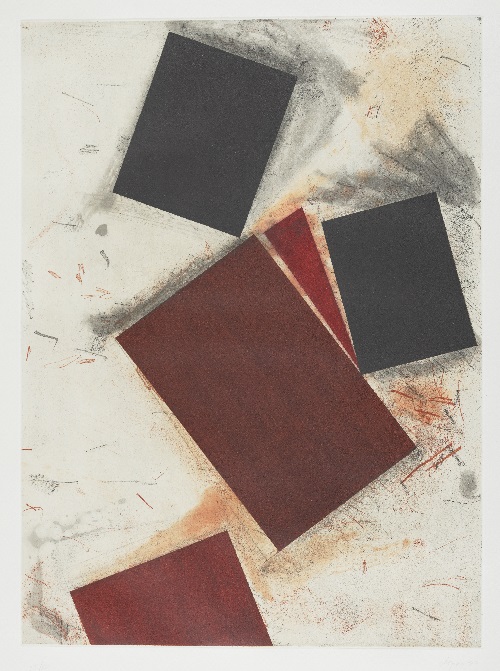

Jim Dine

(American, b. 1935)Blue Wash (Four Robes), 1991

etching with hand coloring

58 1/2 in. x 46 3/4 in. print

Purchased by the Friends and Partners of the Cornell Acquisitions Fund © Jim Dine/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 1992.3

Jim Dine first achieved recognition as part of the avant-garde Downtown scene in New York, experimenting with painting while also authoring and participating in Happenings at Judson Gallery and other artist-initiated, alternative art spaces in the Greenwich and East Village neighborhoods of Manhattan. Feeling out of place in the increasingly formalist and abstract avant-garde during the 1960s heyday of Minimalism, Dine moved, first to London—where he studied the work of Old Masters and temporarily abandoned painting in favor of drawing—and then to rural Vermont. During the 1970s he focused in particular on his printmaking, working in a variety of different print media, including lithography, etching, aquatint, woodcut, and a number of combinations thereof. Frequently working with master printmakers on both sides of the Atlantic, Dine began to push the limits of the medium, using not only traditional printmaker’s tools but also innovative ones, including power tools he purchased at hardware stores.

This print, which is notably large for an etching, highlights several of the features of Dine’s prolific printmaking practice. The image of the bathrobe reoccurs in his work from the 1960s to the 1990s, along with images of tools and other everyday objects. These repetitions caused Dine to be lumped in with the Pop Art movement, a connection he strenuously denies. Instead of the hard, shiny artifice of Pop, Dine sees these images as deeply personal, akin to self-portraits through the objects he holds close. Like many of his other prints, Dine released this one in a very small edition, in this case only 17. He frequently painted or otherwise altered individual prints, making them more like monoprints or even paintings than traditional examples of the medium.

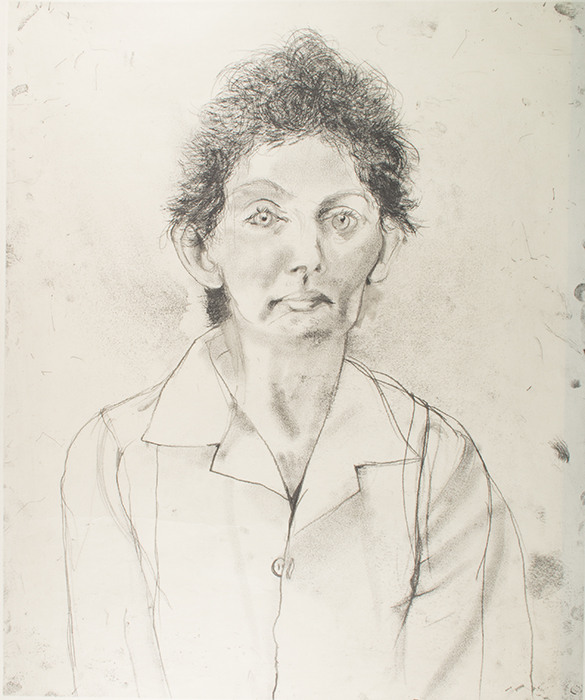

Jim Dine

(American, b. 1935)Nancy Outside in July I, 1978

Etching

23 1/4 in. x 19 1/2 in. print

Gift of Chauncey P. Lowe, 1997.4. © Jim Dine/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, NY

This print is the first in a series of twenty-five portraits of Dine’s wife Nancy, executed in collaboration with the legendary Parisian master printmaker Aldo Commelynck, who worked with Pablo Picasso among other artists. Dine describes Commelynck as one of his best friends in the world, and their collaboration resulted in a moving multifaceted portrait of Nancy Dine. Dine’s printmaking of the mid-1970s to the early 1980s was heavily invested in portraiture, especially of Nancy and himself, as well as a sharp linearity that contrasts with the voluptuous Expressionism of both earlier and later works on paper. The tangled tousle of Nancy’s hair, in which the artist seems to have rendered each individual strand, is reminiscent of his earlier studies of human hair, while the smudges of pigment that help delineate the contours of her face seem almost like Dine’s handprints on the plate.

As he developed the Nancy Outside series, which he referred to as his “etching symphony” Dine continually returned to this first image, reworking and repurposing the same plate as he continued to experiment with the technical limits of the printmaking medium. His desire to push etching as far as it could go was inspired by his love of German Expressionists, who similarly explored the possibilities of print.

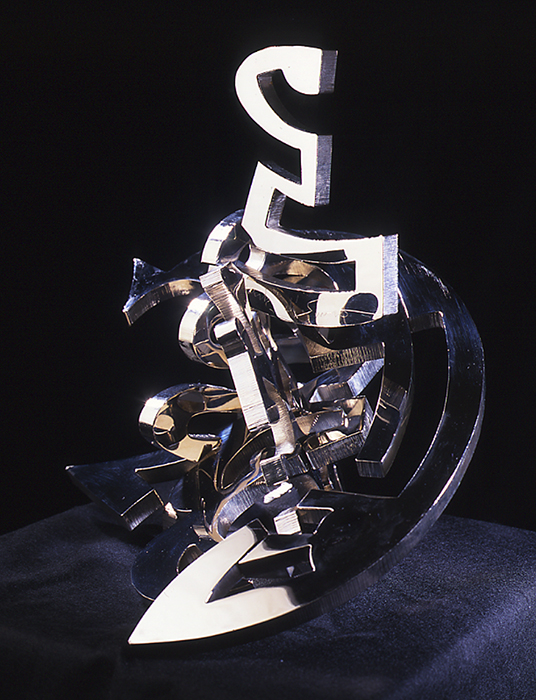

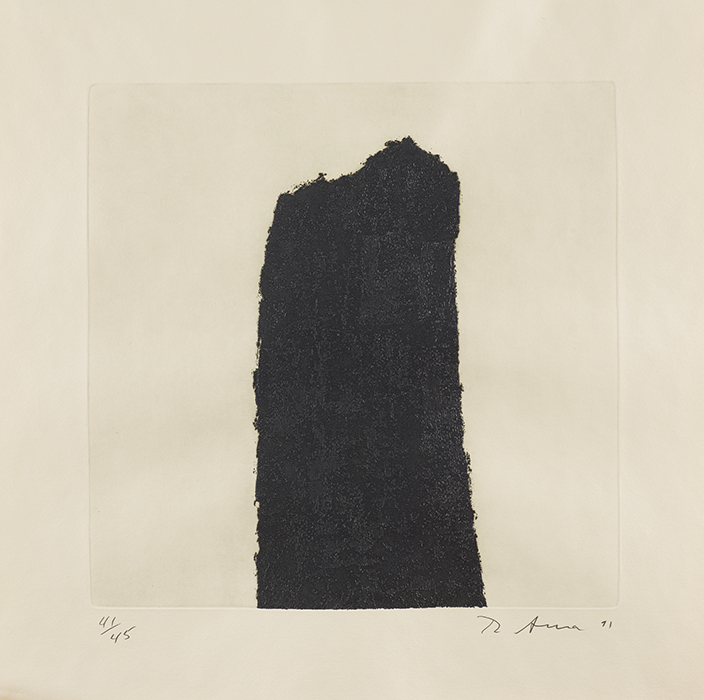

Mark di Suvero

(American, Shanghai, China, 1933 - )Moon Dog, 1981

nickel plated aluminum

19 in. x 16 in. x 5/8 in. sculpture

Purchased with the Friends and Partners of the Cornell Acquisitions Fund © Mark di Suvero, 1999.7

Mark di Suvero is best known for his monumentally scaled sculptures, which he first started making out of wood and other detritus found on the streets of post-industrial New York in the 1960s. After a construction accident left his legs paralyzed, he began to experiment with steel I-beams and other raw industrial materials, learning to use cranes and other heavy equipment in order to bend the massive components into their whimsical final forms. Di Suvero has long been interested in the concept of play, and frequently incorporates kinetic elements designed to attract viewers—including children—to engage with his work on a tactile as well as an intellectual level.

This sculpture, though much smaller in scale—di Suvero maintains that all of his work is human scale, reserving the term monumental for mountains and other geological formations—engages with the same themes. Part of a series of puzzles executed in collaboration with the legendary Gemini Graphic Editions Limited artist’s workshop and print studio in Los Angeles, Moon Dog reflects di Suvero’s interest in aluminum, titanium, and other “space age” materials during the 1980s. Created out of jigsaw-like interlocking pieces reminiscent of Chinese characters (di Suvero grew up in China), it can be arranged in a number of ways, including the vertical configuration shown in this photograph, which creates an interplay between right angles and smooth curves. Di Suvero—whose work is always abstract—chose the name while examining the piece under full moonlight, which must have emphasized its shimmering, luminous quality.

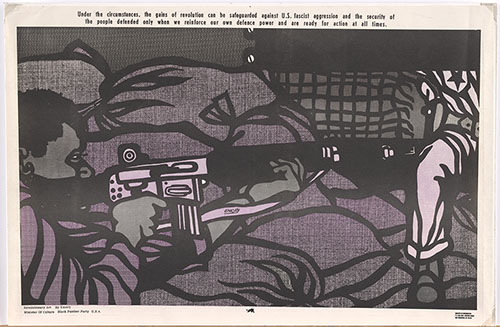

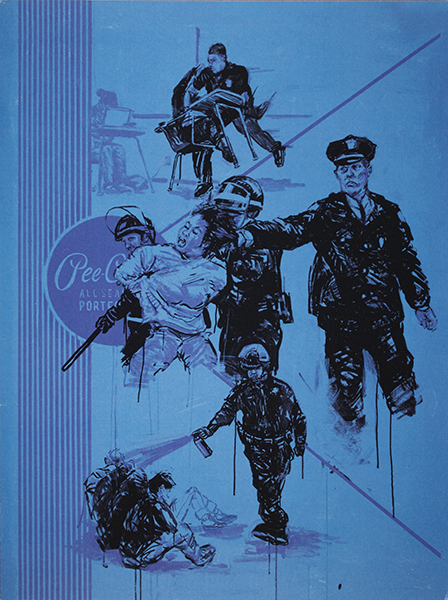

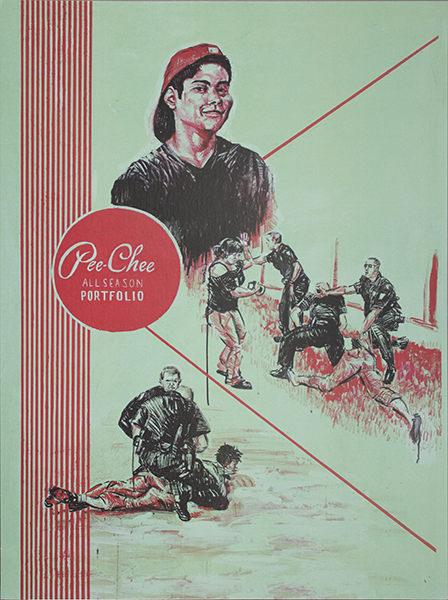

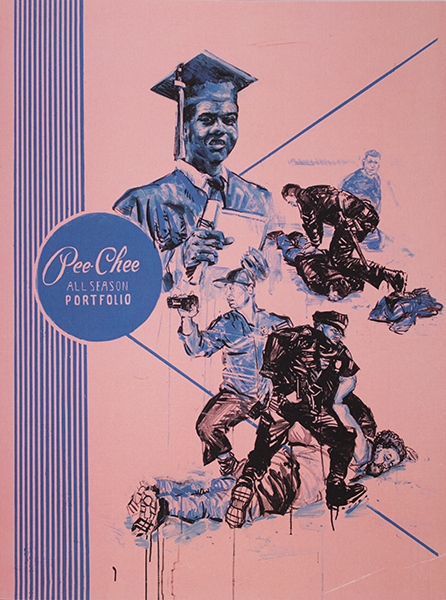

Emory Douglas

(American, b. 1943)Under the circumstances, the gains of revolution can be safeguarded against U.S. fascist aggression and the security of the people defended only when we reinforce our own defense power and are ready for action at all times., 1969

Offset lithograph on paper

15 x 22 3/4 in.

The Alfond Collection of Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2017.15.12 © Emory Douglas/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image courtesy of the artist.

Emory Douglas, who moved to San Francisco when he was eight, grew up in the segregated neighborhood of the Fillmore, where, like many African Americans of his generation, he was a frequent target of police harassment. At the age of twenty-one he enrolled in graphic design classes at City College in the city, and soon fell into the orbit of the playwright Amiri Baraka, who was undertaking a two-month artists’ residency at San Francisco State. Douglas designed sets for the writer, who introduced him to the crowd at the Black House, a cultural center at which he was staying during the residency. These residents included the actor and activist Danny Glover, as well as Eldridge Cleaver, who would become one of the founders of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, along with Bobby Seale and Huey Newton, who were frequent visitors to the Black House.

Douglas participated in several of the early Black Panther Party actions, including a 1967 armed demonstration at the California State House in Sacramento, after which he and most of the other Panthers were arrested. In aftermath of that event, as well as the murder of an unarmed teenager named Denzil Dowell by police in the East Bay city of North Richmond, the Panthers began to publish The Black Panther, a weekly underground newspaper which would come to have a circulation of over 100,000. Douglas soon took charge of the newspaper’s design and layout, and was named the BPP’s Minister of Culture, holding both roles until the early 1980s. At The Black Panther he adopted a style that blended the aesthetics of commercial art with leftist propaganda posters from Vietnam, Cuba, and the Middle East, using the newspaper and posters like these—based on images from the paper’s back page—to spread the BPP’s revolutionary message of Black self-reliance and self-defense.

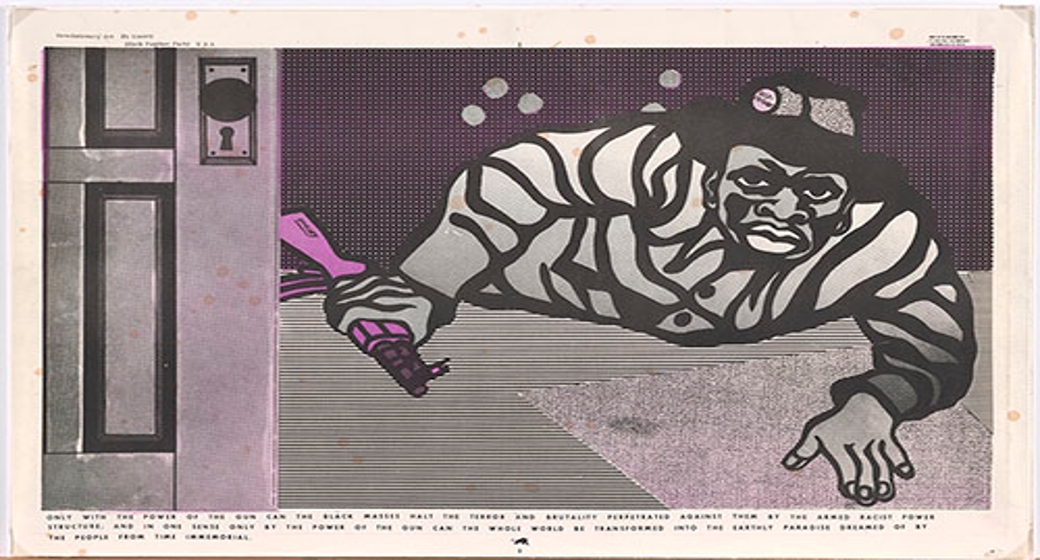

Emory Douglas

(American, b. 1943)Only with the power of the gun can the black masses halt the terror, 1969

Offset lithograph on paper

15 x 23 in.

The Alfond Collection of Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2017.15.11 © Emory Douglas/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image courtesy of the artist.

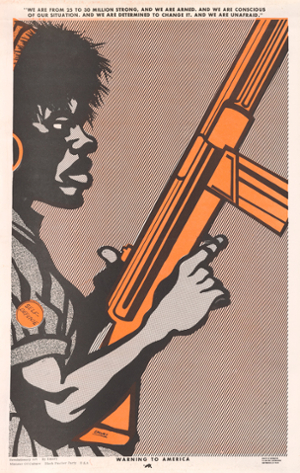

Emory Douglas

(American, b. 1943)Warning to America-We are 25-30 million strong, 1970

Offset lithograph on paper

22 x 14 in.

The Alfond Collection of Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2017.15.7 © Emory Douglas/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image courtesy of the artist.

Emory Douglas

(American, b. 1943)The Lumpen-The Heirs of Malcolm have picked up the gun , Offset lithograph on paper

22 x 14 in.

The Alfond Collection of Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2017.15.8 © Emory Douglas/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image courtesy of the artist.

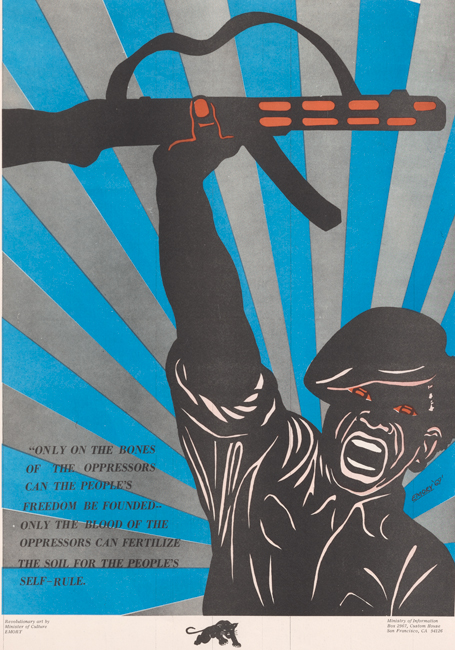

Emory Douglas

(American, b. 1943)Only on the Bones of the Oppressors can the People Freedom Be Found , 1969

Offset lithograph on paper

23 x 15 in.

The Alfond Collection of Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2017.15.10 © Emory Douglas/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image courtesy of the artist.

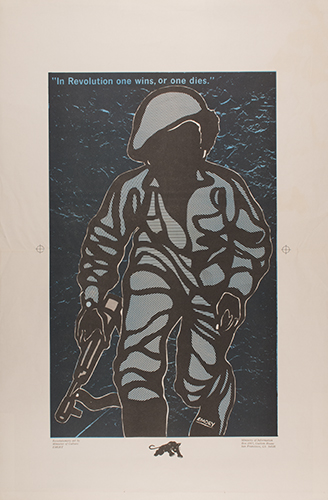

Emory Douglas

(American, b. 1943)In Revolution one wins, or one dies, 1969

Offset lithograph on paper

22 47/64 x 15 in. (57.73 x 38.1 cm)

The Alfond Collection of Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2017.15.9 © Emory Douglas/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image courtesy of the artist.

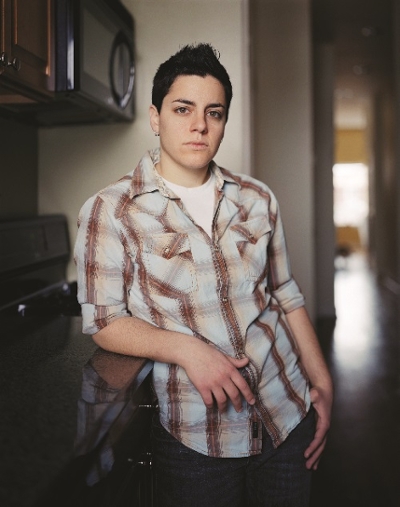

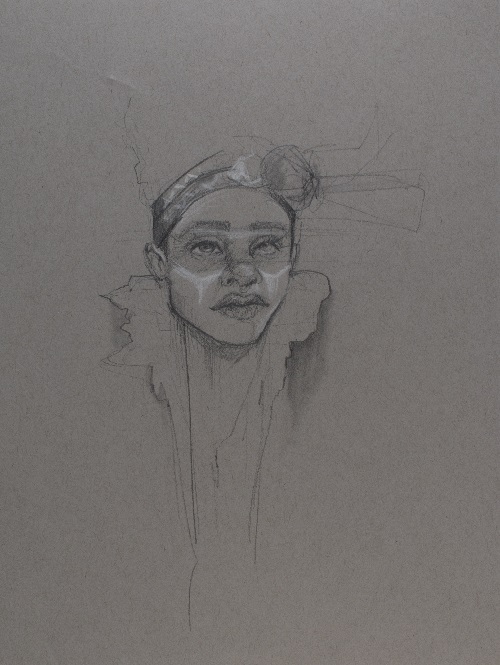

Jess T. Dugan

(American, b. 1986)Betsy, 2013

Pigment print

24 x 20 in.

Museum purchase with funds provided by the Diversity Council, Rollins College, 2014.6 © Jess T. Dugan

Jess T. Dugan is a photographer whose work largely focuses on members of the LGBTQ+ community. Betsy is a part of Dugan’s ongoing series Every Breath We Drew, which they started in 2011. In this series, Dugan depicts people with a variety of gender identities and sexual orientations, challenging the viewer to reflect on their own conceptions of identity. By revealing only the first name of the subjects and taking the pictures in personal spaces, such as their homes, Dugan encourages the viewer to connect with the subject(s) and look beyond their LGBTQ+ identity, seeing them as simply human. In many of their photographs the sitter gazes directly at the viewer. When you gaze back at Betsy, who do you see?

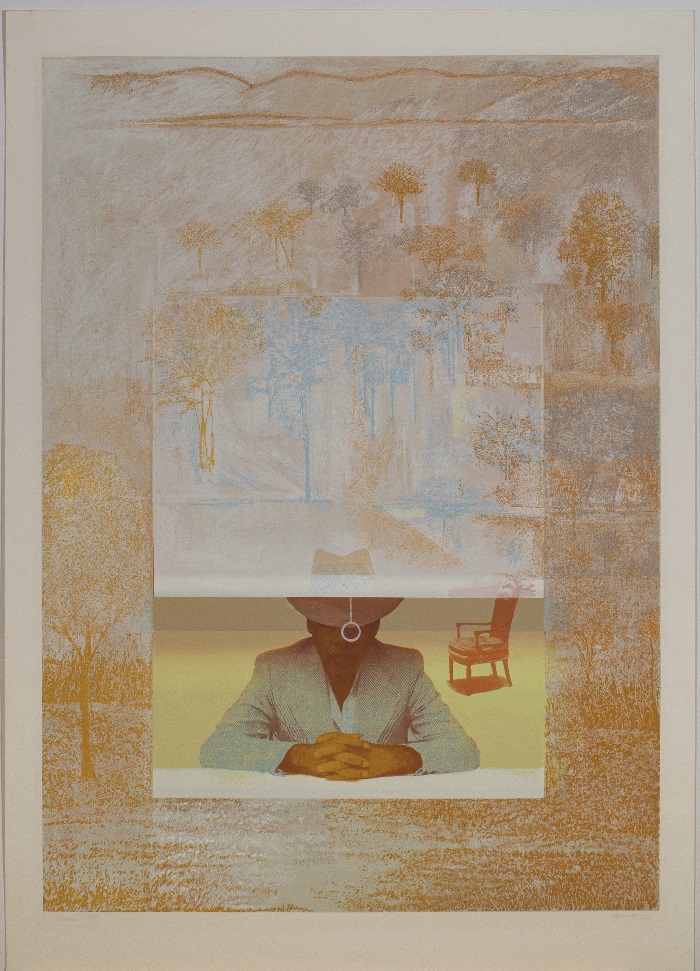

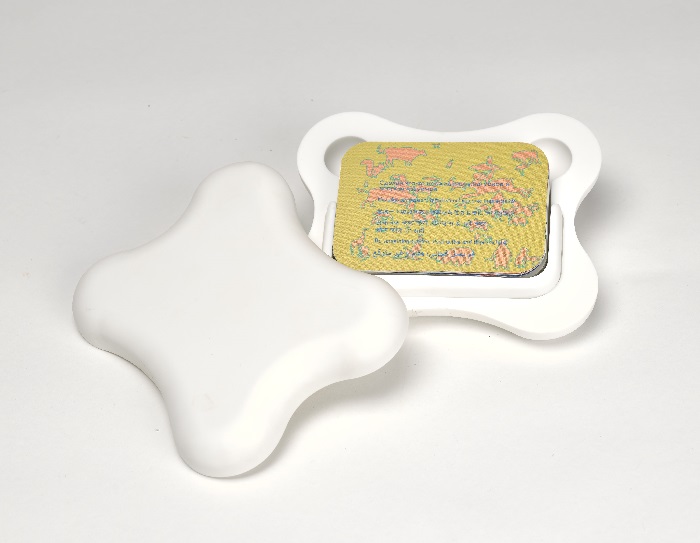

Brian Eno Peter Schmidt Pae White

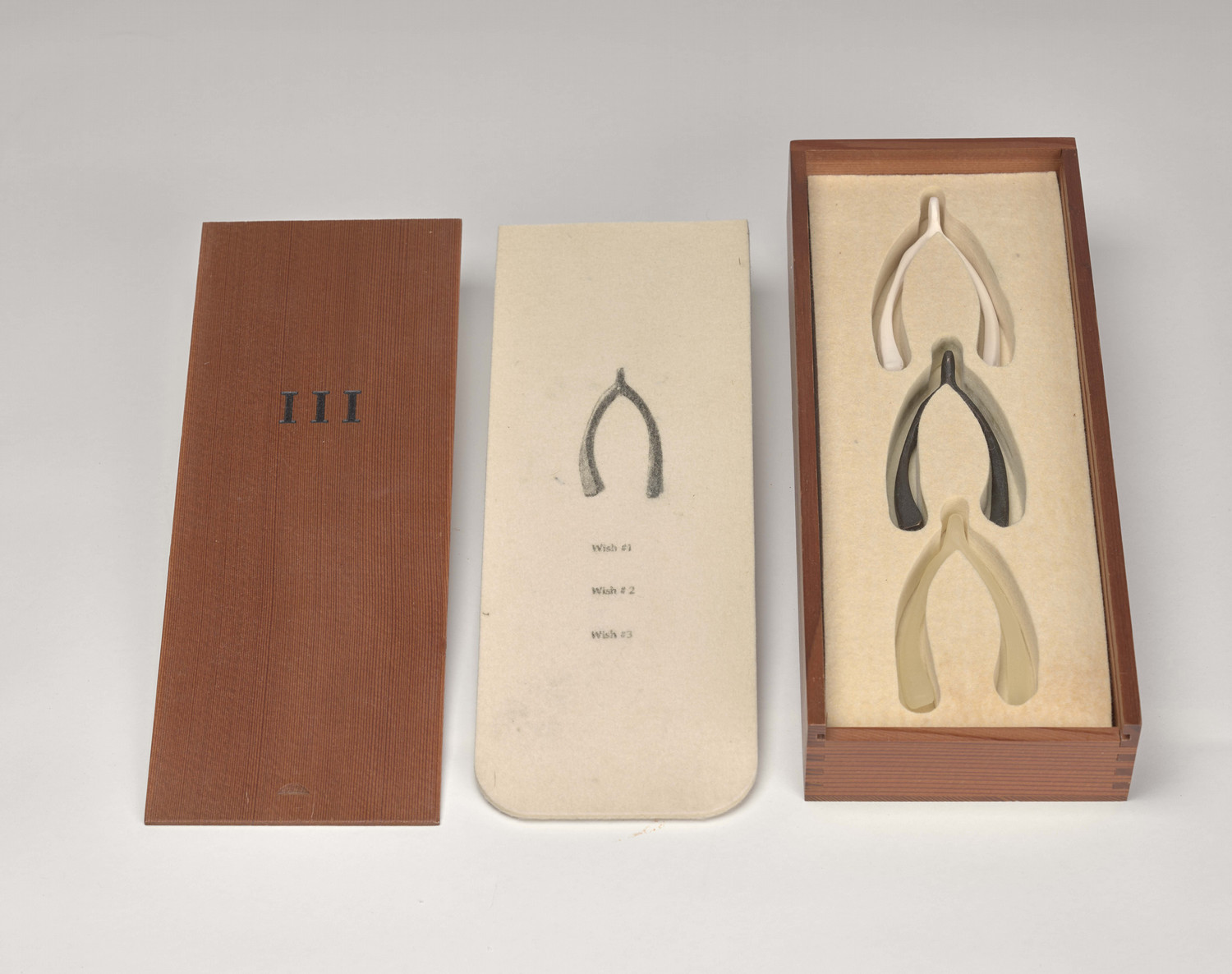

(British b. 1948), (British born Germany, 1931-1980), (American b. 1963)Oblique Strategies: One Hundred Worthwhile Dilemmas, 1996

Plastic and paper

5 ½ x 5 ½ x 1 ½ in. (closed)

Gift of Suzanne Delehanty in honor of Teagan Walsh, Rollins Class of 2020, 2020.39