Alfond Collection: Artists F-G

From Monir Farmanfarmaian to Sabrina Gschwandtner, explore the works of artists F-G in the Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art.

PLEASE NOTE: Not all works in the Rollins Museum collection are on view at any given time. View our Exhibitions page to see what's on view now. If you have questions about a specific work, please call 407-646-2526 prior to visiting.

Artists Featured in This Section

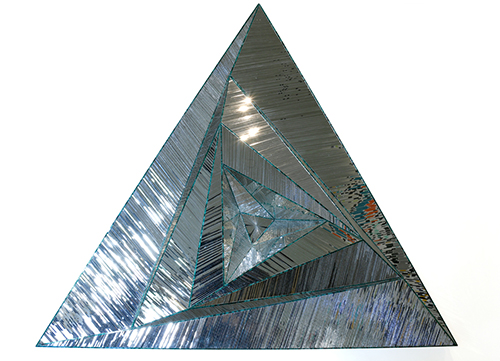

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian

(Iranian, 1922 - 2019)Second Family-Triangle, 2011

Mirror, reverse-glass painting, and plaster on wood

39 1/2 x 45 1/4 x 5 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2015.1.31 Image courtesy of the artist and Haines Gallery.

Known for her geometric drawings and mirrored mosaics, Monir Farmanfarmaian engages with traditions of Persian folk art and contemporary forms in her practice. In the early stages of her mirror works she had the help of master craftsman Hajji Ostad Mohammad Navid and continued to collaborate with skilled craftsmen throughout her career. Her process begins with a dream or an idea, then moves to a drawing that is shared with an architect who renders the work in 3D on a computer. The 3D rendering is transformed into a model, and the artist experiments with spatial relationships to create harmonious compositions. Each work starts with geometry, through which infinite possibilities are made. Viewers experience the possibilities in Farmanfarmaian's work in physical and metaphysical ways. The triangle in Islamic design symbolizes the intelligent human being and human consciousness. The artist attests that in Iran the mirror symbolizes water, water reflects light, and so the mirror is a sign of light and life. Her sculpture evokes this symbolism and evolves with the changing light and the reflections of each viewer.

Rodrigo Facundo

(Colombian, b. 1958)Crumbs, 2022

Acrylic on Canvas

63 3/4 x 79 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2023.1.15 © Rodrigo Facundo

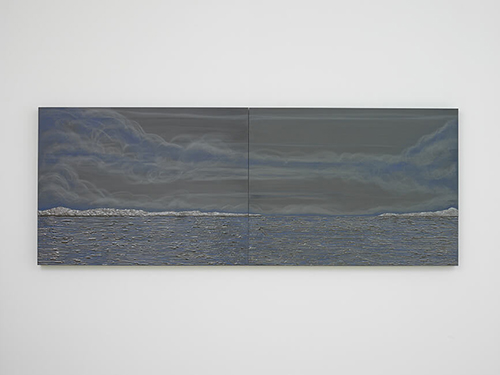

Teresita Fernández

(American, b. 1968)Nocturnal (Cobalt Panorama), 2012

Solid graphite on panel

36 x 48 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.71. © Teresita Fernández. Image courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong. Photo credit: Elizabeth Bernstein.

At the core of Teresita Fernández’s work is a paradox: she captures the essence of formless elements such as fire, water, and air using undeniably physical materials. She has become well-known for her large-scale public sculptures and installations made with such diverse materials as thread, aluminum, acrylic, plastic, and glass beads. All these familiar media share industrial origins, and yet they are transformed into shapes that suggest natural phenomena like waterfalls and sand dunes. This makes Fernández one of the latest in a long line of artists—many of them women—who have sought to reconcile the sublimity of nature with the technological present. Fernández complicates the viewer’s experience of her sculptures and drawings by frequently creating optical illusions of motion, dissolution, and illumination. By stressing metamorphosis and flux, she reveals that a viewer’s own subject position conditions how he or she experiences natural phenomena.

Although Nocturnal (Cobalt Panorama) (2012) is a conventional subject executed in the traditional medium of graphite on panel, the execution is far from traditional. This seascape expresses Fernández’s fundamental concern with replicating natural phenomena using mass-produced materials. The eye lingers over her varied graphite marks, which alternately describe thin, wispy clouds and thick, frothy waves. The insistent materiality of these surface treatments is at odds with the vast, unfolding vista of her seascape. Fernández opens up the center of the drawing by pushing the dense accumulations of clouds and sea foam to either end of the narrow panel. As a result, the two-dimensional picture plane disappears in order to open up a window into a third dimension, granting the viewer visual access to an infinite horizon. The swirling curves of the clouds and the staccato whitecaps of the ocean imply a sense of motion as they pull the viewer’s gaze across the length of the sweeping scene. Fernández’s self-consciously framed composition points to the ways in which our experience of the landscape is already determined by our own position as viewers.

--Sarah Parrish

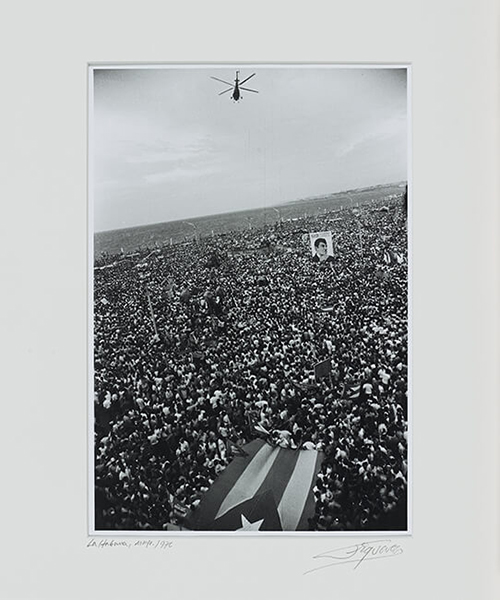

José A. Figueroa

(Cuban, b. 1946)De la serie Esa Bandera, La Habana, mayo de, 1970

Silver gelatin print

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2014.1.45. © José A. Figueroa. Image courtesy of the artist.

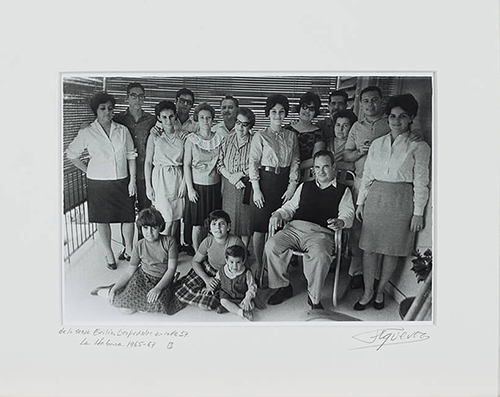

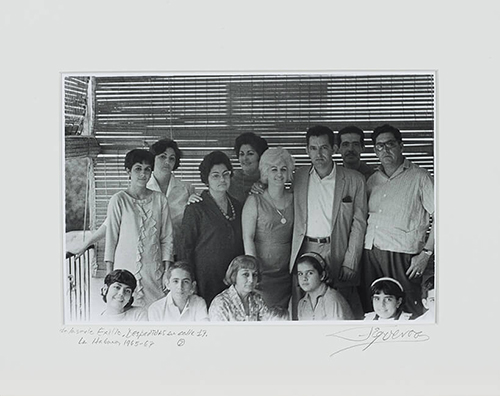

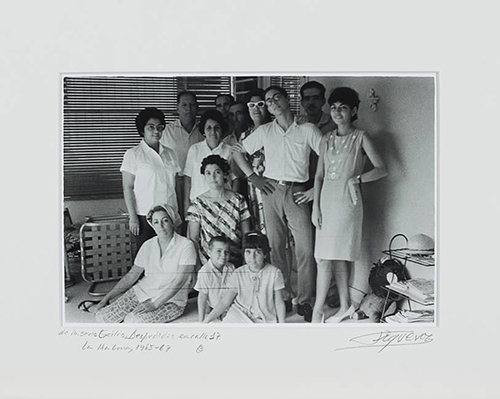

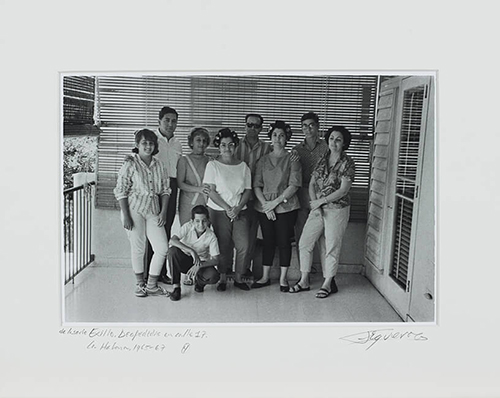

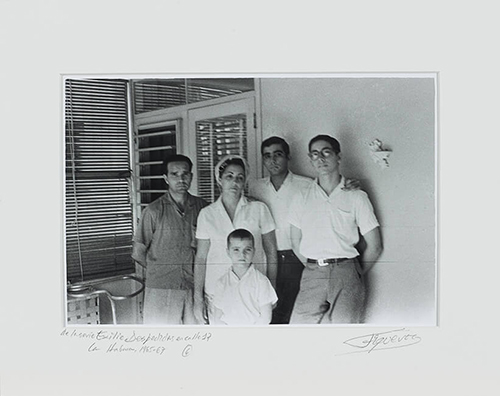

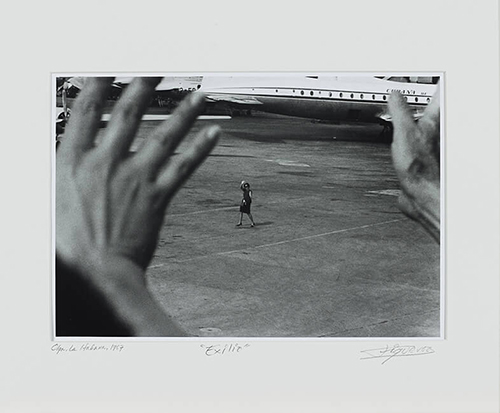

Some of Figueroa’s images are entirely domestic, scenes of friends and family. Others record critical events in his country’s history, political protests or notable figures. The best, however, hover between these two registers. Olga (1967) catches the photographer’s own hand as he waves goodbye to his mother, about to board a waiting plane. Part of his Exile series, depicting the ongoing departure of family members for Miami as the political climate changed, Olga captures in one glance both a deeply private portrait and a sociopolitical commentary. The image testifies to Figueroa’s unique ability to make the intimate resonate on a larger scale and to find the personal within the historical.

--Kelly Presutti

José A.Figueroa

(Cuban, b. 1946)De la serie Exilio. Despedidas en calle 17. La Habana (Part 1), 1965–1967

Silver gelatin print

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2014.1.51.1-6. © José A. Figuero. Image courtesy of the artist.

José A. Figueroa

(Cuban, b. 1946)De la serie Exilio. Despedidas en calle 17. La Habana (Part 2), 1965–1967

Silver gelatin print

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2014.1.51.1-6. © José A. Figueroa. Image courtesy of the artist.

José A. Figueroa

(Cuban, b. 1946)De la serie Exilio. Despedidas en calle 17. La Habana (Part 3), 1965–1967

Silver gelatin prints

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2014.1.51.1-6. © José A. Figueroa. Image courtesy of the artist.

José A. Figueroa

(Cuban, b. 1946)De la serie Exilio. Despedidas en calle 17. La Habana (Part 4), 1965–1967

Silver gelatin print

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2014.1.51.1-6. © José A. Figueroa. Image courtesy of the artist.

José A. Figueroa

(Cuban, b. 1946)De la serie Exilio. Despedidas en calle 17. La Habana (Part 5), 1965–1967

Silver gelatin print

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2014.1.51.1-6. © José A. Figueroa. Image courtesy of the artist.

José A. Figueroa

(Cuban, b. 1946)De la serie Exilio. Despedidas en calle 17. La Habana (Part 6), 1965–1967

Silver gelatin prints

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2014.1.51.1-6. © José A. Figueroa. Image courtesy of the artist.

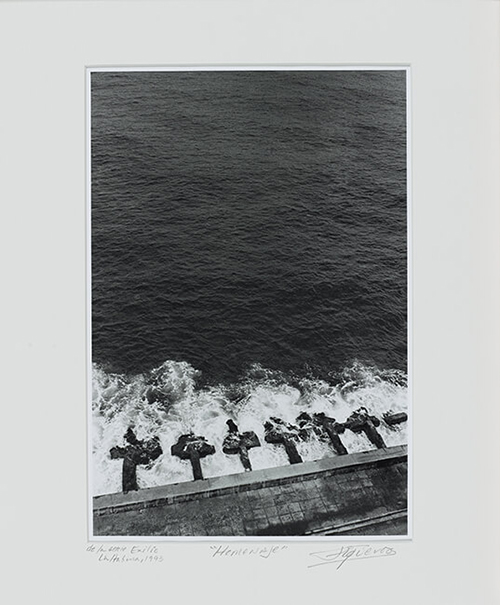

José A. Figueroa

(Cuban, b. 1946)De la serie Exilio. Homenaje, La Habana, 1993

Silver gelatin print

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2014.1.46. © José A. Figueroa. Image courtesy of the artist.

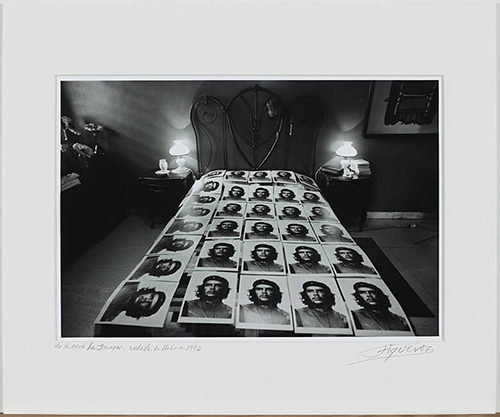

José A. Figueroa

(Cuban, b. 1946)De la serie La Imagen. Vedado, La Habana, 1992

Silver gelatin print

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2014.1.48. © José A. Figueroa. Image courtesy of the artist.

Perhaps the most iconic image of the Cuban Revolution, the portrait of Che Guevara taken by master photographer Alberto Korda, mentor to the artist José A. Figueroa, makes an appearance in the latter’s 1992 photograph Vedado. Dozens of prints of the Che image are spread across a small bed, flanked by a pair of nightstands holding glowing lamps, an alarm clock, a stack of books. The revolutionary import of Che’s portrait contrasts with the comfortable domesticity of the scene, taken in Figueroa’s apartment in the well-off Vedado neighborhood of Havana. This contrast fittingly renders a tension that is felt across Figueroa’s oeuvre, where the Cuba he shows us is not always the one we expect to see, and scenes of revolt alternate with images of quiet everydayness.

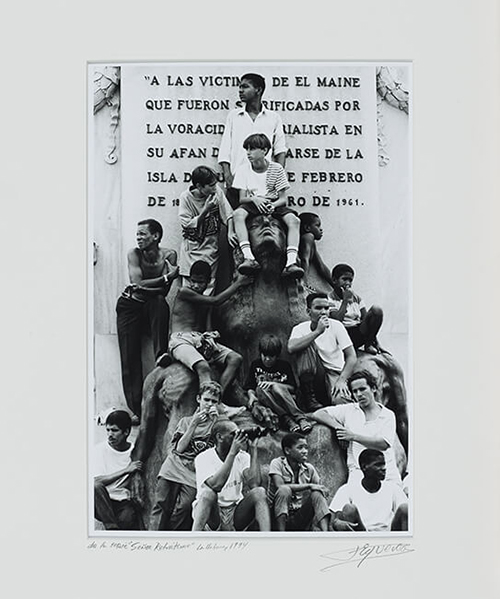

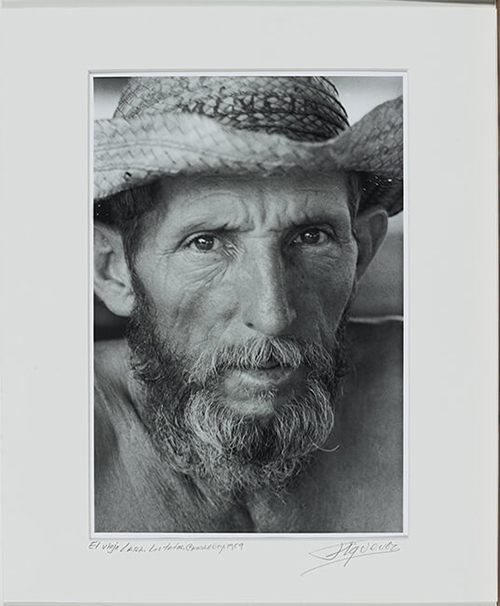

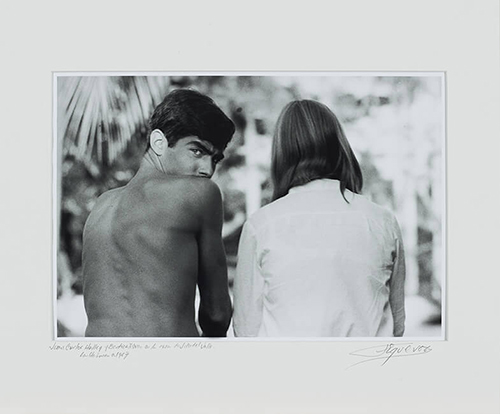

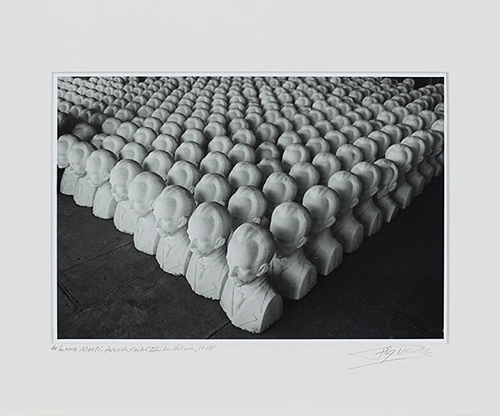

The selection of photographs by Figueroa in the Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art gives a picture of Cuba over four decades. For US Americans, these offer a glimpse into the evolution and nuance of a place that has remained, until recently, inaccessible to our gaze and thus static in our perception. Born in Havana in 1946, Figueroa worked in the sixties as a studio assistant to Korda. He began taking his own photographs then, and after the government appropriated Korda’s studio, worked as a photojournalist. Figueroa has since continuously recorded his perspective on the country, generating what he terms “a Cuban self-portrait,” a body of work that is at once an individual record and a historical document.

--Kelly Presutti

José A. Figueroa

(Cuban, b. 1946)De la serie ¡Señor retráteme! La Habana, 1994

Silver gelatin print

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2014.1.49. © José A. Figueroa. Image courtesy of the artist.

José A. Figueroa

(Cuban, b. 1946)El viejo Lara. Los Tatos, Camagüey, 1969

Silver gelatin print

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2014.1.44. © José A. Figueroa. Image courtesy of the artist.

José A. Figueroa

(Cuban, b. 1946)Juan Carlos Halley y Bertica Riva en la casa de Julio del Valle, c. 1967

Silver gelatin print

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2014.1.43. © José A. Figueroa. Image courtesy of the artist.

José A. Figueroa

(Cuban, b. 1946)De la serie Exilio. Olga, La Habana, 1967

Silver gelatin print

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2014.1.50. © José A. Figueroa. Image courtesy of the artist.

José A. Figueroa

(Cuban, b. 1946)De la serie Marti. Avenida Carlos III La Habana, 1988

Silver gelatin print

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2014.1.47. © José A. Figueroa. Image courtesy of the artist.

Mark Flood

(American, b. 1957)Mirror, Mirror, 2012

Acrylic on canvas

96 x 52 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.121. Image courtesy of the artist and Zach Feuer Gallery, New York.

The title of Mark Flood’s Mirror Mirror (2012) is an obvious allusion to the Evil Queen’s refrain in the classic fairy tale Snow White. Just as this villain asked her mirror, “Who is the fairest of them all?,” Flood’s lace paintings pose questions about traditional standards of beauty. In this series, which he began in the early 2000s, Flood drenches torn lace in acrylic paint and stamps it onto canvas. The resulting marbled patterns juxtapose discordant, garish colors that violate the harmonies of orthodox color theory. The painterly violation of this chosen material likewise pushes the boundaries of good taste, since lace invites associations with wedding gowns, lingerie, curtains, and tablecloths. Further, by introducing these decorative elements into his paintings, Flood overturns the entire tradition of modern abstraction that strove to separate high art from kitsch. His lace paintings propose an alternative model of beauty that defies formalist doctrine.

Despite lace’s ideological baggage, Flood defamiliarizes the material so that it no longer looks like fabric, but instead resembles aerial maps, geological strata, foliage, or feathers. This profusion of incompatible references has a destabilizing effect that makes it impossible for the viewer to establish a sense of scale: one could just as easily be looking through a microscope or a telescope. Flood further plays with the viewer’s perceptions by leaving a disconcerting void in the center of many of his paintings, as he does in Mirror Mirror. A field of metallic silver paint makes this canvas resemble a mirror, providing a symbolic space where one can reflect on the themes of beauty, vanity, and identity, particularly as they relate to the act of painting itself.

Flood attacks the elevated tradition of abstract painting with a subversive, countercultural attitude that has defined his artistic career since it began in the 1980s. During that decade, he performed with his band Culturcide, whose punk-rock aesthetic also informs his visual art from the period. He critiqued American popular culture by creating grotesque collages of celebrity photographs, scrawling obscene slogans over advertising logos, and by sending decoys to his exhibition openings instead of attending himself. Along with his lace paintings, these radical gestures prove that no aspect of high art or lowbrow culture is immune from Mark Flood’s witty, incisive interventions.

--Sarah Parrish

Rinaldo Frattolillo

(American, b. 1935)Mr. Goodbar, 2007

Screenprint

35 x 60 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.63. Image courtesy of the artist.

The work of New York-based artist Rinaldo Frattolillo cleverly plays with words and concepts based on both popular culture and the art world. His diverse artistic practice comes out of the legacy of 1960s Pop Art through his choice of common, everyday objects and motifs as the source of his humorous paintings, prints, and sculptures. He often hones in on common conceits around the themes of love and lust. The artist works in different media—including bronze, Belgian linen, corrugated steel, photography, acrylic, wood, plastic, barbed wire, glass, and granite—to visualize these tropes with ironic and amusing twists. His aim is to amuse and provoke viewers so they are prompted to reconsider what they are seeing.

Frattolillo’s use of irony is especially potent. His work is critical of religion, the state, politics, and especially art. Deflating elevated concepts in a reverse alchemical process, he cynically makes apparent the realities of the art market. For example, the same year the contemporary British artist Damien Hirst created the diamond-encrusted skull entitled For the Love of God (2008), Frattolillo mockingly debuted Damius Chocolatechipus – a skull covered with chocolate chips. Frattolillo converted Hirst’s extravagant, precious materials into cheap, digestible objects.

In Mr. Goodbar (2007), Frattolillo represents the well-known packaging of the Toblerone chocolate bar, rebranding it “Testosterone.” It takes the viewer a second glance to notice the difference, as the size and typeface are exactly the same as the original wrapper. In renaming the chocolate bar, Frattolillo draws attention to the object’s phallic attributes: its elongated shape as well as the macho packaging. As pictured in this work, one end of the chocolate bar is open and the foil is pulled back, exposing the dark and tempting interior and inviting the viewer to take a bite. Libido and lust are bound to gustatory pleasure, here made readily available in one sexy package. Like Fratolillo’s other works, Mr. Goodbar sardonically points to the commodification of human pleasure in the modern world. Everything is for sale and easily replicated in infinite multiples, be it chocolate, sex, or art. Even the medium itself—silkscreen—refers to the easy reproducibility of the art object.

--Martina Tanga

Robert Freeman

(American, b. 1946)Marco Polo, 2021

oil on canvas

88 1/2 x 70 1/2 x 2 1/2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2021.1.12 © Robert Freeman

Jessie Homer French

(American, b. 1940)Approaching Flames, 2021

Oil on plywood

12 x 32 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ‘68 and Theodore ‘68 Alfond., 2021.1.31 © Jessie Homer French

Jeremy Frey

(Native American, Passamaquoddy, American, b. 1978)Urchin, 2023

Black ash, sweet grass, synthetic dye

5 x 11 ½ x 11 ½ in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond. 2023.1.31 © Jeremy Frey

Artist Jeremy Frey descends from a long line of Passamaquoddy basket weavers, an Indigenous group located in Northern Maine. Basketry is a “core mode of cultural expression” for the Passamaquoddy, and Frey learned traditional weaving methods from his mother. Like other Passamaquoddy weavers, Frey foraged the natural materials of sweetgrass and black ash tree from his natural environment to create this work. This basket’s short stature and sharp spikes reflect the sea creature giving this traditional Passamaquoddy basket shape its name, the sea urchin. Still, Frey modernizes his practice by highlighting the striking form with a rich red and black coloration, creating “a newer and more elaborate version of my work each time I weave.”

This basket reflects the contemporary emphasis on sculptural materiality and repetitious form, builds upon the historical narratives of northern Indigenous basket-weaving, and reveals the deep ecological understanding needed to practice this craft.

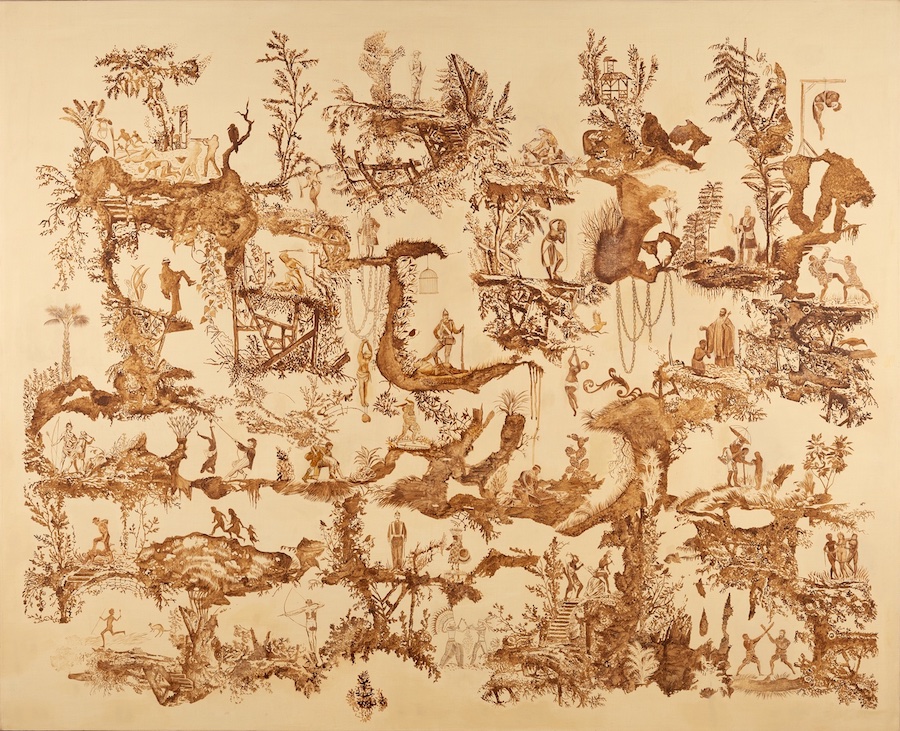

Gonzalo Fuenmayor

(Colombian, b. 1977)God Bless Latin America, 2013

Charcoal

44 1/2 x 94 1/2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.140. Image courtesy of the artist and Dot Fiftyone Gallery, Miami.

Gonzalo Fuenmayor demonstrates his affinity for both the Colombian and American aspects of his identity through his ironic charcoal drawings and photographs. A native of Barranquilla, Colombia, a former student at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and a practicing artist in Miami, Fuenmayor has a personal stake in the dialogue of transnationalism in the twenty-first century. As a result, he is well versed in topics of identity, language, culture, commerce, financial interdependence, immigration, and the growing emergence and influence of Latino culture in the United States. In God Bless Latin America (2013) he merges a well-known North American logo with a written reference to Latin America to propose new insights into this dialogue of transnationalism. Fuenmayor points to a broader multiculturalism that stems from the ubiquity of the Spanish language throughout the United States, the integration of Latin rhythms into the music industry, and the increasing popularity of Latinos in Hollywood film productions.

Appropriating the phrase “God Bless America” along with a logo for the prominent 20th Century Fox Film Company, Fuenmayor emphasizes the growing presence of Latino culture in the United Sates and its impact on American pop culture. With a witty tone typical of the artist’s body of work—a light-heartedness reminiscent of Dada artists—Fuenmayor’s God Bless Latin America provides the viewer a space in which to engage with the art formally while addressing significant cultural issues. Through his skillful manipulation of charcoal, Fuenmayor momentarily convinces the viewer that his representations are faithful copies of their source images. In other works, he maintains the trompe l’oeil effect while also reflecting the qualities of magical realism popular in Latin American literature, and made famous by authors such as Gabriel García Márquez. In both cases, Fuenmayor’s mastery of light and shadow contributes to the power of the image, and serves to heighten the aesthetic beauty of the drawing as well as to pull the image closer to our reality.

Fuenmayor’s work speaks to the history and the lasting influence of colonialism on both Northern American and Latin American societies. His other drawings and photographs range from exaggerated images of the iconic fruit-laden headdresses of Carmen Miranda, a reference to European-controlled, and often brutal banana market, to depictions of Victorian-era chandeliers and decorative furniture, aesthetic imports from Western Europe still found throughout the southern hemisphere. As a whole, his work recalls the complicated, intertwined relationship between Latin America and North America and its impact on all aspects of society, from economics to culture. Emblematic of the effort to embrace diversity in Northern American culture, artists like Fuenmayor have generated a sort of visual bilingualism, recognizing the blending of cultures and traditions as manifested in the arts.

Morgan Metzger

Click here to view a Conversation with Gonzalo Fuenmayor

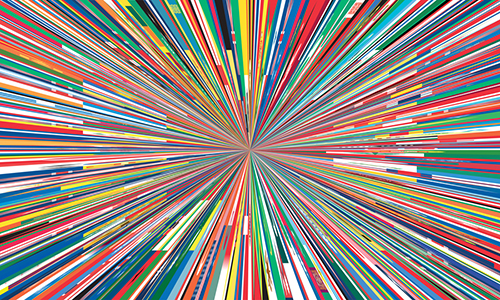

Meschac Gaba

(Beninese, b. 1961)Citoyen du Monde, 2012

Inkjet print on synthetic canvas

111 6/64 x 196 27/32 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2017.6.47. © Meschac Gaba. Image courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg.

Since the 1990s, Meschac Gaba’s diverse media work and interactive installations have explored themes of globalization, ecology, migration, and power. Gaba’s practice is often inspired by his bicultural experiences between the Netherlands and his native Benin in West Africa. He frequently examines the relationship between Africa and the West, and the preconceived notions of local and global identities. This work, comprised of all the world’s flags, creates his vision for a global flag. The designs of each flag, abstracted and arranged together seamlessly, converge in a central point. The harmonious composition symbolizes the world’s people coming together, and the notion of national melding into international in the age of globalization.

Meschac Gaba

(Beninese, b. 1961)Souvenir Palace: Cricket Bats, 2014

Oil paint on wood

16 1/4 x 3 x 1/2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2014.1.40. Image courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York.

Benin-born Meschac Gaba balances multiple identities: he is an African as well as a European, an artist as well as a curator, and in his multimedia installation Souvenir Palace, he is an entertainer as well as a diplomat. Souvenir Palace, which premiered at the 2010 Liverpool Biennale, stages a game room replete with billiard tables, coin canisters, and other tchotchkes. All these amusements are emblazoned with flags from around the world, while the Union Jack provides a bold backdrop on the surrounding walls. In the context of the biennial, Souvenir Palace functioned as a microcosm of the broader tourist spectacle of the exhibition itself, serving to delight visitors with a profusion of cultural exports from around the world.

Gaba’s display included a group of seven miniature cricket bats, each patterned with the flag of a different nation. Are we to understand these bats as toys, weapons, or works of art? On an aesthetic level, the patterns and colors of the flags become visually compelling abstractions. Yet these rough, handmade objects are far from precious, beckoning viewers to pluck them off their pedestals and begin a provisional cricket match with other visitors in the museum or gallery. This absurd playing field poses obvious problems, as does the undersized scale of the bats. Moreover, their heterogeneous markings make it difficult to form teams. How can one compose teams if each bat represents a different nation? Is this variety intended as a symbol of diversity or divisiveness? Though the Souvenir Palace Cricket Bats are playful in the most literal sense, their veneer of teamwork and sportsmanship is belied by critical undertones of rivalry and competition.

The sport of cricket thus becomes a metaphor for geopolitics. By entering the Souvenir Palace and engaging in its activities, we are invited to reconsider who is allowed to play the game of global diplomacy—and what is at stake for the winners and losers. These themes recur across Gaba’s mixed-media practice, which interrogates issues of nationalism, economics, and globalization in relation to the contemporary art market. Much like Souvenir Palace, his best-known project—the widely exhibited Museum of Contemporary African Art—draws on a carefully curated constellation of paintings, sculptures, and interactive games to pose provocative questions about national identity.

--Sarah Parrish

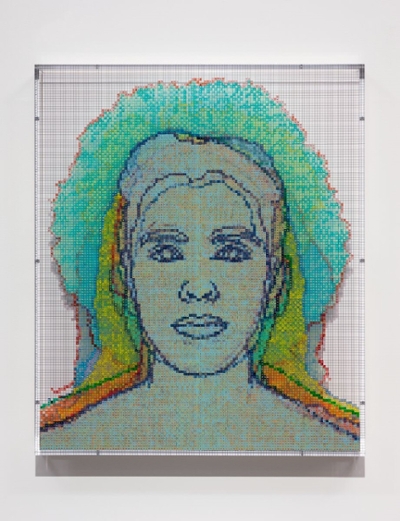

Charles Gaines

(American, b. 1944)Numbers and Faces: Multi-Racial/Ethnic Combinations Series 1: Face #11, Martina Crouch (Nigerian Igbo Tribe/White), 2020

Acrylic paint, acrylic sheet and photograph

38 x 32 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2021.1.4 © Charles Gaines. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Matthew Gamber

(American, b. 1977)Stanford Bunny (x1), 2012

Digital c-print

30 x 40 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.97. Image courtesy of the artist and Gallery Kayafas, Boston.

Matthew Gamber is a Boston-based artist interested in testing photography’s capacity to faithfully document our material world. His investigations into the science of sight and perception trouble the camera’s lauded history as a truth-telling device. In a recent series, Any Color You Like, Gamber photographed a range of objects whose primary function is to describe, draw our attention to, or test our reactions to color, such as the SMPTE color bars used to test video signals, 3D glasses, and the Farnsworth Munsell 100 Hue Test commonly administered to evaluate color vision. While these items were photographed with color film against a simple white background, the files were converted to black and white negatives and printed as traditional silver gelatin black and white prints in the darkroom. Drained of color and therefore function, the objects appear as scientific test subjects, documented and relegated to some dusty slide library. Thus transformed, Gamber’s “straight” black and white photographs of color sensory tests invite speculation into how we believe we perceive color, and suggest photography’s ability to misinform.

Gamber’s Stanford Bunny (x1) (2012) and Stanford Bunny (x2) (2012) are an extension of the Any Color You Like series. The rounded, stylistic bunnies seem more at home in a cultivated garden than they do in the science and computer graphics fields. However, the represented rabbit, also known as the “Stanford Bunny,” is one of the most commonly used test models in computer graphics. Developed by Greg Turk and Marc Levoy in 1993 when they were postdoctoral scholars at Stanford University (hence the bunny’s name), the testing model was made with laser scans of a 7.5-inch terra cotta garden statue. The translation of this 3D object into a set of data points—later made publicly available on the Internet—allows graphics designers to test their own algorithms. Similar to the examples mentioned earlier, the “Stanford Bunny” is an evaluation model, but instead of assessing color, it tests virtual three-dimensionality. Doubled and situated in a bright aquamarine blue, or with its back turned in a sunny peach tone, Gamber’s photographs revive the “Stanford Bunny” and give physical form back to the data set after 20 years. In doing so, he questions its true form—kitsch object? data object? graphics icon?—as well as the ability of photography to complicate representation. Instead of using a camera to render these images, Gamber worked with the data file to compose the rabbits. Are we seeing an accurate 2D printout of the original 3D model that has become internationally known, or an abstraction of that data set? Posing the question of what is the original and what is the copy, Gamber challenges photography’s historic role as arbiter of truth, arguing for the agility and slipperiness of the medium.

--Lexi Lee Sullivan

Matthew Gamber

(American, b. 1977)Stanford Bunny (x2), 2012

Digital C-print

30 x 40 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.96. Image courtesy of the artist and Gallery Kayafas, Boston.

Ori Gersht

(Israeli, b. 1967)On Reflection, Material E23 (After J. Brueghel the Elder), 2014

Light jet print mounted on Dibond

87 1/2 x 73 1/2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2015.1.13. Image courtesy of the artist and CRG Gallery, New York.

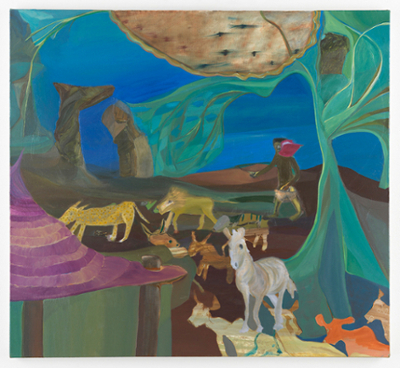

Ficre Ghebreyesus

(Eritrean, 1962-2012)Shepherd, ca. 2002-07

Acrylic on canvas

50 1/2 x 54 5/8 x 2 1/2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2020.1.3. © The Estate of Ficre Ghebreyesus. Image courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co., New York

Ficre Ghebreyesus’ explorative, abstracted works reflect aspects of his global experience and personal narrative. He left his home of Eritrea as a political refugee from the Independence War (1961-1991), and lived in Sudan, Italy, and Germany, before he settled in the United States. He studied painting at the Art Students’ League and printmaking at Bob Blackburn Printmaking Workshop before earning his MFA from Yale University. Although Ghebreyesus created a significant body of work, he seldom exhibited his work during his lifetime. His paintings, often dreamlike, full of rich jewel-toned colors, patterns, and textures, elicit storytelling. This work, typical of his style, features a whimsical landscape with a shepherd in the middle-ground herding a diverse group of animals towards the foreground of the painting.

Jeffrey Gibson

(Native American, b. 1972)Constellation, No. 11, 2012

Acrylic on deerhide-covered wood panel

22 x 18 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.75. Image courtesy of the artist and Marc Straus LLC, New York and Samson, Boston.

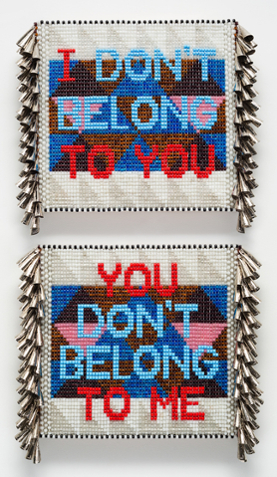

Jeffrey Gibson

(Native American, b. 1972)I Don't Belong To You, You Don't Belong To Me, 2016

Glass beads, tin jingles, artificial sinew, acrylic felt, canvas over wood panel

18 1/4 x 24 x 3 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2017.6.29. Image courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.

An American of Choctaw and Cherokee heritage, Jeffrey Gibson grew up abroad, always experiencing life from outside his culture. Even upon his return to the United States, he struggled to find a place of belonging, as his Native heritage and homosexuality caused him to face feelings of anger over not belonging within mainstream society. I Don’t Belong To You, You Don’t Belong To Me combines the materials and symbols of Gibson’s intersectional communities. As is frequently seen in his work, this diptych is made of glass Crow beads used in powwow regalia. The sides are trimmed with the silver jingles found on ceremonial jingle dresses used in dances that promote healing. Gibson also incorporates words in his art. These are often song lyrics taken from the anthems of gay club culture during the 80s and 90s. This work references George Michaels’ “Freedom! ‘90”, a song about finding one’s path and truth. The artist describes his experience: “What was coming up at the time had everything to do with racism, classism, homophobia, feelings of invisibility, feelings of denial, feelings of inadequacy…and wanting to put that responsibility on somebody outside of myself. But there’s no one singular person. You choose where you’re going to contain these ideas and it becomes a metaphor, and you beat that, and hopefully it’s cathartic on some level. For me it was.”

Jeffrey Gibson

(Native American, b. 1972)Upside Down, 2023

Acrylic on canvas, glass beads, plastic beads, artificial sinew, inset to custom wood frame

74 ¾ x 64 ¾ in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2023.1.25 © Jeffrey Gibson

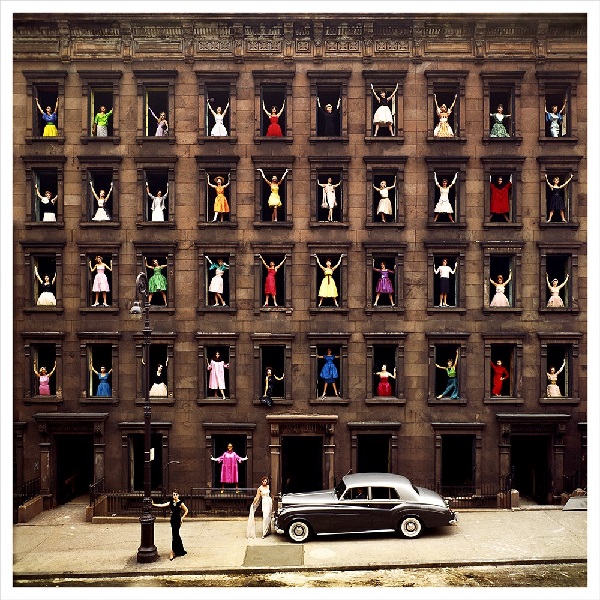

Ormond Gigli

(American, 1925-2019)Girls in the Window, New York, 1960 printed 2021

Archival pigment print

44 x 44 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2021.1.32 © Estate of Ormond Gigli/Courtesy Staley-Wise Gallery, New York

Nyarapayi Giles

(Australian-Ngaanyatjarra, ca. 1940-2019)Warmurrungu, 2016

Acrylic on Canvas

57 1/8 x 57 1/8 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2023.1.16 © Nyarapayi Giles & Tjarlirli Art

Nyarapayi Giles was born in Karrku in the Gibson Desert in Western Australia. She lived a traditional nomadic life in the desert from birth until the 1960s when her family was moved to missions and later settled in the Tjukurla Community in the 1980s. This painting was inspired by Warmurrungu, a ceremonial site near Gile’s place of birth. The painting alludes to one of Giles frequent themes: the site of Warmurrungu where the karlaya, or ancestral emu spirits, are said to dig the ochre deposit to collect the fine powder on their feathers. The red ochre from this region is used in body painting and other rituals and has important ceremonial value. The circular dot work on the canvas traces the movements of the emus across the land, giving visual form to the stories that connect her to the land.

Gauri Gill

(Indian, b. 1970)Untitled (3), 2015-ongoing

Archival pigment print

60 x 40 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2020.1.23 Courtesy Gauri Gill

Gauri Gill

(Indian, b. 1970)Untitled (37), 2015-ongoing

Archival pigment print

42 x 28 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2020.1.22 Courtesy Gauri Gill

Gauri Gill

(Indian, b. 1970)Untitled (48), 2015-ongoing

Archival pigment print

60 x 40 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2020.1.20 Courtesy Gauri Gill

Gauri Gill

(Indian, b. 1970)Untitled (49), 2015-ongoing

Archival pigment print

42 x 28 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2020.1.21 Courtesy Gauri Gill

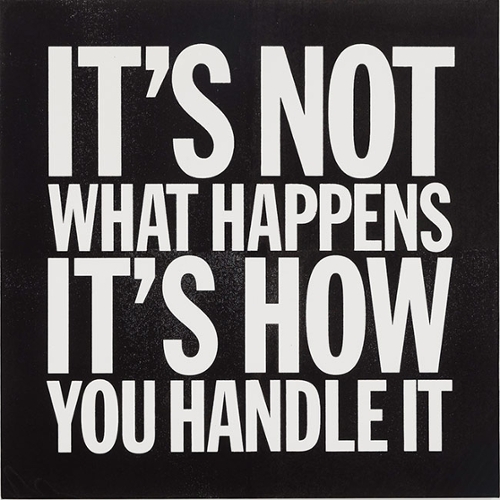

John Giorno

(American, 1936-2019)IT'S NOT WHAT HAPPENS, IT'S HOW YOU HANDLE IT, 2014

Acrylic on canvas

48 x 48 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2015.1.52. Image courtesy of the artist.

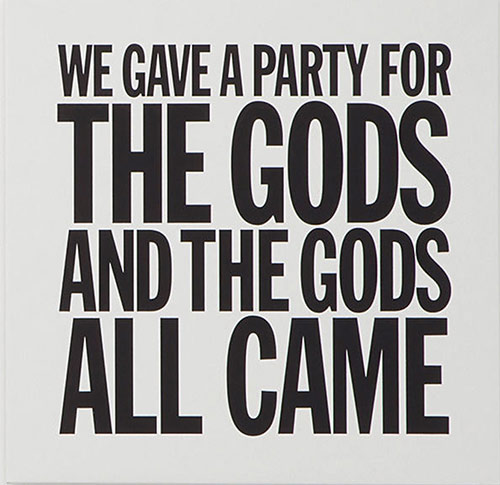

John Giorno

(American, 1936-2019)WE GAVE A PARTY FOR THE GODS AND THE GODS ALL CAME, 2012

Acrylic on canvas

48 x 48 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2015.1.53. Image courtesy of the artist.

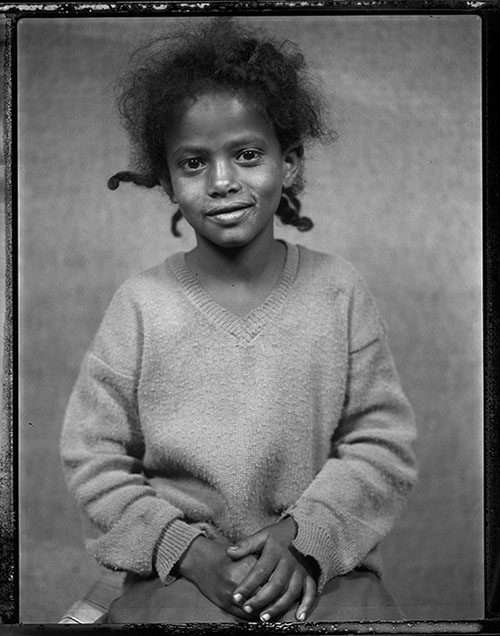

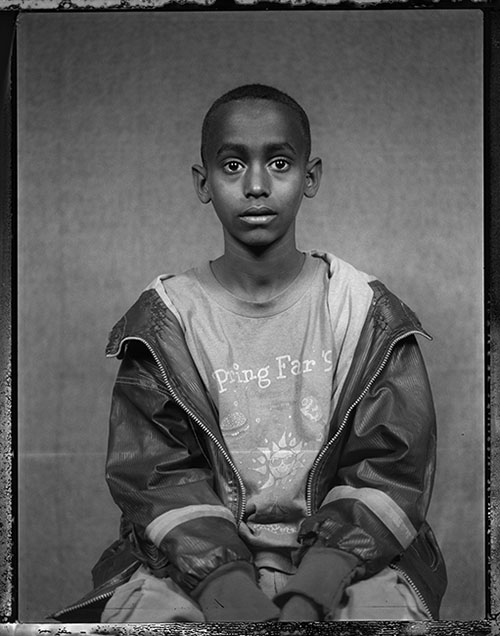

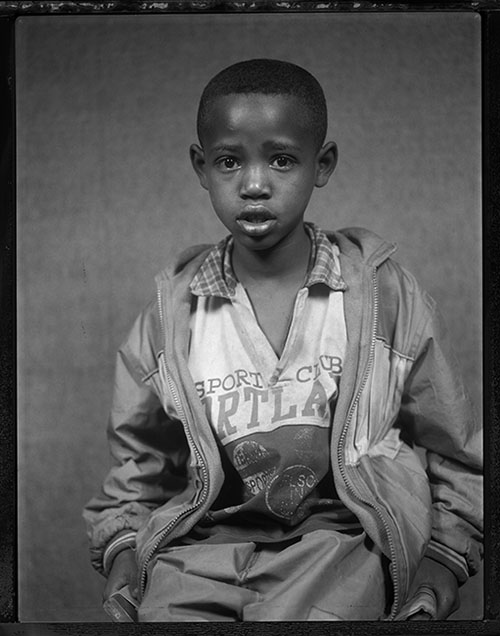

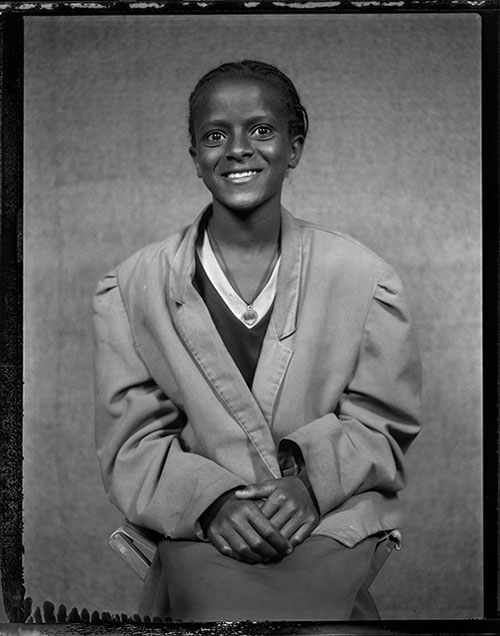

Eric Gottesman

(American, b. 1976)Selected Portrait from a Mobile Studio, Ethiopia, 2004-2012

Selenium toned silver gelatin from Polaroid negatives rear mounted on dibond

14 x 11 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2016.3.10. Image courtesy of the artist.

Artist Eric Gottesman pushes boundaries in his practice, often expanding his physical studio and gallery space to the wider world. While shooting this series of photographs, the artist spent 15 years living in the Shiromeda/Sidist Kilo neighborhood in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. During this time, Gottesman formed strong relationships and engaged members of the community in photographic collaborations, such as this one where he created a “mobile studio” to take portraits of the people in the area. These portraits were then displayed around the neighborhood, exhibiting the various faces and stories of the community. Many of the people depicted in the portraits had never had their photographs taken before, as there were times throughout Ethiopian history when cameras were banned. Therefore, in viewing these works we are granted insight into this special experience for both artist and subject.

Eric Gottesman

(American, b. 1976)Selected Portrait from a Mobile Studio, Ethiopia, 2004-2012

Selenium toned silver gelatin from Polaroid negatives rear mounted on dibond

14 x 11 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2016.3.11. Image courtesy of the artist.

Eric Gottesman

(American, b. 1976)Selected Portrait from a Mobile Studio, Ethiopia, 2004-2012

Selenium toned silver gelatin from Polaroid negatives rear mounted on dibond

14 x 11 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2016.3.12. Image courtesy of the artist.

Eric Gottesman

(American, b. 1976)Selected Portrait from a Mobile Studio, Ethiopia, 2004-2012

Selenium toned silver gelatin from Polaroid negatives rear mounted on dibond

14 x 11 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2016.3.13. Image courtesy of the artist.

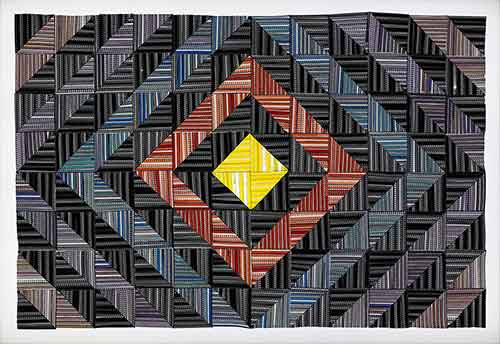

Mary Grigoriadis

(American, b. 1942)Night Bloom, 1983

Oil on Canvas

66 x 69 5/8 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2023.1.19. Image courtesy of the Artist Ave Accola Griefen Fine Art

This painting is part of Mary Grigoriadis’ Portal series, which the artist developed in the 1980s after her father’s death. Through the use of geometric patterns and abstract shapes, the composition suggests the form of a headstone placed at the bottom of the canvas. Grigoriadis’ approach to painting is informed by Greek architecture as well as by Byzantine and Native American elements. In the 1970s, she was a founding member of A.I.R., the first women’s art gallery in the United States, and was also part of the Pattern and Decoration movement. For the artist, composition, pattern, and materiality are key elements of artmaking: “My drawings and paintings depict rigid fantastic structures, densely packed with pattern and color around an open center which functions as an entrance to the space beyond the surface. The work explores the interaction of patterns using a bilaterally symmetrical format of frames within frames. These pieces continue to celebrate opulence, order, and the decorative, without apology.”

Sabrina Gschwandtner

(American, b. 1977)Quilts, Dresses, Arts and Crafts (for Rollins), 2014

16mm film (polyester), polyester thread, lithography ink

53 x 77 3/16 x 6 1/8 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2014.1.33. Image courtesy of LMAK projects and the artist. Photo: Tom Powell Imaging.

Wade Guyton

(American, b. 1972)Untitled, 2021

Epson UltraChrome HDX inkjet on linen

84 x 69 x 1 3/8 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond 2023.1.30. © Wade Guyton