American Art to 1950

The American collection is a core component of the Rollins Museum of Art's mission as a teaching museum. Including oil paintings, sculptures in marble and bronze, drawings, prints, and photographs as well as mixed media works, the collection tells the story of American art from its early portrait-focused days to the heights of modernism. With particular strengths in nineteenth century landscape, the Ashcan School, and printmaking, the American collection is an excellent resource for teachers and students, and also forms a key component of permanent collection exhibitions.

The collection is growing, with recent acquisitions including works by nineteenth and early-twentieth century women artists, early art photography, and American modernism, both abstract and figurative. This growth reflects the evolving needs of the teaching collection, as well as the collecting interests of Rollins alumni, members of the community, and other RMA supporters. A 2019-2022 grant from the Henry Luce Foundation has enabled research and documentation of the collection, with the goal of making it fully available for teaching and research, both digitally and in person.

PLEASE NOTE: Not all works in the Rollins Museum collection are on view at any given time. View our Exhibitions page to see what's on view now. If you have questions about a specific work, please call 407-646-2526 prior to visiting.

Artists Featured in This Section

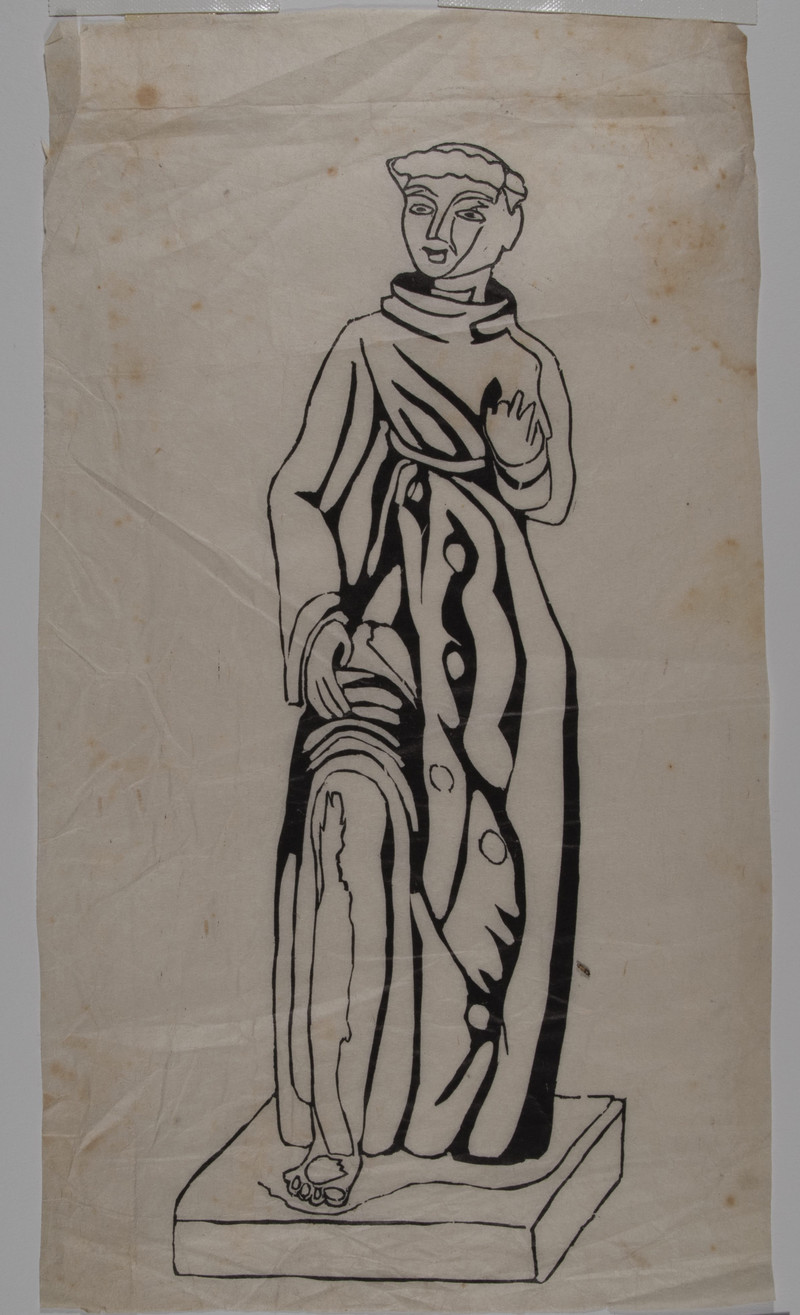

Ivan Albright

(American, 1897-1983)Follow Me, 1948

Lithograph

13 3/4 in. x 8 7/8 in. print

Purchased with the Wally Findlay Acquisitions Fund, 1992.21

Ivan Le Lorraine Albright occupies a unique place in the history of American art. From an artistic family, he at first resisted becoming an artist before realizing that he had both talent for and interest in painting. His paintings, which are usually classified as “magic realist,” frequently depict weighty and macabre themes, including death, aging, and the inevitable decline and decay of the body, which he regarded as a prison for the soul. He worked meticulously and over a period of months or even years, building elaborate sets to stage his haunting compositions. His titles—long and poetic—usually emerged after the paintings were finished, once he truly understood what they were about.

This lithograph was commissioned by Associated American Artists, a gallery which catered to a middle-class audience largely by selling prints made by famous painters. It is based on a similar painting entitled I Walk To and Fro through Civilization and I Talk as I Walk (Follow Me, the Monk) (1926-7, Art Institute of Chicago). It depicts Brother Peter Haberlin, an octogenarian Franciscan friar who was regarded as the last link between the old California missionaries and the modern friars. In the print—as in the painting—the influence of Old Masters, in particular El Greco and Francisco de Zurbarán, is evident in the monk’s flowing, voluminous robes and the flickering quality of the light. Though light streams in through an open window, the monk’s body also glows with an inner light, emphasizing his simple holiness.

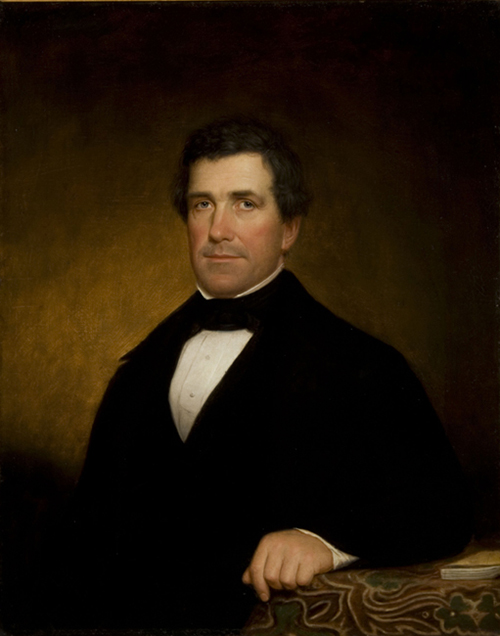

Francis Alexander

(American, 1800-1880)Portrait of Mary Ann Duff, 1825

Oil on canvas

30 1/4 x 24 in.

Gift of Dr. and Mrs. DeWitt Allen Green, 1993.2

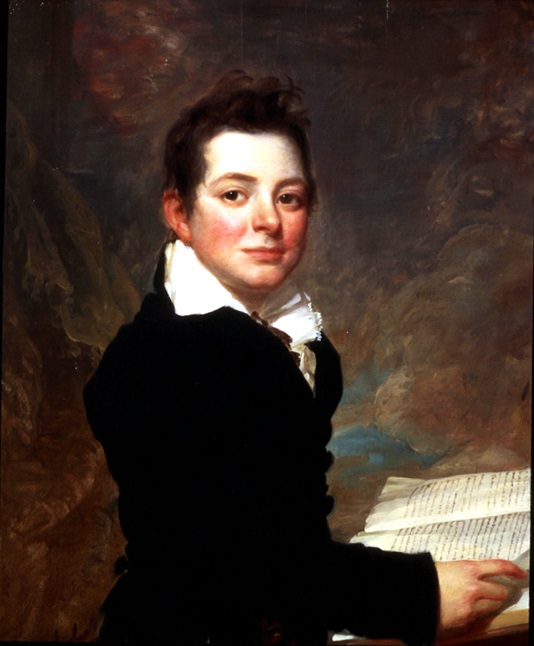

Francis Alexander was twenty-five when he painted Mary Ann Duff. At the peak of her career, Duff was considered as fine a tragic actress as the earlier renowned English actress Sarah Siddons (immortalized as the "Tragic Muse" by Sir Joshua Reynolds in 1783). Though born in England and first appearing on stage as a dancer in Ireland, Duff was thirty and living in New York when this painting was completed. Largely forgotten now, it has been argued that Duff should rightly be considered the first First Lady of the American Stage, having received her theatrical training solely in America. This painting predates Alexander's travels in Europe, where he would study the great monuments of art and refine his technique.

Though produced early in his career in an almost naïf style, Alexander’s likeness captures the vivacious nature of the actress as she looks out of the canvas with sparkling eyes and rosy cheeks. Great care has been taken in rendering the texture and patterning of the drapery that covers her chair and falls over and around her arm. Mary Ann Duff would have been conscious of her rising status on the American stage. A portrait such as this might have been commissioned in a self-conscious attempt at mimicking the habits of respectable American society. Remembering that actors in the nineteenth century were not accorded the high social status in America that they enjoy today, Miss Duff would have been eager to present herself as a reputable lady of society. Her apparel raises more questions than it answers. She appears to be wearing a scholar's cap, and the high, starched, lace collar is not in keeping with contemporaneous fashions. It is possible that she has chosen to be portrayed in the costume of a favorite character. Unfortunately, there is little in the way of records for this important personage of American theatrical history.

John White Alexander

(American, 1856-1915)Portrait of Annie Russell as Lady Vavir in Broken Hearts, ca. 1885

Oil on canvas

72 x 44 1/2 in.

Gift of John Russell Carty (1892–1949), nephew to Annie Russell, 1938.143

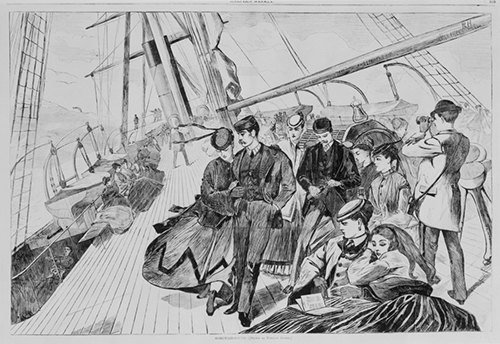

This portrait of Annie Russell, after whom Rollins’ theater is named, dates from early in both her career and in that of the painter, John White Alexander. Alexander, an orphan from Pittsburgh, got his start as an illustrator for Harper’s and other magazines in New York. Like many artists of his generation, Alexander studied in Europe, spending time in Munich and Polling, in Bavaria, as well as Venice. While in Venice he met fellow American James Whistler, who was there to create etchings of the city’s famous architecture and canals. Whistler, one of the foremost proponents of the idea of “art for art’s sake,” would have a profound influence on Alexander, who returned to New York in 1881 and almost immediately established himself as one of the city’s premier portrait painters.

Soon after he executed this work Alexander became well known for his purely aesthetic depictions of women, and this painting is one of his last commissioned portraits. Russell, who is depicted with her back mostly turned to the viewer, is an excellent early example of this tendency in his work. Her long, lean form is contrasted with the smooth roundedness of the vase, and the pink blooms of the flowers seem to reach around her, drawing her in as another of the aesthetic objects in the room. Her costume—from a light fairy comedy by W.S. Gilbert—enhances the effect by taking her out of everyday time and space and into a realm of purest fantasy. Alexander painted at least one other portrait of Russell, and she owned this one throughout her long life.

John Taylor Arms

(American, 1887-1953)Amiens - The Cathedral of Notre Dame, 1926

etching

13 1/2 in. x 13 1/8 in. print

Gift of Lucille Hamiter, 1985.55

Born in Washington, D.C., John Taylor Arms studied architecture at Princeton University, working as an architect in New York City before serving in World War I. After the war he gave up architecture in favor of etching, which he had been practicing as a hobby—his wife, Dorothy, gave him his first etching kit as a Christmas gift. A deeply religious man, Arms was particularly attracted to the Gothic ecclesiastical architecture of Europe, embarking on frequent trips with Dorothy to visit churches and cathedrals in France, Spain, Italy, and England. He typically spent several hours to several days making drawings of each site, which he then translated to etching plates at his home studio.

This print is typical of Arms’s early work, in which he sought to create picturesque views of the vernacular architecture and daily life that had grown up around the churches and cathedrals he depicted. He enjoyed the contrast in uses, scales, and eras that such a framing produced, feeling that it highlighted the enduring power and grandeur of the Gothic buildings. Here the cathedral in Amiens, in Northwest France—built from 1220-1270—towers over the surrounding city, its grandeur highlighted by the almost wispy faintness of the lines Arms uses to depict it. Two peasants are engrossed in conversation in the foreground, suggesting that this exquisite structure is part of everyday life, a fact which Arms found immensely appealing.

John Taylor Arms

(American, 1887-1953)View of Santa Maria Major, Spain, 1935

Drypoint etching

12 in. x 9 in. print

Unknown source, 1957.108

This etching, which depicts the Church of Santa Maria Major in Ronda, Spain, indicates the evolution of Arms’s work after 1927-28. Abandoning the picturesque views incorporating local scenery that had characterized his early work, Arms began instead to depict churches and cathedrals as standalone structures. He believed this allowed the buildings to better stand on their own, reflecting their full majesty and importance. The church, officially dedicated by Ferdinand and Isabella after the culmination of the Reconquista, incorporates Islamic elements, particularly in the minaret tower (leftover from the local mosque) which Arms highlights in this print. The vertical format of the piece emphasizes the tower’s sharp verticality, while the use of negative space effectively evokes the white stucco walls of the relatively unassuming exterior. The sharp, crisp linearity of the scene also evokes the sunny environs of Andalusia, the Southern Spanish province in which Ronda and its church are located.

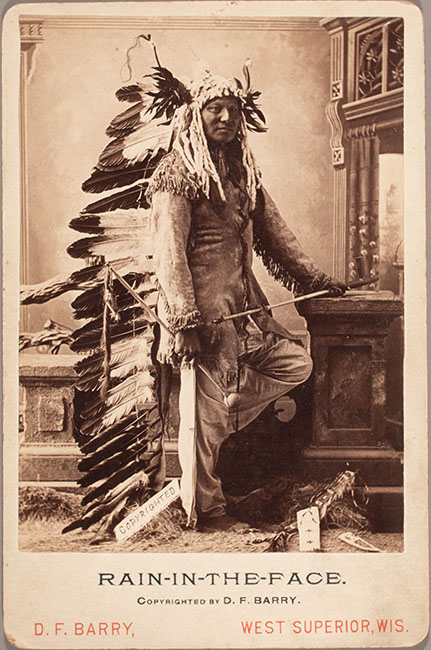

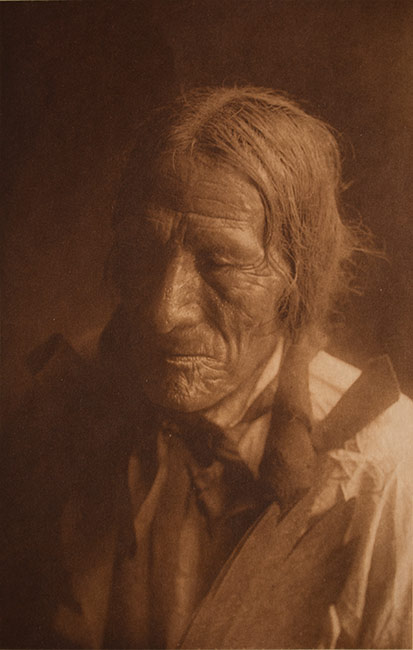

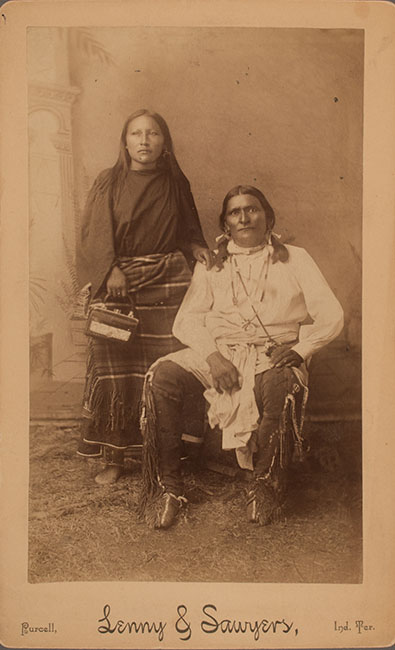

D. F. Barry

(American, 1854-1934)Chief Rain in the Face, Photograph

6 x 4 21/64 in.

The Alfond Collection of Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2017.15.14

D.F. Barry is best known for his portraits of Native American chiefs, warriors, scouts, and women. Often called the “shadow catcher,” Barry captured iconic images of life in the American West. To contemporary viewers from the eastern United States and Europe, his images portrayed a new world they had never seen, allowing his cabinet card photographs to sell in large numbers and quickly. Chief Rain in the Face, the leader of the Lakota Tribe, fought alongside Chief Sitting Bull to defeat Colonel George Custer at the Battle of Little Big Horn. Chief Rain in the Face is photographed in his eagle-feather headdress holding a stone-head club and peace pipe. D.F. Barry’s photos have become iconic symbols of important figures and of what life was like in the Western Frontier. Through his images he has been able to give a glimpse into past moments in time.

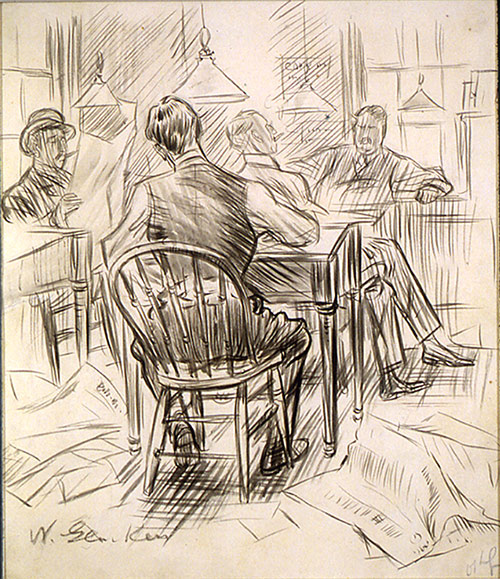

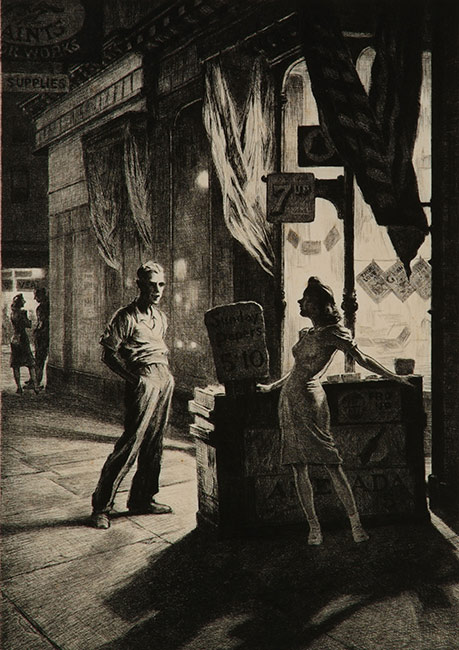

George Wesley Bellows

(American, 1882-1925)Artist's Evening, 1916

Lithograph

8 7/8 in. x 12 1/2 in. print

Purchased by the 15th Anniversary Acquisition Fund 1994.13

The American painter, printmaker, and illustrator George Bellows is best known for his depictions of semi-legal boxing matches and New York City street scenes. Though slightly younger than most of its members, these subjects—as well as his commitment to leftist politics—made him a natural fit with the Ashcan School, the group of painters loosely associated with artist and teacher Robert Henri who depicted everyday life in American cities during the first decades of the twentieth century. Bellows—who died at the age of only 42 after a ruptured appendix—was an innovator in fine art lithography. He worked with master lithographer Bolton Brown to develop a wide range of custom lithographic crayons, which allowed him to achieve much more nuanced atmospheric effects than had previously been achieved in lithography.

This print depicts an evening at Petipas, a popular French restaurant at which the Ashcan artists frequently gathered. The white-bearded standing figure is Irish portrait painter John Butler Yeats (father of poet William Butler Yeats). He speaks with mustachioed Robert Henri, while the balding Bellows leans in behind them. The seated, stylishly dressed woman is Bellows’s wife Emma. She gazes confidently out at the viewer, drawing them into the warm, collegial scene. It is striking that Bellows included her front and center in this view of his intellectual and artistic world, indicating her centrality to his creative process.

Frank Weston Benson

(American, 1872-1951)Lily Pond, 1923

Oil on Canvas

44 x 36 in.

Intended Gift from the Martin Andersen – Gracia Andersen Foundation, Inc. 2022.13.LTL

Born in Salem, Massachusetts, Frank Weston Benson spent the majority of his life in and around Boston. He studied at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and—along with his classmate Edmund Tarbell—was a long-tenured and popular teacher and administrator at the school. Along with fellow painters including Tarbell, John Henry Twachtman, and Childe Hassam, Benson was a founding member of The Ten, a group of American painters—many of whom were influenced by French Impressionism—who rebelled against the conservatism of the American art establishment of the late nineteenth century. Despite this antiestablishment affiliation—or perhaps because of it—Benson remained a beloved teacher at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts until his retirement in 1913.

Though Benson is best remembered as an artist of sporting scenes, he was also an accomplished and widely respected landscape painter. This painting was made at Wooster Farm, his family’s property on North Haven Island, the same location where he created many of his most iconic sporting pictures. It depicts a pond Benson had dug for his wife, Ellen, who planted it with waterlilies. In 1921, shortly before completing this work, Benson—who was in search of a new way to depict outdoor scenes—had begun experimenting with watercolors, becoming quite prolific in the medium. His experimentation also impacted his oil paintings, as he developed a looser and more aqueous application of paint. That influence is evident here in the free, even smeary quality of the paint. His adoption of the waterlily, one of the most quintessentially Impressionist subjects, shows his continuing engagement with the style, which he had adopted seriously after joining the Ten American Painters in 1898.

Frank Weston Benson

(American, 1862-1951)Log Driver, 1924

Etching

9 7/8 in. x 12 in. print

Miss Elizabeth Brothers, 1985.51

Born in Salem, Massachusetts, Frank Weston Benson spent the majority of his life in and around Boston. He studied at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and—along with his classmate Edmund Tarbell—was a long-tenured and popular teacher and administrator at the school. Along with fellow painters including Tarbell, John Henry Twachtman, and Childe Hassam, Benson was a founding member of The Ten, a group of American painters—many of whom were influenced by French Impressionism—who rebelled against the conservatism of the American art establishment of the late nineteenth century.

Benson was best known as a painter, but he was also an accomplished and prolific etcher, picking up the medium only in 1912, long after he had made his name as a painter. This image, depicts a working man moving a recently harvested log downriver for processing. Benson frequently traveled along the coast and in the interior of Maine, where he likely made the drawing that inspired this image. Its spare use of line and correspondingly large amounts of negative space reflect the influence of James Whistler, while the workaday subject and fresh, almost sketchy immediacy are reminiscent of Impressionism.

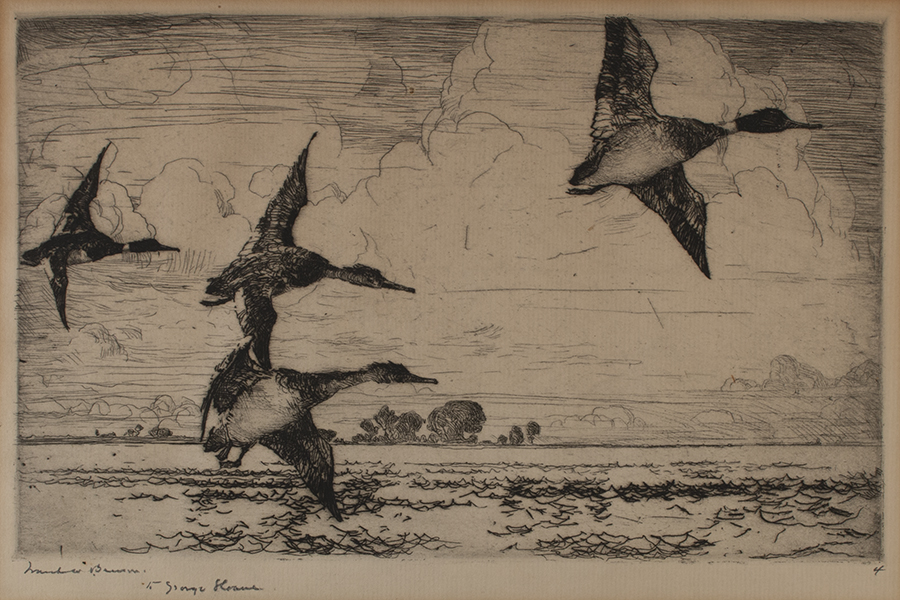

Frank Weston Benson

(American, 1862-1951)Geese Drifting Down, 1929

Etching print

Gift of F. Anthony Capodilupo and Sandra M. Sommer, 2016.35

Benson was an avid sportsman who was first inspired to paint at the age of sixteen after shooting a snipe and a rail in the salt marshes near his Essex County, Massachusetts home. Early in his career, he used the prize money from an exhibition to finance the purchase—along with two of his brothers-in-law—of a small hunting cabin in Eastham, on Cape Cod. Later, he would frequently travel to the island of North Haven in Maine’s Penobscot Bay, where he found the inspiration for most of his outdoor scenes. It was at his farmstead there that he took up etching in 1912—he had experimented with it in his student days but left it behind as he established his career as a painter. This inaugurated a remarkable second career as perhaps America’s foremost producer of bird prints, helping to establish it as a standalone genre.

Though he had been inspired by the ornithological illustrations of John James Audubon early in his life—aspiring to a career as an illustrator as a teenager—Benson’s etchings are very different from Audubon’s highly detailed and rigidly posed illustrations. Befitting his interest in Impressionism, Benson prefers to represent his birds in motion, especially in flight. Rather than aiming for anatomical precision, he emphasizes the evanescent qualities of light and air, as well as the light liveliness of the birds themselves. As in Log Driver, Benson demonstrates in this and his other wildlife prints a mastery of negative space, using expanses of white to represent the calm placidity of the New England water, which stands in marked contrast to the bold dynamism of the geese.

Frank Weston Benson

(American, 1862-1951)Springing Teal, Etching

Gift of F. Anthony Capodilupo and Sandra M. Sommer, 2016.36

Frank Weston Benson

(American, 1862-1951)Shoveler Drake, Etching

11 x 8 1/2 inches framed

Gift of F. Anthony Capodilupo and Sandra M. Sommer, 2016.37

Frank Weston Benson

(American, 1862-1951)November Moon, Gift of F. Anthony Capodilupo and Sandra M. Sommer, 2016.38

Frank Weston Benson

(American, 1862-1951)Pair of Pintails, Etching

Gift of F. Anthony Capodilupo and Sandra M. Sommer, 2016.39

Frank Weston Benson

(American, 1862-1951)Wild Geese, Etching

Gift of F. Anthony Capodilupo and Sandra M. Sommer, 2016.40

Frank Weston Benson

(American, 1862-1951)Canvasbacks, Etching

Gift of F. Anthony Capodilupo and Sandra M. Sommer, 2016.41

Frank Weston Benson

(American, 1862-1951)Flying Widgeon, Etching

Gift of F. Anthony Capodilupo and Sandra M. Sommer, 2016.42

Frank Weston Benson

(American, 1862-1951)Redheads No. 2, Etching

Gift of F. Anthony Capodilupo and Sandra M. Sommer, 2016.43

Frank Weston Benson

(American, 1862-1951)Sheldrake, Etching

Gift of F. Anthony Capodilupo and Sandra M. Sommer, 2016.44

Frank Weston Benson

(American, 1862-1951)Evening, Etching

Gift of F. Anthony Capodilupo and Sandra M. Sommer, 2016.45

Frank Weston Benson

(American, 1862-1951)Flying Widgeon, Etching

Gift of F. Anthony Capodilupo and Sandra M. Sommer, 2016.46

Frank Weston Benson

(American, 1862-1951)The Visitor, Etching

Gift of F. Anthony Capodilupo and Sandra M. Sommer, 2016.47

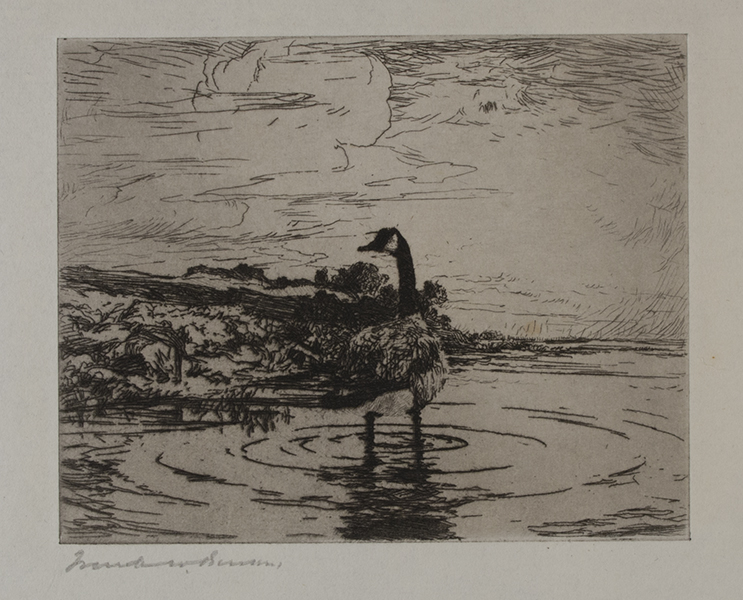

Frank Weston Benson

(American, 1862-1951)Canada Goose, Etching

Gift of F. Anthony Capodilupo and Sandra M. Sommer, 2016.48

Frank Weston Benson

(American, 1862-1951)Flying Pintail, Etching

Gift of F. Anthony Capodilupo and Sandra M. Sommer, 2016.49

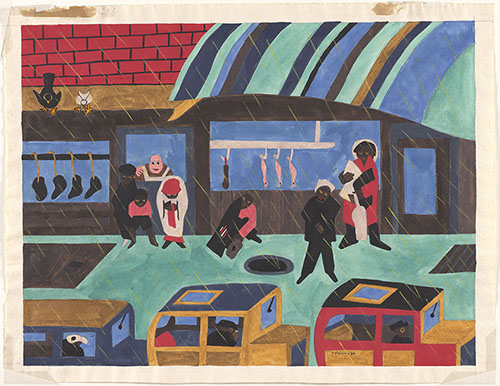

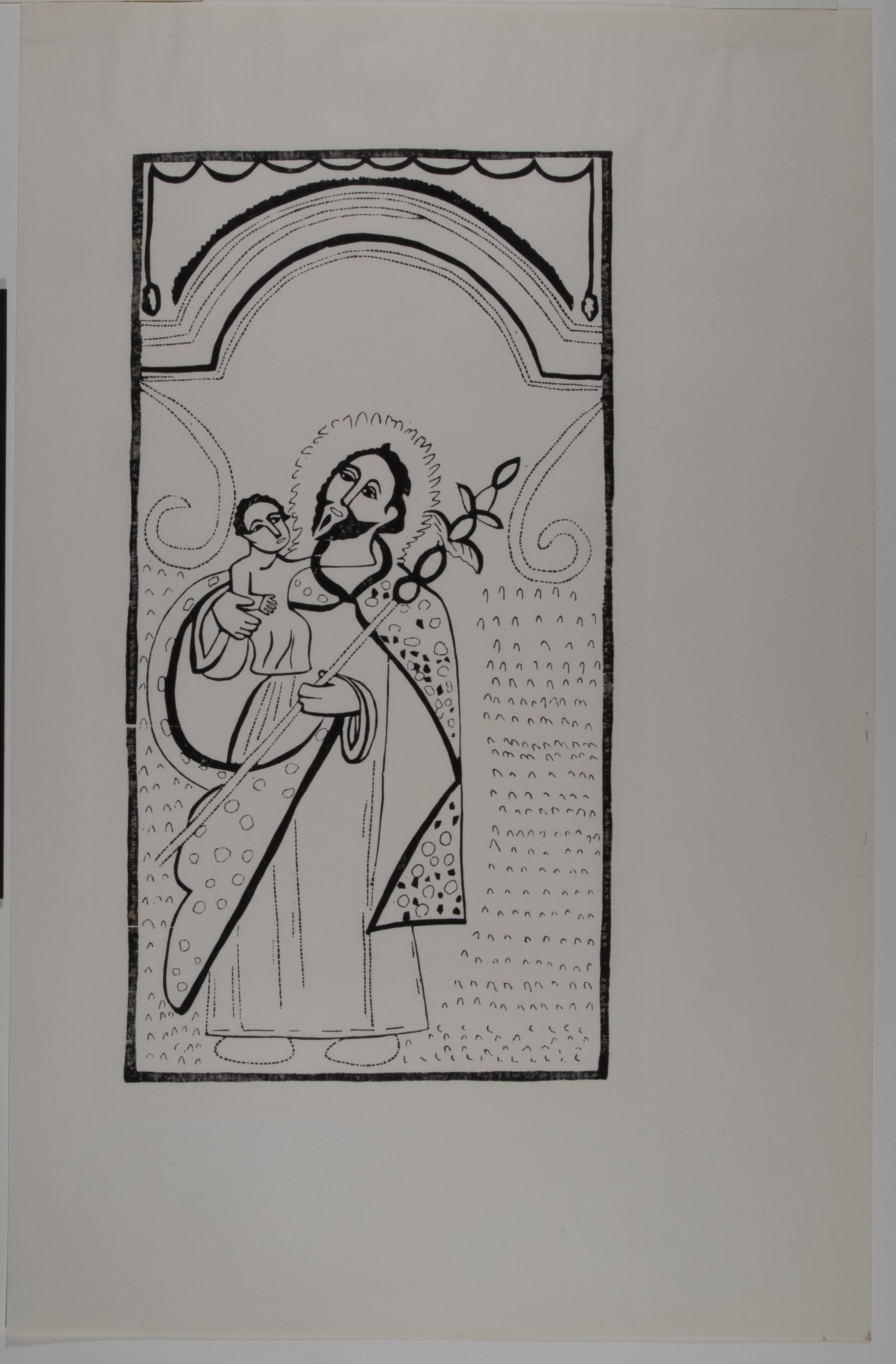

Thomas Hart Benton

(American, 1889-1975)Aaron, 1941

lithograph on wove paper

12 7/8 in. x 9 1/2 in. print

Purchased by the Friends and Partners of the Cornell Acquisitions Fund, 1993.5 © Thomas Hart Benton/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Thomas Hart Benton, along with John Steuart Curry and Grant Wood, was a foremost artist of the Regionalist movement in the United States. Championing a figurative style indebted to earlier twentieth century modernism and the public art of the Mexican muralist movement, Benton was a loud, even combative, voice for the depiction of distinctively American subjects in a distinctively American style. A longtime resident of New York, he famously left it in 1935 to return to his native Missouri, where he had been commissioned to paint A Social History of Missouri, a series of murals in the state capitol in Jefferson City. Benton taught at the Kansas City Art Institute from 1935 to 1941, when he was fired for criticizing the closely affiliated Nelson-Atkins Art Museum.

This print is based on a painting of the same name (1941, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts) which was made as a classroom demonstration during his last year as a teacher. It depicts Ben Nichols, an eighty-two-year-old former slave who Benton has transformed into the Biblical figure Aaron, older brother of Moses. Aaron’s lined face and downcast eyes transmit a solemn dignity, while the busy mustache and crinkle of the mouth convey the sitter’s individual personality. This print was issued in edition of 250 by the Associated American Artists, a company which sold fine art prints by noted American artists for the low price of five dollars, thereby greatly expanding the audiences of artists like Benton, who was an early champion of the company.

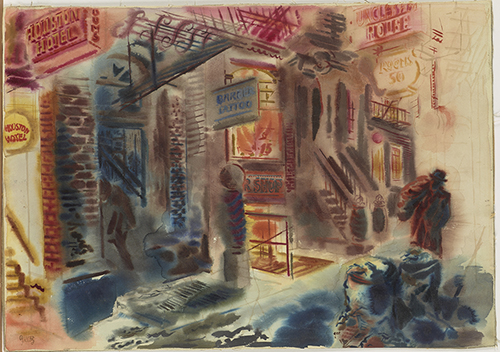

Eugene Berman

(American, b. Saint Petersburg, Russia, 1899-1972)Italienne Symphony II, 1940

Watercolor and ink

10 7/8 in. x 14 3/4 in. painting

Purchased by the Wally Findlay Acquisitions Fund, 1993.7

Born in Russia, Eugene Berman fled the Russian Revolution with his brother Leonid (also a painter), emigrating to Paris in 1918. There he formed the core of the Neo-Romantic movement along with fellow Russian Pavel Tchelitchev and Frenchman Christian Bérard. Berman gained particular renown as a set designer for ballets and operas, where he was known for taking liberties with historical settings in favor of his preferred aesthetic, which emphasized the stark grandeur and mysterious light of ancient ruins, as well as a preoccupation with the macabre. He moved to New York in 1935, becoming one of the most important designers for the opera and theater there, including doing work for the New Ballets Russes under Colonel Wassily de Basil and the Metropolitan Opera under Rudolf Bing.

This watercolor and ink drawing is a conceptual sketch for a proposed staging of Felix Mendelssohn’s Symphony No. 4 in A major, commonly called the Italian, which was to be produced by de Basil and choreographed by the dancer and choreographer David Lichine. The ballet was never staged, but the drawing remains as a fine example of Berman’s creative process, demonstrating how he would have translated the symphony. The blotchy smears of the watercolor help to unify the grand proscenium of the stage with the set design, which includes a tilting, ruined flag and moldering ruins. The symphony itself is considerably more lively than Berman’s rendering suggests, indicating the influence his Neo-Romantic sensibilities had on his set designs.

Albert Bierstadt

(American, 1830-1902)Shoshone Indians Rocky Mountains, 1859

Oil and gouache on paper mounted on board

5 x 7 5/16 in.

Gift of Samuel B. and Marion W. Lawrence, 1991.9

Albert Bierstadt, who is best known for his monumental depictions of American scenery, was, like many artists of his generation, trained abroad. When he arrived in Düsseldorf, Germany in 1853 to study at the famed Kunstakademie there, his fellow Americans Worthington Whittredge and Emanuel Leutze were so unimpressed with his talent that they doubted he would make it as an artist. Undeterred, Bierstadt disappeared for a summer of sketching along the Rhine River and in the Hartz Mountains. Upon his return to Düsseldorf, Bierstadt’s improvement was apparently so marked that Whittredge, Leutze, and several other artists were compelled to send a letter to a newspaper in Bierstadt’s hometown of New Bedford, MA, swearing that the works the painter was sending back were his own, and not those of Andreas Achenbach or another German artist.

After a few years in Düsseldorf and traveling throughout Europe, in particular the Alps, Bierstadt returned to the United States with a plan. Securing a position on the surveying expedition commanded by Colonel Frederick W. Lander, Bierstadt turned the fine eye for detail he had honed in Germany on the scenery of Nebraska and Wyoming. He sent a voluminous correspondence detailing his adventures to eager readers back East, ensuring that there would be a strong market for his work upon his return. Though he is best known for his highly finished large-scale compositions, this and similar sketches reveal his sensitivity to effects of light and atmosphere, and his ability to capture people and animals, as well as forbidding mountain peaks. Bierstadt used sketches like these, photographs, and American Indian artifacts and other materials he gathered on this and subsequent expeditions—all of which he kept and displayed in his studio in the famed Tenth Street Studio Building—as part of a very successful marketing strategy that resulted in his becoming the wealthiest artist in the United States by the late 1860s.

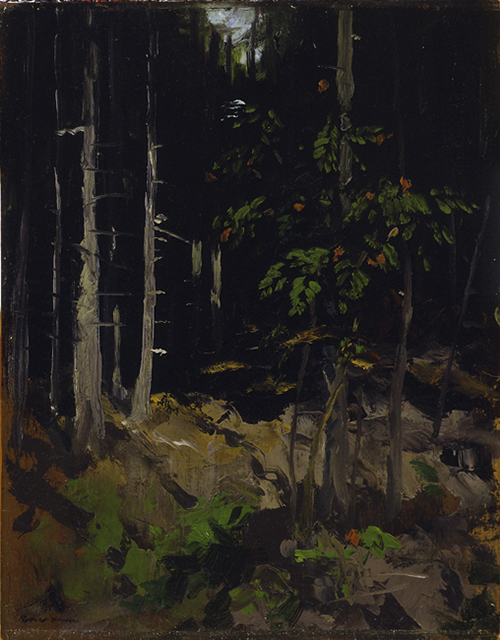

Ralph Albert Blakelock

(American, 1847-1919)Rising Moon, 19th century

Oil on Canvas

24 3/8 x 29 5/8 in.

Gift from the Winnifred Johnson Clive Foundation 2023.33

The son of a successful physician, Ralph Albert Blakelock was originally supposed to follow his father into medicine. After a few semesters of medical college, however, he felt the stronger pull of an artistic career and dropped out. Largely self-taught, he quickly mastered the basics of Hudson River School landscape. From the beginning, however, he felt a lack of affinity with the sunny, optimistic style, preferring to paint in a more personal, romantic manner. Early in his career this placed him outside the artistic mainstream, and he struggled to support his large family on the sales of his paintings. This struggle was exacerbated by his battles with mental health, as he increasingly began to suffer from both depression and delusions of grandeur, eventually landing him in a psychiatric hospital in 1899; he spent most of the final twenty years of his life institutionalized.

Though his mental health struggles—as well as his many paintings of dark and mysterious moonlit scenes—have often led to Blakelock’s being termed an outsider or visionary, he actually was closely integrated into the New York art scene of his day and kept current with artistic trends both in the United States and abroad. His painting was heavily influenced by the French Barbizon school, from which he gained an appreciation for romantic subjectivity and the loose handling of paint. Rising Moon is an example of his most well-known style of painting, in which entirely imagined landscapes—rather than real places—are presided over by large, luminous moons. The painting reverses the usual landscape elements, with inky dark foreground trees and other elements giving way to more luminous water and sky in the background. As Blakelock languished in mental hospitals, often struggling to gain access to basic painting supplies, appreciation for his unique vision grew in the wider world. A painting similar to this one sold for $20,000 in 1916, a record for a living American painter at the time.

Robert Frederick Blum

(American, 1857-1903)Flora de Stephano, 1896

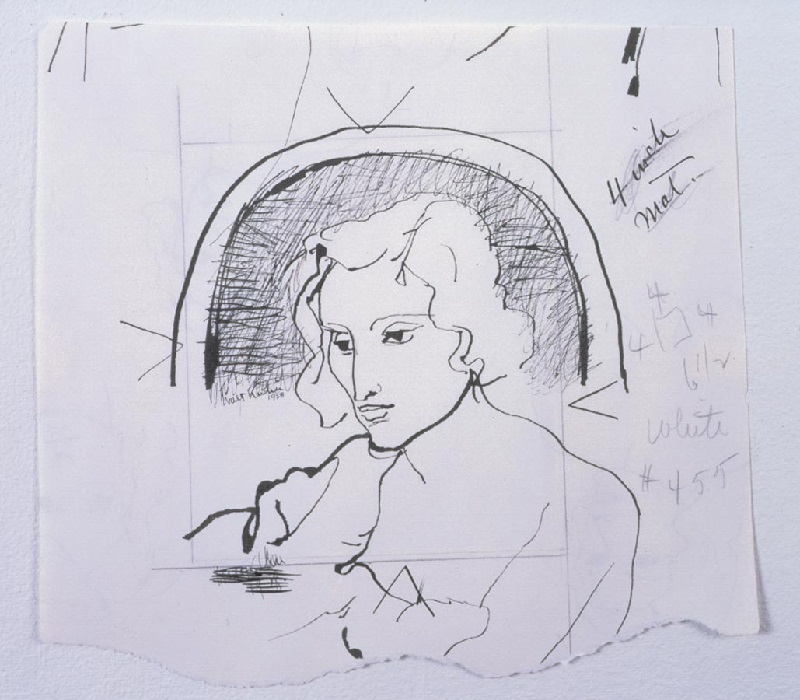

Pencil

10 7/8 in. x 8 7/8 in.

Purchased by the Dr. Kenneth Curry Acquisition Fund, 2001.3

Growing up in Cincinnati, Robert Frederick Blum was heavily influenced by the work of Spanish painter Mariano Fortuny, which he saw in local collections. He adopted the older painter’s use of a rapid, sketchy line to quickly delineate the forms of his sitters’ faces, relying on variations in line weight and tone to suggest contours. In his late teens Blum moved to Philadelphia to study at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts before moving on to New York, where he established himself as a professional illustrator and fine artist. Always a slow worker in oils, Blum preferred the sketchy immediacy of drawing and etching, a medium he picked up after meeting James Whistler—the acknowledged master of the medium—in Venice.

From Whistler he also picked up another technique, the “Japanese method” of drawing. Taken from Whistler’s study of Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints, it involved starting from the point he expected to be the exact center of focus in the work and proceeding outward, a process which in this case results in the model’s prominent nose and striking eyes dominating the composition. Little is known about De Stephano, who appears to have been Blum’s lifelong friend and sometime companion. Though Blum never married, she claimed to be his widow after his premature death in 1903. She served as his model for a number of aesthetic portraits, as well as the murals Moods to Music and The Vintage Festival, originally executed for New York’s Mendelssohn Hall and now at the Brooklyn Museum.

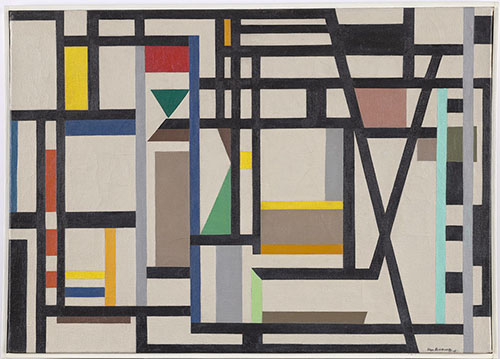

Ilya Bolotowsky

(American, b. Saint Petersburg, Russia, 1907-1981)Abstraction, 1947

Oil on Linen

18 x 25 1/2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2017.15.1 © Estate of Ilya Bolotowsky/Licensed by VAGA, New York

Ilya Bolotowsky stood at the forefront of abstraction in the United States during a time when many in the American art world were reluctant to embrace non-objective art. After immigrating to the United States as a teenager Bolotowsky studied at the conservative National Academy of Design and worked as a textile designer. After a trip to study art in Europe he happened to encounter the work of Piet Mondrian and Joan Miró, and his early work attempted to blend Mondrian’s geometric style with Miró’s biomorphic abstractions. In 1936 he became a co-founder and president of American Abstract Artists, a group of painters and sculptors who were frustrated by their exclusion from the major modern art venues in New York, including the Museum of Modern art and the Whitney Museum of American Art.

In 1945, after serving in the military during World War II, Bolotowsky refocused his artistic attention on Mondrian, who had spent the last years of his life in New York, where he had been hugely influential on the art world there. This work reflects the influence of the gridded, non-spatial canvases of Mondrian’s Neoplasticism, though in this piece Bolotowsky retains non-primary colors and diagonal lines, elements which Mondrian had abandoned later in his career. This work was made while Bolotowsky was serving as a replacement for Josef Albers, who was on sabbatical from Black Mountain College. For the remaining decades of his life Bolotowsky would be a well-regarded art teacher at a series of colleges and a strenuous advocate for geometric abstraction.

Henry Botkin

(American, 1896-1983)Solo (Trumpet Player), 1948

Oil on Canvas

21 x 14 inches

Bequest of Dr. Kenneth Curry, Ph.D. ’32, 2000.1.6

Henry Botkin was born in Boston, Massachusetts, attending various art schools there from 1913 to 1917. In 1917 he moved to New York, where he studied at the Art Students’ League. While studying he lived with his famous cousins, the composer George Gershwin and his lyricist brother Ira. In 1926 Botkin moved to Paris, where he continued to study art while also acting as Gershwin’s art agent, sending the composer (an enthusiastic collector) photos and prices of paintings he might like to acquire. Gershwin liked the works of the Fauves and other slightly earlier Modernist painters, commenting in letters to his cousin on their use of color and form. When Botkin returned to New York in 1933 he taught Gershwin to paint and draw, and also accompanied him on the 1934 trip to Folly Island, South Carolina which would result in Porgy and Bess, perhaps Gershwin’s most famous work. As Gershwin was writing his jazz opera Botkin was at work on a series of paintings depicting similar people and themes.

This painting, executed in the middle of Botkin’s long life, shows both the artist’s engagement with the figurative painting traditions of the first half of the twentieth century and the influence of his musician cousins. The titular trumpeter, rendered in a series of Cubist-derived flat planes, sits contemplatively on a broad low stool, while the musical notes of his profession float in the flattened space around him. The generally cool, bluish cast of the figure stands in stark contrast to the reds and oranges of the surrounding space, suggesting both the intellectual and sensuous aspects of musical performance.

Margaret Bourke-White

(American, 1904–1971)Village School Kolomna: Volga Region, early 1930's

Photogravure print

16 x 20 in. (40.64 x 50.8 cm) photograph

Museum purchase from the Michel Roux Acquisition Fund, 2013.15 © 2023 Estate of Margaret Bourke-White / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Margaret Bourke-White first travelled to the Soviet Union in the summer of 1930, the first of three consecutive summers when she documented the first Soviet five-year plan for American audiences, the first Western photographer to do so. Bourke-White made her fame in the 1920s as an industrial photographer, pioneering a technique to capture the stark beauty of the Otis Steel Company in Cleveland, among other icons of American heavy industry. That resulted in her being hired by Henry Luce to work at Fortune magazine, which sent her on the assignment to the USSR.

During her first trip, Bourke-White focused on the heavy machinery in mines and factories, but found herself increasingly interested in the people she met on her journey, finding herself charmed by their solid resilience. This photo depicts students in a small village school outside the city of Kolomna, southeast of Moscow, reflecting that interest in the Russian people. Bourke-White has arranged her thirteen sitters in a rough pyramid that emphasizes their solidity, as do the rough-hewn but sturdy pews and walls of their surroundings. Bourke-White’s increasing empathy for the Soviet people prompted a similar identification with working-class people in the United States, and her Popular Front sympathies earned her the attention of J. Edgard Hoover and the House Un-American Activities Committee.

Margaret Bourke-White

(American, 1904–1971)Ekaterina Dzhugashvili: Mother of Joseph Stalin, 1931

Photogravure print

20 x 16 in. (50.8 x 40.64 cm) photograph

Museum purchase from the Michel Roux Acquisition Fund, 2013.16 © 2023 Estate of Margaret Bourke-White / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

During a return trip to the Soviet Union Bourke-White rode through the Caucuses on horseback, accompanied by seven Soviet commissars, often sleeping in caves and eating sheep that local villagers had roasted whole. Hearing that Josef Stalin’s birthplace was nearby she went to photograph it, finding the leader’s earthen-floored house and a great-aunt. She then went to Tiflis, the Georgian capital, and photographed Stalin’s mother, who she reported did not fully understand her son’s job, and would have preferred he had joined the priesthood. The close-cropped portrait emphasizes the woman’s traditional dress and severe expression, as well as her eyes, which are enlarged by the effect of her eyeglasses.

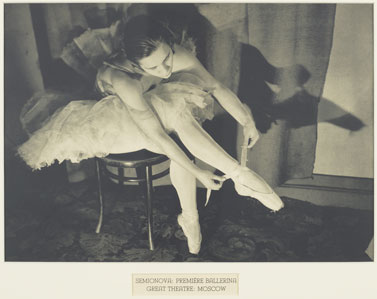

Margaret Bourke-White

(American, 1904–1971)Semionova: Premiére Ballerina Great Theatre: Moscow, 1931

Photogravure print

16 x 20 in. (40.64 x 50.8 cm) photograph

Museum purchase from the Michel Roux Acquisition Fund, 2013.17 © 2023 Estate of Margaret Bourke-White / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Margaret Bourke-White

(American, 1904–1971)The Steppe: Ukraine, 1934

Photogravure print

16 x 20 in. (40.64 x 50.8 cm) photograph

Museum purchase from the Michel Roux Acquisition Fund, 2013.18 © 2023 Estate of Margaret Bourke-White / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Margaret Bourke-White

(American, 1904–1971)A Priest, 1931

Photogravure print

20 1/4 in. x 16 1/4 in. photograph

Museum purchase from the Michel Roux Acquisition Fund, 2013.19 © 2023 Estate of Margaret Bourke-White / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Margaret Bourke-White

(American, 1904–1971)At the Circus, 1931

Photogravure Print

16 ¼ x 20 ¼ in.

Museum purchase from the Michel Roux Acquisition Fund, 2013.20 © 2023 Estate of Margaret Bourke-White / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Margaret Bourke-White

(American, 1904–1971)Bolshevic Babies in the Nursery: AMO Automobil Factory, 1931

Photogravure print

16 1/4 in. x 20 1/4 in.

Museum purchase from the Michel Roux Acquisition Fund, 2013.21 © 2023 Estate of Margaret Bourke-White / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

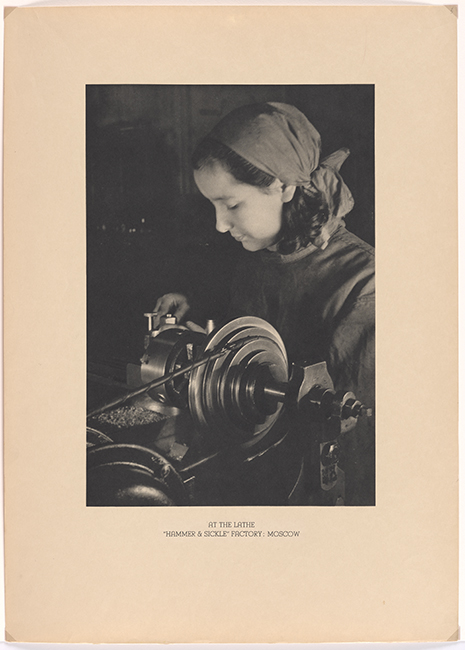

Margaret Bourke-White

(American, 1904-1971)At the Lathe "Hammer & Sickle" Factory: Moscow, 1931

Photogravure print

20 ¼ x 16 ¼ in.

Museum purchase from the Michel Roux Acquisition Fund, 2013.22 © 2023 Estate of Margaret Bourke-White / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

In her 1931 book Eyes on Russia and subsequent articles for the New York Times Magazine, Bourke-White wrote of her experiences traveling on overwhelmed Soviet trains to visit factories and other industrial sites, often subsisting on little more than cold canned beans she had brought with her from Germany. She also wrote a great deal about Soviet women, on whose labor the five-year plan relied just as much as that of men. Attempting to reconcile this with American notions of feminine comportment, she commented that the Russian woman, “In her longing for fashionable clothes, for adornment, for attention…is wholly feminine.,” while, at the same time “…working, as the men work, to advance the great industrial program of which she feels she is part. She is never conscious of a conflict between her career and her personal life.”

Margaret Bourke-White

(American, 1904–1971)Soviet Serenade, 1931

Photogravure Print

20 x 16 in.

Museum purchase from the Michel Roux Acquisition Fund, 2013.23 © 2023 Estate of Margaret Bourke-White / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Margaret Bourke-White’s modern aesthetic and attention to the concerns of the machine age inspired Henry Luce to hire her as a photographer at Fortune magazine. While on assignment for the magazine, she made three trips to the USSR. In 1930, she visited eastern Ukraine and southern Russia

and photographed the construction of the Dnieper Hydroelectric Station (DniproHES), the Stalingrad Tractor Factory, and the Novorossiysk Cement Plant, and in 1931 she traveled to Chelyabinsk Oblast to cover workers building the largest steel mill in the world, the Magnitogorsk Iron and Steel Works (MMK). In the summer of 1932, she returned to the USSR, traveling from the Caucasus to Baku and back

to Ukraine, where she found herself increasingly interested in the strength and character of the Soviet people. Soviet Serenade (1931) captures a street performer smiling as he plays his accordion and looks down upon the viewer.

Margaret Bourke-White

(American, 1904–1971)Kremlin: Moscow, 1931

Photogravure Print

16 x 20 in.

Museum purchase from the Michel Roux Acquisition Fund, 2013.24 © 2023 Estate of Margaret Bourke-White / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Margaret Bourke-White

(American, 1904–1971)For the Iron Mine Foundations: Magnet Mountain, 1931

Photogravure Print

16 x 20 in.

Museum purchase from the Michel Roux Acquisition Fund, 2013.25 © 2023 Estate of Margaret Bourke-White / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Margaret Bourke-White

(American, 1904–1971)Borscht (detail), 1931

Photogravure print

16 x 20 in.

Museum purchase from the Michel Roux Acquisition Fund, 2014.8 © 2023 Estate of Margaret Bourke-White / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

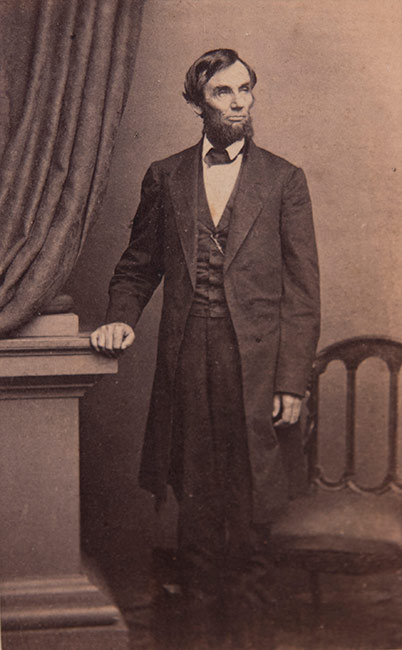

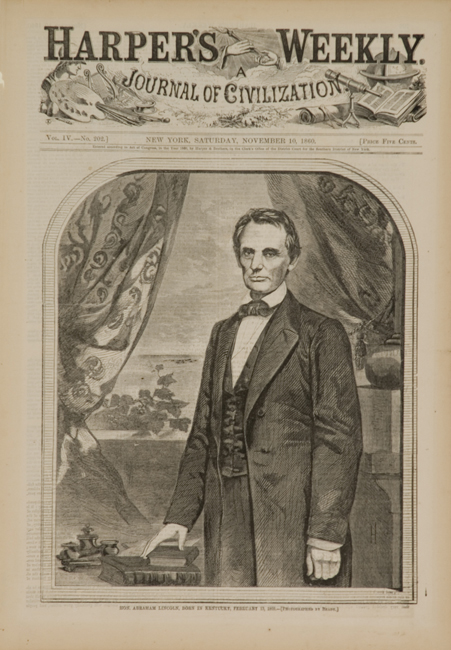

Mathew M. Brady

(American, 1823–1896)Abraham Lincoln, 1861

Albumen print from wet collodion negative

Purchased with the Michel Roux Acquisitions Fund, 2013.9

Mathew Brady was already the most famous photographer in America by 1860, when his studio took its first image of Abraham Lincoln, commemorating the Republican presidential candidate’s February 27, 1860 speech at Cooper Union in New York City. Lincoln credited that image—reproduced on the cover of the printed speech as well as disseminated widely as a carte de visite—with helping him earn the nomination and eventually the presidency. It also began a long-running collaboration between America’s foremost photographer and its most famous politician, with Lincoln posing for photographs at Brady’s studio throughout the Civil War. Lincoln’s images on both the five-dollar bill and penny are based on such photographs, as are most of the familiar images of the sixteenth president.

The carte de visite format was revolutionary, for it allowed an unlimited number of inexpensive paper prints to be made from one glass-plate negative, permitting the photograph to be distributed widely, in contrast to the daguerreotype and ambrotype, earlier formats in which only a single image was made. Americans of all walks of life amassed large collections of images of famous people, making this the first time in history when the faces of the country’s leaders were widely known. This image was captured by Thomas Le Mere, a photographer who worked at Brady’s Washington, D.C. studio. This captures an important aspect of Brady’s work, which is the fact that he rarely took or developed the images himself, though he usually posed particularly important clients. This was standard practice at the time, in contrast with the twentieth century, when photographers came to be seen as individual artists who controlled the entire process. During the war Brady’s photographers spread out to follow the Union Army on its campaigns, bringing Americans some of the first photographic images of war and inaugurating a tradition of photojournalism that survives to this day.

Jennie Augusta Brownscombe

(American, 1850-1936)The Choir Boys, ca.1895

Oil on Canvas

36 in. x 24 in. painting

Gift of Mr. And Mrs. William Curtiss, 1957.19

Born near Honesdale, in rural northeastern Pennsylvania, Jennie Brownscombe belonged to the first generation of American women artists for whom professional training was routine, if still often segregated from men. After a stint as a schoolteacher in her late teens she moved to New York, where she enrolled at The Cooper Union, graduating in 1871. She then studied at the National Academy of Design, becoming a founding member of the Art Students League in 1875. She first attracted notice in 1876, exhibiting her work in the Women’s Pavilion at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. Throughout the remainder of her long life she maintained a successful career as a portraitist and painter of genre scenes, both historical and contemporary. Many of her works were reproduced as prints or etchings by companies targeting the middle-class market, while others served as illustrations for magazines and calendars. She became especially well-known for her depictions of the domestic life of George and Martha Washington, painting a number of scenes of social events at Mount Vernon.

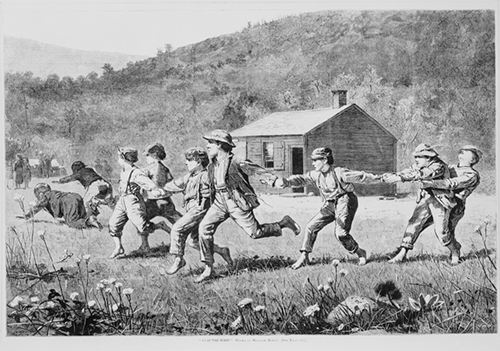

This painting, which was published as an etching by New Jersey printmaker James S. King, exemplifies Brownscombe’s mature style, which combines her academic training with the naturalism favored by painters on both sides of the Atlantic, including the American Winslow Homer and the Frenchman Jean-François Millet. The picture depicts a scene from Brownscombe’s time, as indicated by the nineteenth century hairstyles (particularly the men’s facial hair), but draws upon Brownscombe interest in and careful study of Rococo and other historical architecture in France, Germany, and Italy. The depiction of the choir boys—sweetly orderly but also individualized—shows Brownscombe’s attention to popular sentimental taste.

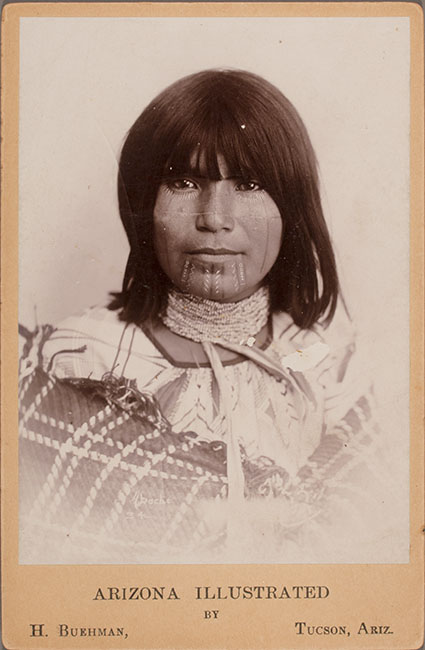

Henry Buehman

(American, b. Germany, 1851-1912)Tattooed Woman, Photograph

6 1/2 x 4 1/4 in.

The Alfond Collection of Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2017.15.15 Image courtesy of the artist

German-born American photographer Henry Buehman emigrated to the United States in 1868 with three years of photography experience. He worked as an itinerant photographer in places like California, Nevada, and Utah before settling in Tucson, Arizona, where he established his own photography studio. Buehman’s trips around surrounding Arizona territory allowed him to add scenic images and portraits of Native Americans to his portfolio. Although the identity of the woman in this image is unknown, her facial tattoos suggest she is possibly part of the Apache tribe. She is pictured wearing a beaded necklace; the white lines and circles in her vertical chin tattoos are painted in by the photographer. Bushman's portraits allow viewers to have a glance of the Western United States and Native American culture during a period much different from current times.

James Buttersworth

(American, b. England, 1817-1894)Black Squall at Gibraltar, ca. 1855

Oil on artist’s board

15 x 23 ½ inches

Donated in memory of Robert G. Scully. 2019.10

James Edward Buttersworth was born in London, where he was trained by his father Thomas, himself a successful painter of maritime scenes. Buttersworth emigrated to the United States sometime between by 1847, after a successful early career in England. Settling in Lower Manhattan, followed by Hoboken, New Jersey, Buttersworth quickly established himself as one of the foremost marine painters in the country. The 1850s were a particularly auspicious time for American marine painting, due to recent advances in maritime technology. The clipper ships—invented for the tea trade with China—became even more important after the discovery of gold in California, setting off a race to build the fastest possible ship. Similarly, American success in sailing races set off a mania for yachting. The owners of these vessels and the public alike clamored for accurate depictions of them, and Buttersworth tapped into this burgeoning market.

Buttersworth became one of the country’s foremost painters of daring maritime scenes, known for his ability to accurately represent details of rigging and other aspects of shipboard architecture—a skill which was highly prized by collectors—combined with the drama and adventure of the high seas. In this scene, which takes place just off the Rock of Gibraltar at the entrance to the Mediterranean Sea. In the background, British ships at anchor are tossed by the storm, which all but blots out the light of day. The foreground ship, identifiable as a clipper by its raked-back elegance and prominent bow, desperately attempts to furl sail in the face of the onslaught. Capturing the moment of highest drama, Buttersworth punctuates the danger with jagged stripes of lightning that jut out into the inky blackness.

Emil Carlsen

(American, 1853-1932)Still Life with Copper Pot, ca. 1910

Oil on Canvas

6 ¼ x 5 ⅛ in

The Alfond Collection of Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara ‘68 and Theodore ‘68 Alfond. 2023.30

Born in Denmark, Emil Carlsen immigrated to Chicago in 1872, where he trained under a fellow Danish painter named Lauritz Holst. When Holst returned to Denmark, Carlsen inherited his studio, also becoming an instructor at the Chicago Academy of Design. In 1875 Carlsen traveled to Paris, where he became interested in the soft, delicate realism of the French still-life painter Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin. He moved to New York in 1879. Struggling to make ends meet as a painter, he lived a semi-peripatetic existence that saw him move to Philadelphia; back to Europe; to San Francisco; and finally back to New York by 1891. In 1896, at the age of 50, he married, moving with his wife into his studio on 59th street. After this, both his personal and professional lives became much more settled, and he embarked on a career as a teacher at the National Academy of Design, Art Students League, and Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

During this time Carlsen also became friends with John Henry Twachtman, Julian Alden Weir, and other painters affiliated with the Tonalist movement in landscape painting. Twachtman, Weir, and the Tonalists inaugurated a quieter and more intimate mode of landscape painting, in contrast to the bombast that characterized the Hudson River School of earlier generations. Carlsen’s interest in quietly intimate still-life painting meshed well with the Tonalist aesthetic. This painting is a prime example of this style, the popularity of which finally ensured Carlsen’s financial stability. He represents the copper urn and humble onions with a graceful sensitivity, emphasizing the effects of light and texture over strict illusionism.

Jean Charlot

(American, b. Paris, France, 1898-1979)A woman standing with a child on her back, 1933

Color lithograph

16 x 10 7/8 in.

Gift of Charles and Julie Day Pinney, 2017.11.1 © Jean Charlot/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Over his long and productive career Jean Charlot had a profound influence on printmaking and mural painting in both Mexico and the United States. He was born in Paris and in 1921 moved to Mexico City after the death of his father—his mother was of mixed French and Aztec ancestry, a fact in which the family took great pride. He arrived at an auspicious time in Mexican history, as the period of unrest and social change surrounding the Mexican Revolution was beginning to wind down. When he arrived, he joined a ferment of artistic and cultural experimentation—known as Mexican modernism—that was answering the urgent question of what it meant to be Mexican. Charlot, who brought with him printmaking knowledge and equipment, as well as examples of modernist prints from France, is often credited with helping to inspire a revolution in printmaking in Mexico.

Charlot joined SOPTE (Sindicato de los Obreros Técnicos, Pintores y Excultores), an artist’s union, and signed on to their 1922 “Declaration of Social, Political, and Aesthetic Principles,” written by David Alfaro Siqueiros, whose large fresco murals are icons of Mexican Modernism. In the Declaration, the artists condemned easel painting as overly aristocratic and intellectual, preferring instead the more direct and accessible mediums of murals and printmaking. Charlot also joined the movement of artists and intellectuals known as Stridentism. Influced by Italian Futurism, Spanish Ultraism, and Dada, Stridentism celebrated modern technology and artistic forms, rejecting the staid classicism of traditional European art. Unlike the Futurists, however, the Stridentists rejected war and fascism, maintaining their socialist political commitments.

Charlot moved to New York in 1929, spending time there with George C. Miller, the best fine art lithographer in the United States, to whom he was introduced by José Clemente Orozco, another of his colleagues in the Mexican modernist movement. In 1949 he went to Honolulu to do a mural commission for the University of Hawai’i. He so enjoyed his time there that he stayed until his death in 1979, executing many of his prints by correspondence with Lynton R. Kistler, a master lithographer based in Los Angeles.

Jean Charlot

(American, b. Paris, France, 1898-1979)Sunday Hat, 1947

Lithograph

17 1/4 x 12 1/2 in.

Gift of Charles and Julie Day Pinney, 2017.11.2 © Jean Charlot/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jean Charlot

(American, b. Paris, France, 1898-1979)Leopard Hunter, 1929

Lithograph

13 1/2 x 17 1/2 in.

Gift of Charles and Julie Day Pinney, 2017.11.3 © Jean Charlot/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Charlot left Mexico City for New York in 1929, making this print shortly after he arrived. It demonstrates both his approach to Mexican subjects and his continued formal and technical experimentation. Like many of his prints, it is based on careful observation of his subjects, in this case Mayan hunters in the Yucatán. Charlot wrote in his diary of watching the men leave to hunt at night, wearing lanterns on their heads to attract the leopards. His enthusiasm for Mexican culture led him to learn Nahuatl, the Aztec language, and he sought always to approach his subjects from a position of respect. The figure of the man, his back bent under the weight of the leopard, is represented with the solid monumentality he and other artists brought to Mexican modernism. The hunter’s smooth, rounded forms contrast sharply with the angular machinery of the gun. The darkness of the night sky, represented with swirling forms as well as sharper lines, shows Charlot’s interest in expanding the possibilities of lithography, a medium that traditionally was known for its clean lines and commercial uses.

Jean Charlot

(American, b. Paris, France, 1898-1979)Tortilleras, 1947

Lithograph

17 1/4 x 13 in.

Gift of Charles and Julie Day Pinney, 2017.11.5 © Jean Charlot/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jean Charlot

(American, b. Paris, France, 1898-1979)Procession at Chalma, 1947

Color lithograph

25 x 20 in.

Gift of Charles and Julie Day Pinney, 2017.11.10 © Jean Charlot/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jean Charlot

(American, b. Paris, France, 1898-1979)The Great Builders II, 1930

Lithograph

15 3/4 x 21 in.

Gift of Charles and Julie Day Pinney, 2017.11.11 © Jean Charlot/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

William Merritt Chase

(American, 1849-1916)Autumn Fruit, 1871

Oil on canvas

30 x 25 in.

Gift from the Martin Andersen-Gracia Andersen Foundation, Inc, 2022.14

William Merritt Chase was renowned during his time for his depictions of the American landscape as well as for his depictions of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century’s confident and stylish “new women.” He was perhaps most famous, however, for his still-life paintings, in particular his depictions of freshly caught cod and other North American fish. Shimmering with iridescent scales and still glistening from the sea, these fish were the perfect vehicles for Chase to showcase his masterful brushwork and rapid application of paint—he often did them as demonstration pieces in front of adoring audiences.

The fish pictures date from Chase’s mature period around the turn of the twentieth century. This one, on the other hand, dates from just before the pivotal year of 1872, when he began a six-year stint studying in Munich. After a couple years in New York, where he studied at the National Academy of Design, Chase was living in St. Louis, where he established a local reputation for his still lifes. This painting shows his early mastery of the American still-life tradition. Set in a nondescript domestic interior, the picture includes a variety of succulent fruits, as well as a glass of wine—likely Madeira, a fortified dessert wine popular in the nineteenth century—and a piece of steak or other meat, a curious addition for a painting entitled Autumn Fruit. The American still-life as formulated by Raphaelle Peale, Severin Roesen, and other earlier painters prioritized pyramidal compositions and dark backgrounds, lending the produce an air of powerful beauty. Insect-chewed leaves and spots such as those on the peaches both heighten the naturalism of the depiction and hint at the food’s perishability, reminding the viewer of the fleeting nature of material abundance. Chase has given the fruit—particularly the grapes—a highly reflective shine, a practice designed to show his mastery of optical effects. Though Chase would develop a looser style during and after his stay in Munich, this painting shows his strong grasp of the textural and optical qualities of oil paint.

William Merritt Chase

(American, 1849-1916)Young Woman With Red Flowers, 1904

Oil on canvas

24 x 17 3/4 in.

Gift of Gertrude Lundberg Richards, 1967.19

William Merritt Chase was one of the most influential artists of the turn of the twentieth century, both as a painter—he helped introduce the artistic styles of Munich and Paris to the United States—and as a teacher and patron of the arts. From his return to the United States from Munich in 1878 Chase worked as a teacher, first at the Art Students’ League and later at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, as well as in a variety of summer schools, including the famed Shinnecock School on Long Island. A key aspect of his teaching was the live demonstration, in which he executed a landscape, still-life, or portrait study while his students watched, commenting all the while on his process. These performances were showcases for his bravura painting style, which emphasized loose, painterly brush strokes and largely eschewed preparatory drawing. When he was finished with the painting he would usually give it away, either bequeathing it to the school, giving it to the student who had served as model, or raffling it off.

This painting depicts a “Miss Covert,” and is the result of one of Chase’s in-class demonstrations. The young woman’s loose dress, fashionable high collar and straightforward gaze—which unflinchingly returns the viewer’s glance—marks her as a New Woman, a frequent Chase subject. New Women rejected many of the buttoned-up gender roles of the nineteenth century, taking on traditionally masculine roles, including that of artist. Chase was an early champion of female art students, remarking that genius knew no sex. At the same time, the flowers she holds serve to soften and feminize her, as well as emphasize the pink rosiness of her complexion.

William Merritt Chase

(American, 1849-1916)Spanish Peasant, ca. 1881

Intaglio print

4 3/4 in. x 2 3/8 in.

Gift of Mrs. Fred Perry Powers 1978.25.1

William Merritt Chase

(American, 1849-1916)Keying Up-the Court Jester, ca. 1879

Intaglio print

5 3/4 in. x 3 1/2 in.

Gift of Mrs. Fred Perry Powers 1978.25.2

This print is a reproduction of Chase’s early masterpiece Keying Up-the Court Jester (1875, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts), which he painted in 1875 while he was studying in Munich. Depicting a local artists’ model as a merry clown, the painting was intended to help Chase achieve notice back home in the United States. At this it was very successful, receiving rave reviews at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, as well as several other important exhibitions, including the National Academy of Design. It was a showcase for Chase’s bold new style, which merged the “brown sauce” of the Munich painters with his study of the Old Masters and his bravura brushwork.

He executed this etching soon after his return to the United States, as part of a scheme to disseminate low-cost reproductions of his work to inspire further interest. Chase executed a handful of other prints, including Spanish Peasant (1978.25.1), but in general did not embrace etching with the enthusiasm of many of his contemporaries. This Is likely due in large part to his disinterest in drawing—he was overall a poor draftsman—and preference for creating his paintings directly on the canvas. This preference for freewheeling composition led to his embrace of pastels, of which he was a foremost proponent around the turn of the twentieth century. He instead turned to his outlandish and performative persona for the bulk of his marketing, soon becoming one of the most celebrated and beloved painters of his day.

Thomas Cole

(American, 1801-1848)Catskill Mountain House, The Four Elements, 1843-44

Oil on Canvas

40 x 40 ½ in.

Gift of Diane and Michael Maher. 2023.6

Thomas Cole was born in the industrial northwest of England, where his early experiences included both artistic and vocational training, specifically as an apprentice textile engraver. He immigrated to the United States with his family at the age of seventeen, eventually finding work as an engraver. He taught himself to paint, launching a career as a landscape artist over his father’s strenuous objections. His early exposure to European–particularly English–artistic traditions situated him perfectly to take advantage of his new home, and he began making sketching trips to the Catskills and other mountainous areas of the American Northeast. He capitalized on early successes to become the exemplar of a new, American school of landscape painting, quickly becoming known for both allegorical sequences such as The Voyage of Life (National Gallery of Art, Washington) and scenes of specific locations such as The Oxbow (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

This painting exists in the latter mode, depicting the famed Catskill Mountain House, a hotel and tourist attraction that brought painters as well as vacationers from throughout the country. Cole, who from 1827 was a resident of the nearby village of Catskill, had a complex relationship with the Mountain House. He wrote fondly of visiting the place, and often used it as a stop in his rambling throughout the surrounding hills. At the same time, he despaired of the changes wrought by the hotel and other economic development, in particular the tanneries, mills, and other industries that rapidly overtook the area in the 1830s and 1840s. This painting is a register of his rage and despair at these changes, as the titular house is dwarfed by the awesome power of a thunderous storm. In a sense, it shows Cole attempting to reverse the ravages of time, returning his beloved Catskills to their state when he first encountered them, undoing decades of environmental degradation.

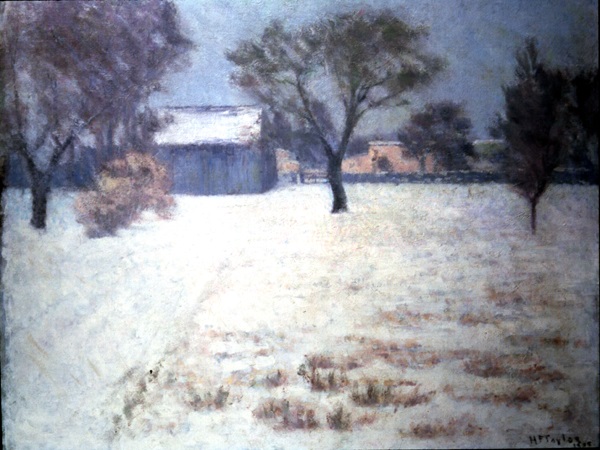

Timothy Cole

(American, b. England, 1852-1931)A Frosty Morning, 1902

Wood engraving

7 1/2 in. x 10 3/8 in. print

Gift of George H. Sullivan, 1957.107

Born in England, Timothy Cole immigrated to the United States when he was five, apprenticing in the shop of a company that made wood-engraved diagrams of machinery. Wood engraving, which was invented by Englishman Thomas Bewick at the end of the eighteenth century, involves using an engraver’s tool—called a burin—to make an image on the tough end grain of a piece of wood. The result, which combines the durability of woodcut with the precision of copperplate engraving, was the preferred method for reproductive printmaking in the nineteenth century, especially because the wood blocks could be made at type height for easy incorporation into magazine, newspaper, and book printing.

Cole eventually found his way to The Century Magazine, which sent him to Europe to make engravings of masterpieces of European painting, thereby bringing them to readers who would otherwise have no opportunity to go themselves. A Frosty Morning is one such work, based on an 1813 painting of the same title by Joseoph Mallord William Turner, now at the Tate, and demonstrates Cole’s mastery of the medium. His innovative working method involved coating his wood plate with photographic emulsion so that he could print an image of the painting he was copying directly on the surface. Then, he sat in the gallery and worked, looking at the painting in a mirror, to match the effect of the photographic reversal. Using incredibly fine burins, he was able to achieve stunning effects of tone, carefully removing tiny amounts of wood to create the white spaces in the composition. The process was so time-consuming that Cole was able to produce only one or two such images a year.

Paul Cornoyer

(American, 1864-1923)Madison Square Park, New York, ca. 1905-1910

Oil on Canvas

16 x 22 in.

Intended Gift from the Martin Andersen – Gracia Andersen Foundation, Inc. 2022.15.LTL

Born in St. Louis, Paul Cornoyer studied at the St. Louis School of Art from the age of 17 while he saved up to study in Paris. In 1889, when he was 25, he was finally able to embark on a multiyear trip to the French capital, enrolling at the Academie Julian and studying in the studios of French masters including Jules Lefebrve, Louis Blanc, and Benjamin Constant. Returning to St. Louis, he quickly moved to the top of the local art scene, winning prizes and commissions. One of his paintings, which he entered in an exhibition in Philadelphia, came to the attention of William Merritt Chase, himself briefly a St. Louis resident early in his career. Chase urged Cornoyer to move to New York, which he quickly did. There he established himself amid the group of artists—including John Henry Twachtman, J. Alden Weir, Thomas Wilmer Dewing, and Childe Hassam—who are variously known as Tonalists and American Impressionists.

Like many artists of his generation, Cornoyer spent his summers on the shore, in his case in Gloucester, Massachusetts. It was his depictions of New York, however, which brought him the most notice. Like the Impressionists, whose work he had encountered during his time in Paris, Cornoyer was interested in the effects of light and atmosphere in a single place during different times of day, weather conditions, and seasons. His New York scenes thus mostly focus on a few places, most notably parks. He made rainy scenes something of a specialty, becoming especially praised for his depiction of wet pavement. In this painting, an excellent example of his depictions of rainy New York, the sky seems to lighten as the rain peters out, while the shimmering reflections of pedestrians and carriages on the ground indicate that it has until recently been raining quite heavily.

Roy Crane

(American, 1901-1977)Untitled (Lookout), 1937

Pen and ink

5 ½ in by 21 5/8 in

Gift of the Artist, 1978.23.5

hese two comic strips are the work of Roy Crane, one of the pioneers of the adventure strip genre that dominated American newspapers in the middle of the twentieth century. The strips, which date from ten years apart, are both daily entries from his first successful strip, Wash Tubbs. The story of the eponymous hero—short for Washington Tubbs II—Wash Tubbs saw its protagonist ranging all over the world visiting exotic places both real and fictional. Wherever he went, Wash—the worried-looking figure with curly hair in the first panel of Untitled (Lookout)—sought both his fortune and the love of a local beauty, though he rarely succeeded in either pursuit.

In addition to formulating the conventions of the adventure strip genre, Crane was an innovator in his mixture of cartoonish characters and realistic backgrounds. He used Craftint doubletone illustration board, a chemically treated type of paper that allowed him to achieve a wide range of gray tones and fine details, to evoke whatever exotic land Wash was visiting that week. The strips—in particular Untitled (Infatuation), in which Wash is visiting Mexico—are also artifacts of their time, reproducing the class and ethnic assumptions of Crane’s American audience.

Roy Crane

(American, 1901-1977)Untitled (Infatuation), 1947

Pen and ink

5 ½ in by 22 1/8 in

Unknown source, 1978.23.6

Ralston Crawford

(American, 1906-1978)Havana Harbor #3, 1948

Oil on Canvas

36 1/4 x 30 21/64 in. (92.08 x 77.03 cm)

The Alfond Collection of Art at Rollins College, Gift of Barbara ‘68 and Theodore ‘68 Alfond, 2017.15.2

Ralston Crawford first came to prominence in the 1930s for his sharply linear depictions of American industry, an interest that aligned him with the Precisionist movement. His depictions of grain elevators, factories, and modern highways were informed by his study of French modernism, in particular Cubism, lending his work a flat, partially abstract aspect. Unlike many of his colleagues, Crawford refused to avoid service during World War II, and was assigned to the Visual Presentation Unit, Weather, of the Army Air Force, where he used his modernist style to streamline the presentation of weather data to the high command in Washington, D.C. After the war he was the only artist present at the nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll. His experience of military life and the atom bomb deeply unsettled him, inaugurating a less optimistic and more abstract style that he maintained until the end of his life.

This painting dates from this later period, when Crawford traveled frequently, supplementing his income as an artist with temporary teaching positions and illustration work for magazines such as Life and Fortune. One of a series depicting Havana Harbor, the flat planes of color and slashing lines evoke a feeling, rather than depicting a specific place. Crawford’s late career work demonstrates his increasing interest in the interplay and tension between order, chaos, and destruction, a dynamic which is enhanced by the spare palette and sharp angles of this painting. Crawford was a steadily successful artist from the 1940s onward, but he attracted little critical attention, largely because his Cubist-derived geometry fell increasingly out of fashion as the Surrealist-inflect Abstract Expressionist movement came to dominate American art.

Edward Sheriff Curtis

(American, 1868–1952)Shield Oglala, 1907

Photogravure

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. J. William Loving Jr., 2013.31

Born in rural Wisconsin to an impoverished itinerant preacher, Edward S. Curtis eventually ended up in Seattle, Washington, where he became the co-proprietor of a portrait photography business. He soon discovered a passion and aptitude for the medium. A chance encounter led him to be invited on the 1899 expedition to Alaska sponsored by railroad magnate Edward H. Harriman alongside a number of prominent anthropologists and scientists. Though he had previously made portraits of local Native Americans, it was on the Harriman Expedition that Curtis discovered his interest in ethnographic photography, eventually leading to his decision to create his forty-volume opus The American Indian. Consisting of over 2200 photogravure images and over 5000 pages of text, the project took decades to complete, even with the financial and publicity support of such luminaries as President Theodore Roosevelt and J.P. Morgan.

This image was taken in 1907, early in the project’s history, and appears in the third volume. It shows Curtis’s signature blending of Pictorialist art photography and supposedly scientific ethnographic imagery. Shield, like many of Curtis’s sitters, is shown wearing a traditional costume and hairstyle. Curtis, like many of his contemporaries, was a believer in the “vanishing race,” the notion that American Indians represented an ancient, static culture that was destined to disappear from the world. By representing his sitters in traditional costumes, Curtis helped to advance this hypothesis while also playing into contemporary expectations of what Native people looked like. At the same time, however, Curtis uses the hazy, soft focus that was characteristic of fine art photography at the time. Shield’s downturned, careworn face indicates that Curtis also sought to represent his sitters as individuals. Both of these factors undermine the photo’s ethnographic intent. His photos’ beauty also caused a revival in regard for Curtis’s work starting around 1970, when his work became increasingly appreciated for its poetic beauty.

Norman Daly

(American, 1911-2008)Bull and Cow, 1949

Oil on Canvas

28 x 36 in.

Gift of David Daly, 2022.11 © 2022 Estate of Norman Daly

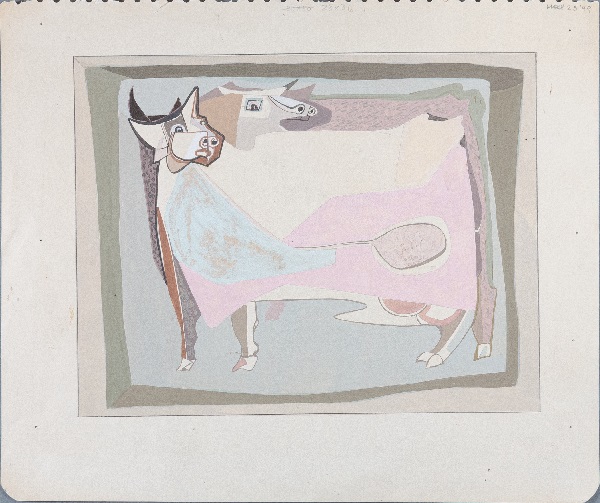

Norman Daly

(American, 1911-2008)Study for Bull and Cow, 1949

Gouache

7 x 9 in.

Gift of David Daly, 2022.12 ©2022 Estate of Norman Daly

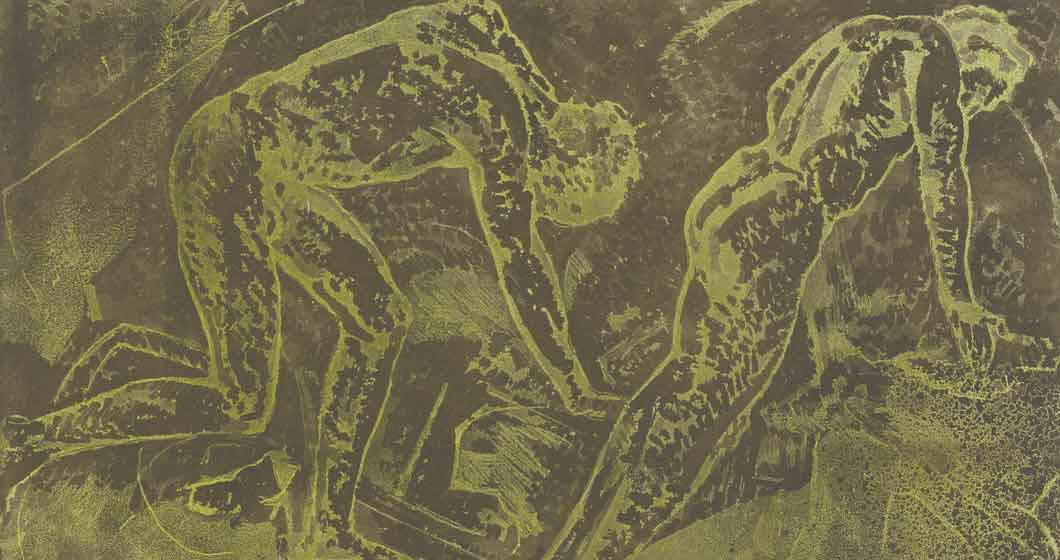

Arthur B. Davies

(American, 1862–1928)Uprising, 1919

Soft ground and aquatint

9 1/4 in. x 12 in.

Bequest of Virginia Keep Clark, 1961.8

The Rollins Museum of Art is home to a particularly fine collection of paintings, drawings, and prints by the American artist Arthur Bowen Davies. Davies was instrumental to the development of modern art in the United States, serving as the primary organizer of the International Exhibition of Modern Art, commonly known as the Armory Show. Through it, Americans got their first taste of European modern art, including works by Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, and other important members of the avant-garde. Davies, who mostly lived a secretive, buttoned-up life, was hailed for his almost instinctual understanding of modernism, even as he ruffled feathers with his near-dictatorial control of the exhibition.

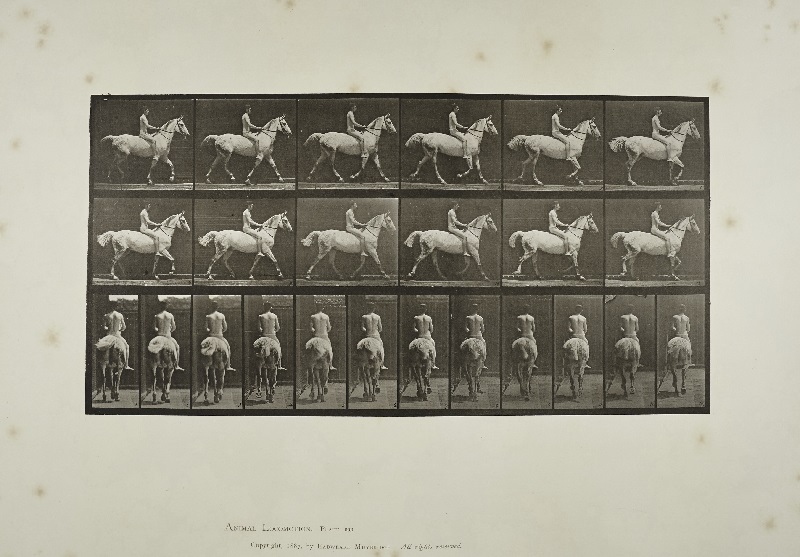

The gift of Virginia Keep Clark, herself an artist and illustrator as well as a friend of Davies, the collection represents the full breadth of his artistic production, which included landscape as well as figurative painting. Davies specialized in depictions of nudes in landscapes, often the same figure repeated in slight variations of the same position. Davies referred to these multiple figures as examples of “continuous composition.” They were inspired by his study of the photographic motion studies of Eadweard Muybridge, the paintings of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, and ancient—particularly Greek—art. This lithograph is one such example, showing the same muscular figure at two different points in the process of lifting himself up by his arms.

Arthur Bowen Davies

(American, 1862-1928)Untitled Landscape, Oil on panel

5 1/8 in. x 9 7/8 in. painting

Gift of Mrs. Virginia Keep Clark, 1961.9

Davies was originally influenced by the luminous Romanticism of the American painter Albert Pinkham Ryder and the French Symbolists. Like Ryder, he often failed to clearly name or date his canvases, and he frequently returned to them, reworking them over the course of years or even decades. This untitled and undated painting is one such example and could date any time from the 1890s to 1920s. Davies is known to have taken at least one trip to the Rocky Mountains and was also fond of mountains he saw in Italy during his frequent travels there. Regardless of the source material, this small, luminous painting is a prime example of Davies’s landscape style. Thinly painted bands of blue denote foothills, mountain, and sky, with bits of the wood panel on which it is painted peeking through, giving the whole scene a cool, otherworldly quality. The effect is one of a personal—and deeply spiritual—experience of the landscape, rather than an attempt to render objective reality.

Arthur Bowen Davies

(American, 1862-1928)Entreat, 1927

1926 Mezzotint, only state

9 7/8 in. x 6 3/4 in. print

Virginia Keep Clark, 1961.10

Arthur B. Davies was known in his own time as a rigid and secretive man who rarely allowed visitors to his studio, a practice which he claimed allowed him to focus on his work. Only a few of his closest friends knew the truth, which was the secrecy was designed to deflect attention from his scandalous personal life. Davies was officially married to Virginia Meriweather Davies, one of the first female physicians in New York State, but also maintained a second household in the city with Edna Potter, a ballet dancer who had been one of his models. Upon his death his wife destroyed much of his correspondence and other archives, likely due to a combination of anger and a desire to protect her family’s reputation. This lack of an archive has sometimes frustrated scholars’ ability to date his work and otherwise construct a chronology of his life.

For many years Davies’s art was overshadowed by this scandal and his contributions to the Armory Show, but in recent years scholars have begun to explore his engagement with contemporary cultural practices. In particular, Davies was interested in body postures, which he encountered through a blend of theosophy and other new spiritual movements, modern dance, ancient Greek art, and his own practice of breathing exercises designed to control his angina. Of particular interest was what he called the “lift of inhalation,” which he believed gave art its spiritual power. This mezzotint is a prime example of a common theme in his art, which is the depiction of nude women at the moment of maximum expansion of the chest. The model’s athletic arms and active posture help to achieve Davies’s desired feeling of mythic and timeless spirituality.

Arthur Bowen Davies

(American, 1862-1928)Tree and Figure, Lithograph, gouache

15 in. x 11 in. painting

Virginia Keep Clark, 1961.11

Arthur Bowen Davies

(American, 1862-1928)Kneeling Nude, ca. 1920s

Charcoal, pastel, paint

15 in. x 11 in. drawing

Virginia Keep Clark, 1961.12

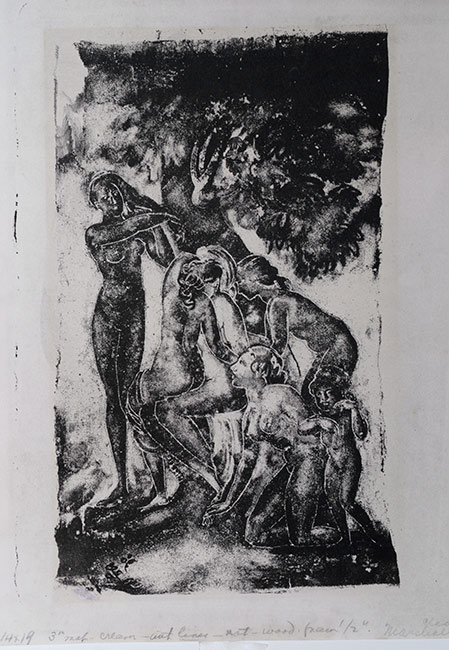

Arthur B. Davies

(American, 1862–1928)Figures of Earth, 1920

Lithograph

7 x 9 3/4 in.

Bequest of Virginia Keep Clark, 1969.13

Arthur Bowen Davies

(American, 1862-1928)Christmas Day, 1919

Lithograph

9 1/2 in. x 12 3/4 in. print

Virginia Keep Clark, 1961.14

In addition to his interest in physical and body cultures, Davies’s art demonstrated a longtime interest in dreams and the unconscious. The turn of the twentieth century saw an increase of interest in dreams, prompted by a widespread belief in the link between dreams and creativity, as well as explorations of the occult and psychic phenomena in the first decade of the century. The interest in dreams was accelerated after 1909, when Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung toured the United States, touching off a mania for psychoanalysis. This lithograph depicts a nude woman sitting on the back of a donkey, which joins a pair of goats in languidly browsing at some nearby shrubs. Birds flit about, landing on and near the woman, whose tilted head and elongated neck suggest an extended reverie. The soft, sketchy use of line and shading furthers the unreal effect, suggesting a return to a mythological, Arcadian dreamworld.

Arthur Bowen Davies

(American, 1862-1928)Landscape, Watercolor

7 1/2 in. x 11 in. painting

Virginia Keep Clark, 1961.15

Arthur Bowen Davies

(American, 1862-1928)To Virginia with Christmas Greeting , 1921

Watercolor

11 x 8 1/2 inches framed

Marshall Clark, 1962.18

Arthur B. Davies

(American, 1862-1928)Dweller On the Threshold, ca. 1915

Oil on canvas

17 x 21 3/4 in.

Bequest of Virginia Keep Clark, 1962.17

F. Holland Day

(American, 1864–1933)Ziletta, 1895

Photogravure print

Purchased with the Michel Roux Acquisitions Fund, 2013.12