What It’s Like ... to Uncover Ancient Secrets in Your Own Backyard

November 09, 2021

By Zoe Milburn ’22 and Ellie Minette ’22, as told to Stephanie Rizzo

Get an inside look at the history of Shell Island through the eyes of anthropology majors Zoe Milburn ’22 and Ellie Minette ’22, who have spent the past three years cataloging thousands of pre-Columbian items as part of an ambitious research project.

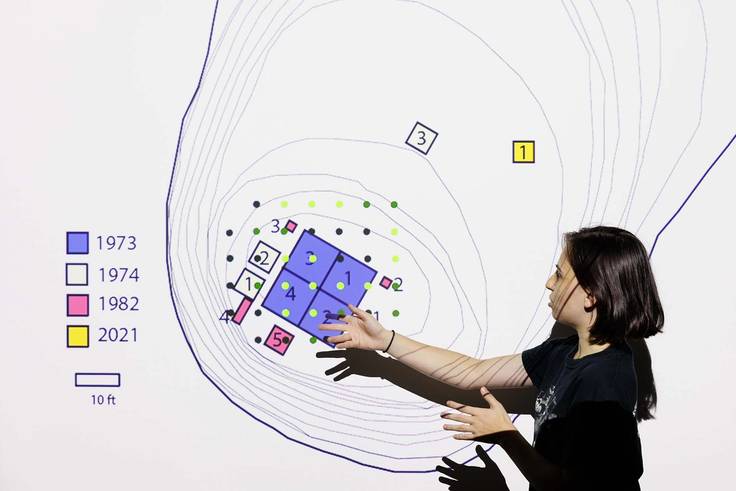

Shell Island is a small inholding located in the Wekiva Springs State Park just 20 minutes east of campus. The island has a long and storied history with Rollins. Over the past century, it’s been used as a retreat, an outdoor classroom, and—in the 1970s and ’80s after the College purchased it—as an archaeological site. Multiple excavations yielded thousands of individual artifacts, which were left unstudied in the Rollins College Archaeology Lab for almost 50 years. That is until anthropology majors Zoe Milburn ’22 and Ellie Minette ’22 teamed up with anthropology professor Zack Gilmore to begin painstakingly cataloging each item.

The inquisitive duo reflects on the three-year process of discovery and how this invaluable opportunity to learn from experience has set them up for success.

Ellie

Zoe and I got started in the lab at the end of our first year at Rollins. We both took part in the Maymester archaeological field study course that Dr. Gilmore teaches every year where we conducted an actual excavation at Shell Island. This was in May 2019, and it feels like forever ago. We enjoyed that experience so much that we both volunteered to work in the archaeology lab that fall as a way to gain even more hands-on experience.

The lab is first and foremost a classroom, and Zoe and I were both familiar with the space because we’d had classes here. There are glass cabinets that hold some artifacts, but what most people don’t realize is that the majority of Rollins’ collection is kept outside in storage. I’ll never forget walking into the hallway where the collection was kept. It smells like your grandmother’s attic, or maybe an old book. There were massive amounts of boxes—around 200 in all—filled with artifacts collected during digs in the ’70s and ’80s.

Zoe

We worked in the lab all fall, and then Dr. Gilmore presented the opportunity of working over the summer through Rollins’ Student-Faculty Collaborative Scholarship Program. We wanted to focus our research specifically on cataloging the Shell Island artifacts. As we were working on our research proposal, we were sent home due to the pandemic. We had to push our summer research back a year, but it actually worked out. We had an entire school year to work through those 200 bags of artifacts and get everything cataloged so that in the summer we were free to focus on our own dig.

Ellie

We combed through and cataloged more than 263 pounds of artifacts. That’s over 11,000 individual objects that had to be counted, weighed, and logged, plus an additional 93 pounds of vertebrate fauna that is counted separately. So it’s a massive collection that is really special to Rollins. But it was in total disarray. You’d open a box that was supposed to have four bags of artifacts inside and find eight bags.

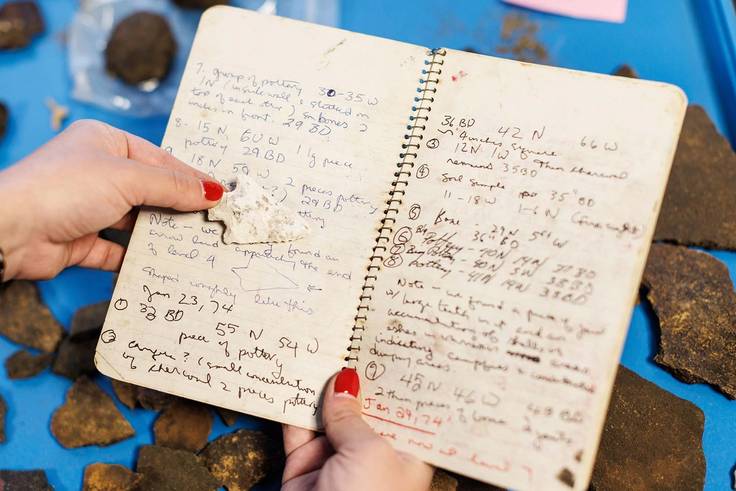

The field notes we have are 40 years old and not very comprehensive—although they contained some fun stories that gave us a glimpse into the lives of the students who completed digs in 1973, 1974, and 1982. Things like, ‘this person wasn’t working at all today, she just sat and watched the river’ or ‘so-and-so is terrible at canoeing.’ One person got accidentally hit in the head with a shovel during a dig. But while those anecdotes were entertaining, there wasn’t much in the way of useful information.

A big part of my research was focused on cataloging those earlier expeditions. Today, the standard is to dig test units meter by meter in 10-centimeter levels. Back then, they dug whatever they wanted however deep they wanted. So we really had to piece together what little notes there were with the artifacts. But we were also able to make some rather stunning discoveries.

Zoe

For instance, we found a bowl that’s made from a type of rock called soapstone. The closest source of soapstone is in the Southern Appalachian Mountains, and we were able to date the bowl to being around 3,000 years old. So we know that the people living in this part of Central Florida 3,000 years ago were engaged in trade with people living as far away as what is now South Carolina.

My research focused more on the cultural history provided by the existing artifact collection and anything yielded from the excavation. We found that there are five distinct cultural periods represented by the collection of artifacts, which span from the Seminole cultural period back to the Mount Taylor period (a pre-ceramic archaeological culture dating from approximately 5000 BCE to 2000 BCE). Based on those findings, we can conclude that Shell Island has been continually inhabited for at least 6,000 years prior to European contact and in the years after. So this collection reveals a lot about the history of the island and the people who lived there.

As summer 2021 neared, we began to once again plan our own expedition and dig to be conducted through the Student-Faculty Collaborative Scholarship Program. We decided we didn’t need to bring back a ton of stuff since the collection was already pretty extensive, but we did want to conduct a more rigorous and standardized dig in order to compare what cultural items we did find to previous findings. We also planned to dig away from the site of previous expeditions.

We settled on a one-by-one-meter square that we excavated in 10-centimeter levels. We sifted the dirt using a screen that has quarter-inch squares in it so anything bigger than a quarter-inch would remain. Using this method, we found animal bones, pottery, and stone tools. We also found marine shells, which would have had to come from the coast and therefore were probably imported.

Ellie

The whole expedition took about a week and a half. The island is only reachable by boat, so every morning we paddled out in kayaks and canoes with all of our gear. It’s about a 30-minute paddle, and after a whole day of digging, you have to paddle back against the wind, so it’s a little bit harder to do.

In addition to our research, we just finished up digitizing the entire collection. We collaborated with the Florida Public Archaeology Network (FPAN) and the Orange County Regional History Center. FPAN helped us with our fieldwork and the creation of digital models of Shell Island artifacts. The History Center has artifacts from Shell Island displayed on loan from the Rollins College Archaeology Lab. We created digital models of these artifacts, which enables us to study them in our own lab. Another cool thing about the models is that they’re publicly available and can be viewed by anyone.

We’ve also made 3-D models of some of the artifacts that you can actually print out on a 3-D printer. It was an entirely new skill I had to learn that most people might not equate with archaeology, but it has really exciting applications within the work that we do.

I’ve been working to make the print models available on Sketchfab so that scientists all over the world can print out versions of these items and study them as if they were the original artifact.

Zoe

With the conclusion of our project, we’re not just wrapping up the last three years of our lives—we’re wrapping up much more. This marks the first time in 48 years that Shell Island is not technically an active excavation site. Our plan is to present our findings to the Society for American Archaeology in the spring. From there, both Ellie and I are planning to apply for graduate programs in archaeology—forensic anthropology or biological archaeology doctoral programs for me, and public archaeology programs focused on education and public outreach for Ellie.

Ellie

I think something really cool that’s come out of this project is how much you can learn from a legacy project. Literal tons of artifacts are dug up every year, and most of them are studied for a while, and some of them are eventually put in a closet. But you can actually learn so much by going back and taking a more in-depth look at these ancient items that provide a window into the past.

See for Yourself

Get a feel for Rollins’ unique brand of engaged learning and personalized attention through one of our virtual or in-person visit experiences.

Read More

July 15, 2024

Rollins College Computer Science Professor Discusses AI and the Future of Work

Daniel Myers, an associate professor of computer science at Rollins College, provides expertise on how AI is changing the nature of work.

July 08, 2024

Gunter’s Book on Climate Change Receives Multiple Awards

Political science professor Mike Gunter’s book Climate Travels recently won awards from Foreword magazine and the American Library Association.

July 03, 2024

Rollins Welcomes Dean Lauren Smith

The 32789.com interviewed Lauren Smith, the new Dean for the Hamilton Holt School about her experience with adult education.