Farewell to our Favorite Neighbor

February 27, 2013

By Bobby Davis ’82

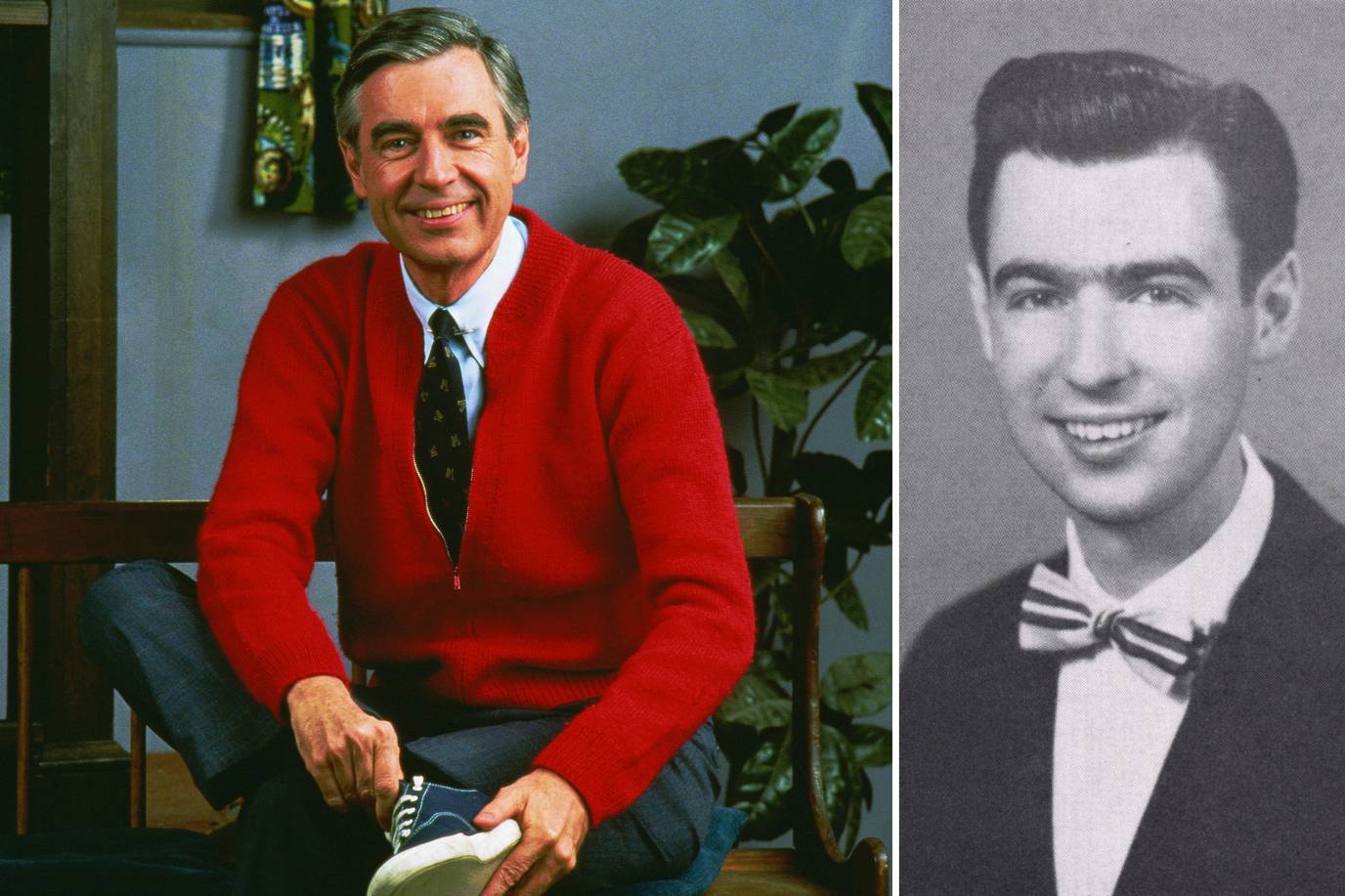

On the 10th anniversary of his death, Rollins remembers alumnus and creator of Mister Rogers Neighborhood Fred Rogers ’51.

On February 27, 2003, night closed on the Neighborhood for the last time. Fred Rogers died that day, as peacefully as he lived, a true American icon who embedded the spirit of peace and civility. Beginning in the tense early 1950s (when he developed his first television show, The Children’s Corner, in his native Pittsburgh), through the turbulent passions of the ’60s and ’70s, into the era of Hip Hop and the Internet, Fred Rogers and his Neighborhood were an oasis of calm and kindness for millions of American children and their parents. Few would complain about the television serving as a babysitter when Mister Rogers was on the job.

Fred Rogers found his calling at the dawn of the Television Age. Indeed, after graduating from Rollins with a degree in music composition, he planned to enter the seminary and become a minister—until he saw his first children’s television show in his parent’s home in 1951. Disappointed with what he saw, Rogers had an epiphany—a brilliant recognition that he could accomplish his mission to help people in an entirely new way.

“I’m a composer and piano player,” Rogers once told an interviewer, “a writer and television producer…almost by accident a performer…a husband, father, and grandfather. And I’m a minister. You know, most of us are many things, and I remember the marvelous feeling I had when I realized that many parts of who I am could be brought together in work for children and their families. That’s what I am the most: A man who cares deeply about children.”

He resolved to make television shows for children that were better than what he saw, and soon went to New York to work in the fledgling television industry. He started with NBC television as an assistant producer for The Voice of Firestone and later became floor director for The Lucky Strike Hit Parade, The Kate Smith Hour, and the NBC Opera Theatre. The medium of television was wide-open: experimental, part wasteland and part a medium for brilliant entertainment. Rogers is rarely mentioned in company of that era’s great innovators—Sid Caesar, Jackie Gleason, Lucille Ball, Steve Allen, Ernie Kovacs—yet in his way he is part of that pantheon, for he changed children’s programming forever. Along with Kukla, Fran and Ollie (which ran from 1947 to 1957), Rogers paved the way for Sesame Street, the Muppets, Barney, and the entire world of children’s educational programming, yet Mister Rogers maintained its popularity right alongside them. At its commercial peak, in 1985-86, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood drew 8 percent of American households to its friendly environs.

“When I first saw children’s television, I thought it was perfectly horrible,” Rogers once told Pittsburgh Magazine. “And I thought there was some way of using this fabulous medium to be of nurture to those who would watch and listen.”

Much changed in American family life during the 33-year run of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, yet Rogers never changed the basic format of his show. (He did, however, add many characters, including several African-American and Latino characters.) The outside world changed greatly, but the Neighborhood remained timeless. The character—Mister McFeely (named for Rogers’ adored grandfather, with whom he spent much time as a child), Lady Elaine Fairchild, King Friday XVIII, Daniel Striped Tiger, X the Owl, and others—remained his lifelong co-stars and companions. He barely seemed to age in all those years. And his message of universal respect remained as meaningful in 2001, when the show aired its last episode, as it did when it began in 1968.

The program stood out for its cast of well-realized characters, but above all for its quiet. Children were mesmerized by the tinkling of the trolley, the songs (Rogers composed more than 200 of them, including the show’s theme), the soft-spoken exchanges between Rogers and the other characters, and Rogers’ earnest discussions about things children are concerned about. Most television shows and commercials are loud and call attention to themselves, but Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood was like hanging out in your living room with your mild-mannered and loving uncle. Rogers’ signature move came at the beginning of each show, when he made himself comfortable by taking off his suit jacket and leather shoes and putting on his sweater and his sneakers, while singing, “Would you be mine, could you be mine, won’t you be my neighbor?” He subtly invited the viewer to be comfortable, and in fact Rogers said that he saw the show as an extension of his daily life, not a separate interlude.

In his three decades on the air with Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, Rogers wore more than 24 cardigan sweaters. “My mother made a sweater a month for as many years as I knew her,” Rogers said. “And every Christmas she would give this extended family of ours a sweater.

“She would say, ‘What kind do you all want next year?’ Then she’d say, ‘I know what kind you want, Freddy. You want the one with the zipper up the front.”

Despite the show’s saccharine reputation, Rogers did not close his eyes to the rise of a divorce culture or avoid difficult topics on his show. He brought a new emotional frankness to children’s programming. Children have heard—many of them for the first time—open and direct talk about divorce, conflict, adoption, religious faith, and death from kindly, comforting Mister Rogers. During the Persian Gulf War, he made a series of public-service announcements telling parents how to talk to their children about war. No wonder the Village Voice once lauded him as the only authentic father figure on television.

“I think children appreciate having a real person talk to them about feelings that are real to them. Why have two generations of children watched our programs? I’d say that’s why,” Rogers said.

Rogers was born on March 20, 1928, and grew up in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, an industrial city near Pittsburgh known for steel production, machine parts, tools, industrial ceramics, and Rolling Rock beer. He lived alone with doting parents until they adopted a daughter when he was 11, and he spent much of his time quietly, playing with puppets and making music. Even then, he and his family created an oasis of calm in a harsher environment. It is no wonder, then, that Rogers charmed the tough Rollins football players who sometimes would intimidate the Rollins music students.

“He was a very likable person, very gentle,” remembered Hap Clark ’49, one of the football players—many of whom, like Clark, were World War II veterans. “He had feelings for everybody, even the mean football players. The music students would cross the street to avoid us when we came down the street. Fred and I were joking about it last year, at our last Reunion together in March. I apologized. I said if I was ever mean to him, I was sorry. He laughed. He got a kick out of that.” Despite his “tough” image, Clark always attended Rogers’ piano recitals during their time at Rollins.

Clark noted that all three of his children grew up watching his former classmate, and he joined them as an adult. “I watched the show, sure. It was so laid back. Fred had some wonderful ideas about trying to help people live a better life,” he said.

Rogers actually spent a year at Dartmouth before transferring to Rollins, where he found a quiet, peaceful place to hone his music and intellect, while still finding time to have some fun. He studied music composition, and his studies in philosophy and religion inspired him to consider ministry. He received the Canadian French Scholarship Award and participated in numerous organizations and activities, including Alpha Phi Lambda, Chapel Staff, After Chapel Club, French Club, Student Music Guild, Chapel Choir, Bach Choir, Welcoming Committee, Intramural swimming, and Pi Kappa Lambda.

At Rollins, Rogers met his future bride, Sara Joanne Byrd Rogers ’50, a fellow music student who went on to become an accomplished concert pianist. They married in 1952 and had two children, James (born in 1959) and John (born in 1961), and they remained devoted to each other their entire lives. Joanne has been memorialized forever as Queen Sara in the Neighborhood of Make Believe.

“Before he was anyone’s icon, he was my icon,” Joanne said. “I always have seen the wisdom and quiet intelligence that’s there…It’s a kind of goodness and thoughtfulness that would have been quietly there but never known about if not for the media.”

Mary Wismar-Davis ’76 ’80MBA related her feelings about an incident that took place during a Rollins Reunion alumni concert about a decade ago. “Fred was playing the piano for a large audience of alumni when Joanne, whose flight had been delayed, walked into the room. He immediately stopped playing, jumped up, excitedly ran over, gave her a big hug and kiss, and told her how happy he was to see her. It was such a beautifully spontaneous moment of affection and love between people who had been married many years, and it didn’t matter to Fred that the room was filled with people. That’s when I truly saw that the TV Fred Rogers and the real-life Fred Rogers were one and the same.”

After graduating from Rollins, Rogers did a two-year apprenticeship in New York, then returned to Pittsburgh to help develop The Children’s Corner for a new public television station, WQED-TV, the nation’s first community-sponsored educational television station.

While developing this program, Rogers pursued his original goal and attended the Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. He was ordained a Presbyterian minister in 1963, the same year in which he moved briefly to Toronto to make his on-camera debut—a 15-minute program called Misterogers. In 1966, he returned to WQED and turned the show into the half-hour Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. The show debuted nationally in 1968 (the same year as Laugh-In, the year of assassinations and riots) on the fledgling National Education Television (NET), which became the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). The following year, it won two George Foster Peabody Awards for television excellence. The rest is history, as Rogers became one of America’s most recognized personalities and won a plethora of awards and recognitions, four Emmys among them. He has a star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame, and on New Year’s Day in 2003, in his last public appearance, he joined Bill Cosby and Art Linkletter as co-Grand Marshal of the Tournament of Roses Parade. As Pittsburgh Magazine noted, it would take 25 pages to list all the awards Rogers has won, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2002, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

Rogers, of course, would be embarrassed to see such a list. A shy man who never thought of himself as a star or celebrity, his success was merely a means to the greater end of educating and nurturing. His family, his friends, the people he worked with, knew that the gentle, decent man who appeared on television every day was the real thing. “It takes a great deal of courage to be yourself,” said Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood associate producer Hedda Sharapan. “Fred Rogers would say, ‘All I can give is my honest self.’ He was even willing to let the world see his vulnerabilities, to see when he couldn’t learn something quickly… He’s given us all more courage to be our honest selves and to appreciate our own humanness.”

A former real-life neighbor of the Rogers, Jessica Reavis, made a telling point in her commemoration for Time, saying “the most remarkable thing about Mister Rogers was not that he loved children, although that was apparent to anyone who observed him even for a moment. It’s that he respected children, not just for their ability to amuse or inspire, but for their intellect, their inherent sense of right, and their penchant for honesty.” Rogers was open-hearted enough to love children unreservedly, but he went beyond that. He was humble enough to learn from them and grant them a respect rarely accorded by adults.

Elsie Hillman, a trustee emeritus of WQED Multimedia, summed him up in this way. “Mister Rogers. What a gracious man he was. Never pretentious but always there. A teacher but never a lecturer, a man of wit and wisdom full of compassion and patience. How could anybody be so perfect? He would not want us to believe that he was perfect. He wanted to be one of us and for us to like him just that way, not to revere him. Fred Rogers made us feel good about ourselves because he seemed to understand us and to really love us. It was not a pretend, ‘in your face’ kind of love, but an in-your-heart kind of love.”

That legacy of unconditional love that is so hard for most people to give is Fred Rogers’ parting gift to his intimates, the Rollins community, and the millions of people who ever tuned in their television to listen to this unusual and remarkable man. He found his passions early in life and was able to translate them not only into a successful career, but to communicate them creatively in ways that affected the lives of people all over the world. In the midst of the Cold War, in 1987, Rogers took the extraordinary step of appearing on Russia’s longest-running children’s television program, and later welcomed that program’s host into the Neighborhood.

As a Rollins student, he was inspired by the phrase “Life is for Service” that is engraved in marble and mounted on the wall of the loggia near Strong Hall. He wrote it down on a piece of paper and carried it in his wallet throughout his life as a reminder (in later years, a framed photo of the plaque given to him by Rollins music department director John Sinclair sat on his desk). Rogers gave his life to that homily. So many of us are better for it.

“I received a package in March from Fred’s production company,” Sinclair related. “I had once shown Fred my cufflink collection, and he particularly admired one pair, so last May I gave this pair to him at his 50th wedding anniversary party in Pittsburgh. In the package I received, sent to ‘Cufflink Collector Extraordinaire,’ were the cufflinks I had given him, and written in Fred’s distinctive handwriting were the words ‘Thanks for letting me borrow these for a while.’

“Not only is it typical of the man that he would think of others during his final illness, but what a beautiful attitude. If only everyone thought of their time on earth as ‘borrowing it for a little while.’”

“Frankly, I think that after we die, we have this wide understanding of what’s real. And we’ll probably say, ‘Ah, so that’s what it was all about.’” – Fred Rogers ’51

Read More

July 15, 2024

Rollins College Computer Science Professor Discusses AI and the Future of Work

Daniel Myers, an associate professor of computer science at Rollins College, provides expertise on how AI is changing the nature of work.

July 08, 2024

Gunter’s Book on Climate Change Receives Multiple Awards

Political science professor Mike Gunter’s book Climate Travels recently won awards from Foreword magazine and the American Library Association.

July 03, 2024

Rollins Welcomes Dean Lauren Smith

The 32789.com interviewed Lauren Smith, the new Dean for the Hamilton Holt School about her experience with adult education.