Hamilton Holt and the Value of Liberal Arts Education

February 20, 2014

By Thomas McGowan

According to Rollins’ eighth president, a liberal arts education teaches students to seek truth and meaning at any age.

The economic recession has spurred skepticism and concern regarding the value of liberal arts education. These concerns are not limited to cost. Americans are asking, what’s so special about a liberal arts education? A resounding answer to this question may be found in the work of Hamilton Holt; it’s an answer that affirms the uniqueness of residential liberal arts education and underscores the enduring value of lifelong learning in liberal arts settings.

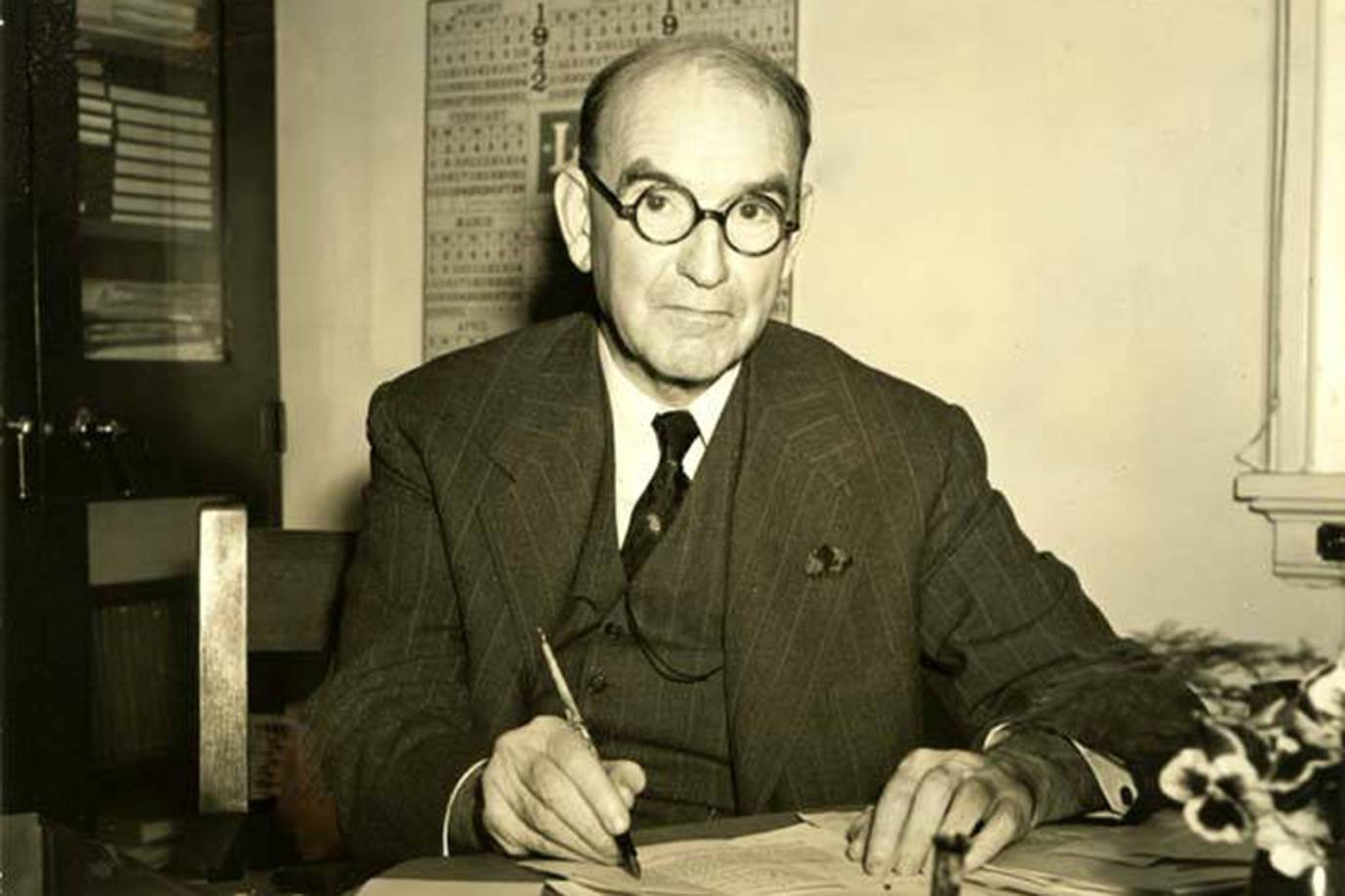

Rollins eighth president, Hamilton Holt, is the man largely responsible for building Rollins’ beautiful campus during his 24 years of service to the College (1925–49). But Holt’s legacy extends far beyond bricks and mortar; his vision of liberal arts education shaped the very soul of Rollins and directly contributed to its reputation as a national leader in innovative teaching. His vision continues to guide Rollins’ academic program and provides valuable insight into the uniqueness of liberal arts education.

Holt’s wisdom regarding the meaning and purpose of education is legendary. Students loved him and called him by his nickname, Prexy. He referred to students as his “sons and daughters” yet insisted that students never be treated as children. Holt urged everyone to “seek truth wherever it is found and follow truth wherever truth may lead.” Holt’s truth seeking led him to become a co-founder of the NAACP and an advocate for immigrants’ rights and international peace.

Hamilton Holt’s Teaching Philosophy

Holt understood that the purpose of higher education is to teach students how to become intelligent, responsible, and articulate adults; yet realizing this purpose is more challenging than it might seem. It requires an institutional culture that centers the importance of the professor-student relationship, and promotes quality professor-student interaction both within and without the classroom. Holt believed that all education is essentially self-education; the role of the professor is to model this fact to students and to cultivate appreciation for learning as a way of life. Speaking to students at his final commencement he said, “The college cannot educate you. The college can stimulate, advise, and point out the way. But the path must be trod by you.”

Within higher education, Holt believed liberal arts colleges are best suited to the task of guiding students down the path of self-education. Liberal arts colleges emphasize teaching over research and promote extensive face-to-face interaction between student and professor. This is why Holt believed that “a student goes through the university; but the college goes through the student.” The impact of a liberal arts college on the student is formative; it shapes the student’s disposition and way of being in the world.

Wisdom is insight borne from the lessons of experience; and it was from his own experience as a college student that Holt drew his insights regarding liberal education. As a Yale undergraduate and a Columbia graduate student, Holt encountered a pedagogical tradition that consisted primarily of lectures and recitations. Mono-logical and pedantic, lectures typically leave students bored and disinterested; and quizzes and recitation do little more than test the professor’s detective skills and the student’s ability to bluff.

Holt concluded that the traditional classroom experience is little more than a game in which the agency of both student and professor is displaced. Professors are denied the opportunity to teach because they are not co-present with students in an environment conducive to dialogue and informal conversation; and students are denied the opportunity to learn because they cannot interact with the professor in a relevant and meaningful way. The absurdity of this mutual displacement is most apparent during recitation when students, who are new to the material, are quizzed and questioned by the experts on the material (professors). Holt argues that this relationship should be reversed: Students should be quizzing professors, not the other way around. Inverting the relationship in this way allows students to truly learn by helping them to formulate and pose questions to the professor; the professor can then respond and assist students with the task of understanding.

Holt’s Alternative: The Conference Plan

Holt’s vision for Rollins involved a radical overhaul of the lecture and recitation model in favor of the “conference plan,” which de-centers the importance of lectures and quizzes and emphasizes the importance of teacher-student interaction in structured but informal settings. The college experience is to be organized around the principle that the most important student-learning outcome is the imprint left by the professor on the character and human development of the student. This principle is the basis of Holt’s insistence that the professor should “teach the student, not the subject.”

The role of the professor is to teach students how to learn and how to live in a manner that integrates and builds upon learning as a defining quality of one’s life. This involves mentoring students in the art of understanding, and teaching the key interpretive skills of listening, articulation, and application. The ability to formulate the right question—that is, to construct a question that clears a space for the development of understanding—is among the more important interpretive skills, and it is a skill best learned by engaging in face-to-face dialogue with professors and other students. The purpose of liberal arts education is to cultivate within the student a disposition oriented toward learning and understanding as a way of life: the student is the outcome of liberal arts education. This is why, as the Association of American College’s and Universities reports, top CEOs favor hiring liberal arts graduates; they reason well, write well, and speak coherently.

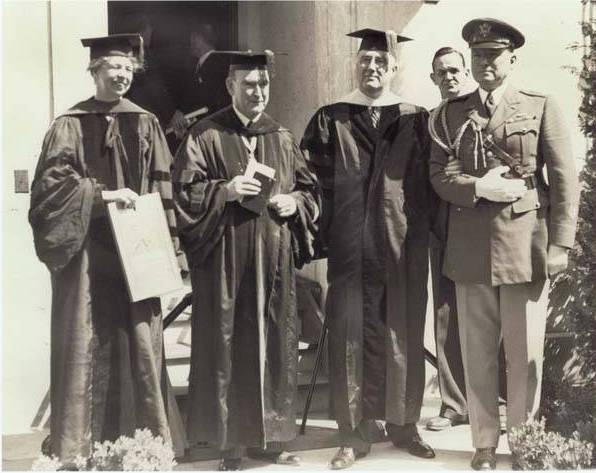

Holt’s “common sense approach” to higher education shares much with John Dewey’s pragmatic view of education. While Holt did not write about Dewey, he did host Dewey at Rollins for a national conference on the liberal arts curriculum in 1931 and shares Dewey’s appreciation for experiential learning. Like Holt, Dewey believed that the quality of the educational experience turns on the quality of teacher-student interaction. When teacher-student interaction is dialogical, that which is spoken (logos) moves through (dia) both teacher and student. This movement is especially important for the development of the student. As meaning moves through the student, it mediates the student’s self-understanding. This is because interpretation of the internalized meaning involves the mediation of implicit assumptions derived from prior experience. Dialogical interaction between teacher and student is therefore transformative and developmental.

Holt’s conference plan emphasizes the importance of dialogical experience for student development and locates it at the core of a liberal arts education. It suggests that the purpose of a liberal arts education is to cultivate a disposition toward life that seeks truth and welcomes new types of experience and knowledge. It involves a commitment to understanding the meaning of experience, even at the risk of encountering insight that results in personal change and development. An integrative disposition understands the value of enculturation, of place, of tradition; yet it also realizes that where we come from, and who we are, both enables, and constrains, who we will become. Neither capricious nor stubborn, an integrative disposition seeks understanding, values meaning, and engages the voices of others to realize one’s developmental potential. The development of this human quality is the aim of liberal education.

People engaged in lifelong learning exemplify the core quality of liberal education which Holt prized. To seek truth and meaning, at any age, is to be fully human. Lifelong learners are witnesses to the value of liberal arts education; for in their willingness to expand their understanding of self and world, we find concrete evidence of the unique value of liberal education.

It’s fitting that at Rollins, the school that bears his name, the Hamilton Holt School, is dedicated to lifelong learners and nontraditional students who engage in a liberal arts education.

Thomas G. McGowan is an associate professor of sociology and chair of the Department of Anthropology and Sociology at Rhodes College in Memphis. This article is an abridged version of the paper, “Hamilton Holt’s View of the Liberal Arts and Its Implications for Adult Education,” which was presented by McGowan during the Associated Colleges of the South’s Focus Forum on Adult Education and the Liberal Arts, held on October 11, 2013, at The Alfond Inn at Rollins.

See for Yourself

Get a feel for Rollins’ unique brand of engaged learning and personalized attention through one of our virtual or in-person visit experiences.

Read More

March 18, 2024

The Meaning of a Good Life

After attending seven colleges across three decades, Eric Reichwein ’18 discovered Rollins’ Professional Advancement programs and the quality of life he’d always wanted.

March 14, 2024

How I Advanced My Career: Eric Reichwein ’18

Find out how Eric Reichwein ’18 leveraged the personalized learning environment and top-ranked reputation of Rollins’ Professional Advancement programs to finish his bachelor’s degree and build the life and career he’s always dreamed of.

December 20, 2023

7 Reasons to Make Finishing Your Degree a New Year’s Resolution

From increasing your earnings to advancing your career, here are seven of the many reasons why finishing your bachelor’s degree should be among your New Year’s resolutions in 2024.